Cutting interest rates won’t lift inflation, it will only hurt retirees

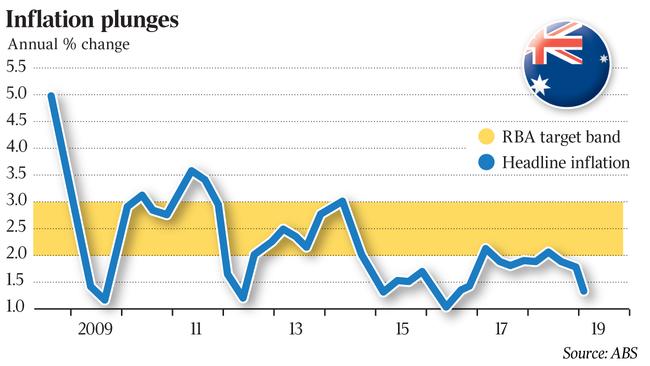

That 0.0 for the March quarter headline CPI will sit for a long time as a badge of the Reserve Bank’s impotence.

Coming up for three years of the cash rate on hold at the record low of 1.5 per cent, on top of the longest economic expansion in history, and just a week after news of another solid lift in full-time employment, inflation has fallen to zero.

So now economists are clamouring to predict a May rate cut and the headline on the story in The Australian on Wednesday went as far as predicting: “RBA could cut rates four times this year”.

As if reducing retirees’ incomes again is going to make any difference. Apart from anything else, the borrowers who theoretically benefit from a rate cut don’t reduce their repayments, so net incomes fall, not rise. Lopping another 1 per cent off interest rates might reignite the property market, and it might get the currency below US70c, but if it’s targeting the currency, the RBA is just pitting itself against commodity markets, which is not a battlefield it wants or needs to be on.

Like all central banks, the RBA would still have Milton Friedman’s picture on the wall with the quote “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, because inflation is what they target and monetary phenomena are what they do — that is, they use interest rates to move the CPI.

The rest of the economics profession has no such excuse. It’s clear to everyone outside Martin Place that monetary policy is exhausted and that this time around inflation was not killed by tight money, and therefore won’t be revived by loose money.

These days, inflation is all about power — bargaining power of workers and pricing power of companies — and not about money supply. The idea that a rate cut will somehow increase the power of either group is a fantasy.

To keep proposing rate cuts to get consumer price inflation up is now both lazy and dangerous: there is already too much debt, and encouraging more of it will only lead to higher asset prices and more speculation, leading to further disconnection between asset markets and the real world and greater income and wealth inequality.

The RBA’s target of 2-3 per cent inflation might be nice — ideal even — because it would gradually dissolve all the debt, but it rather looks like 0-1 per cent is the new normal, and maybe that’s OK. And maybe central banks should rethink their inflation targets.

Australia’s headline CPI was zero in the March quarter, and inflation is low around the developed world, because of three decades of unfettered capitalism. In fact, with the benefit of hindsight, it was the inevitable consequence of it. Capitalism produced the globalisation that allowed China to export disinflation while growing its economy 50-fold since the Tiananmen Square massacre, through the greatest, longest-lasting labour cost arbitrage in history. Now other low-cost countries are following suit as China’s labour costs rise; this will go on for decades to come.

Capitalism also achieved political supremacy around the world and disenfranchised unions in the name of battling the scourge of socialism. Socialism is dead and buried, but with it is organised labour.

And finally capitalism has financed a great flowering of technology, starting with the internet, then cloud computing and now automation and artificial intelligence, at each stage further sapping the bargaining power of labour, lowering both costs and barriers to entry.

Yes, the technology is the thing, and it is one of the great revolutions, but without venture capitalism it wouldn’t have happened.

And the only real brake on the freedom of capital these past few decades has been from competition regulators stamping out cartels and battling the misuse of market power.

Nothing wrong with that, and everything right with it, but there have been virtually no other restraints on the free operation of capitalism — only regulation designed to ensure that prices don’t go up too much, and firms don’t acquire too much power.

How could the prices of goods and services rise? Workers have lost all bargaining power through anti-union legislation, and in any case companies are reducing costs by replacing humans with cheaper and more reliable machines, and companies have lost pricing power because of cheap imports, the fragmenting of markets due to low barriers to entry and antitrust regulation.

All of that is obvious and no bad thing. Strikes and picket-lines used to be appallingly disruptive and we’re better off without them. Australia’s competition regulator, 69-year-old Rod Sims, actually works seven days a week, every week, well past retirement age even though he doesn’t need the money — he is both heroic and driven; and where would we be without our Chinese TVs and clothes, not to mention our smartphones and smart speakers to tell us what the weather is like outside.

It’s just that all of those things mean that monetary policy doesn’t work anymore and prices don’t rise. That’s fine, as long as they don’t keep cutting interest rates, and therefore savers’ incomes, to try to make prices rise.

Give up, for goodness sake, and leave rates where they are. Give retirees a break — they’ll need it with dividend franking refunds about to be abolished.

Alan Kohler is editor in chief of InvestSMART.

Don’t bother cutting rates, it’s pointless.