Coronavirus: Wages slump leaves ‘lost decade’ of young workers on their knees

Young Australians’ incomes went backwards over the 10 years to 2018, which has left this group no better off than they were in 2001.

Young Australians’ incomes went backwards over the 10 years to 2018, creating a “lost decade” of wages growth that has left them no better off than they were in 2001 and in a precarious position ahead of the COVID-19 recession.

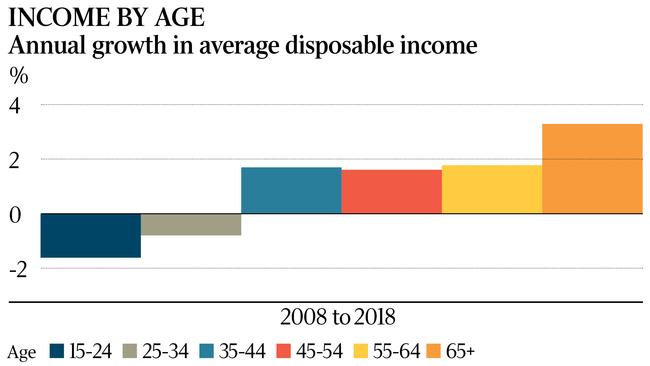

New research from the Productivity Commission shows the real (after inflation) average annual disposable income of workers aged 15 to 24 fell by 1.6 per cent between 2008 and 2018, while 25 to 34-year-olds suffered a 0.7 per cent annual decline.

The falls mean the average disposable income for 15 to 24-year-olds in 2018 was no higher than it was for the same age group in 2001. By 2018, the incomes of the 25-34 age group were only 21 per cent higher than at the start of the millennium.

By contrast, residential property prices jumped by 167 per cent between 2001 and 2018.

Productivity commissioner Catherine de Fontenay said young people had “experienced a ‘lost decade’ of income growth”.

“This means they entered the COVID-19 crisis already on lower wages, and usually with limited savings,” she said.

The PC report reveals that older Australians have fared well by comparison, particularly those aged over 65. Annual disposable income among 35 to 64-year-olds grew by 1.4 per cent over the decade, and those aged over 65 by 3.2 per cent. That left disposable incomes for the over-65s at 86 per cent higher in 2018 than in 2001, the greatest increase among the age groups.

The slow growth in wages for younger workers explained the massive difference between the age cohorts, the report says, adding that an excess of labour supply is the “most likely” explanation for stagnant and falling incomes among younger Australians.

Partly this was cyclical. A slowing economy in the wake of the GFC and the fading of the mining investment boom after 2008 reduced demand for workers, the brunt of which was borne by younger jobseekers.

But there were also structural elements. Australians are increasingly delaying retirement, meaning a greater proportion of over-55s are staying in the workforce.

A surplus of graduates has led to more young workers having to settle for jobs that fall short of their qualifications, affecting their wage outcomes and earning potential.

A shift to part-time from full-time work has also contributed to slower wage growth among young Australians. This last development was reflected in rising levels of underemployment — a measure of those working some hours but would prefer to work more.

The report reveals that immigration did not contribute to the poor income growth among young workers, as the increase in the labour force was offset by the boosted demand for goods and services from a larger population.

The findings come as the health crisis and associated economic downturn drive a spike in youth unemployment to 16.4 per cent. The Morrison government has committed $2bn to fund training initiatives to help those without work to find jobs.

“Young people face discouraging prospects in a tough job market, and there is a danger they will simply give up on their aspirations,” Ms de Fontenay said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout