Coronavirus Australia: Only 700,000 ‘directly vulnerable to layoffs’

Fewer than 700,000 people live in households ‘directly vulnerable’ to layoffs, says an economist.

Fewer than 700,000 people live in households “directly vulnerable” to layoffs, says an economist who publicly questioned the government’s bungled JobKeeper figures almost six weeks ago, fuelling concerns about the generosity of the $70bn program.

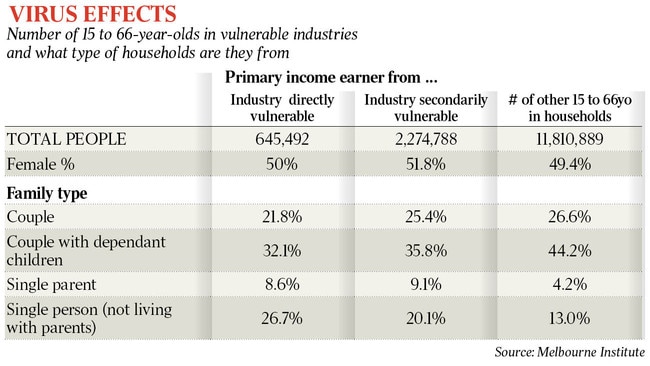

Melbourne Institute economist Roger Wilkins, who in mid-April said he “really struggled” to see how 6.5 million people could be eligible for JobKeeper, has concluded 645,000 people are living in households where the breadwinner was working in a sector directly affected by the shutdown.

“The number of people employed in directly adversely affected industries (such as hospitality, air travel and creative arts) is considerably higher than the number of people in households in which the main earner is employed in one of those industries: one million versus 645,000,” he said. “The implication is people employed in these industries are commonly not main earners in their household.”

His analysis, based on a periodic survey that tracks economic and social characteristics of 17,000 people over time, also found households most affected by the shutdown were poorer, less healthy, less skilled and more likely to be single parents or singles living alone.

“In short, those most severely impacted by the economic shutdown are also those least able to cope with it,” he said.

The analysis showed 28 per cent of the workforce, or about 3.5 million workers, were in sectors directly or secondarily affected by lockdowns, which included a disproportionate share of younger people and women, but these groups were not more likely to live in households where the breadwinner worked in one of these affected sectors.

“There’s been a lot of publicity about women being more adversely impacted but when you look at who’s in vulnerable households, it’s not really gendered in its ultimate effects on economic wellbeing,” Mr Wilkins said.

On Friday, the government admitted that three million fewer workers were eligible for JobKeeper, saving the government an estimated $60bn over the course of the six-month wage-subsidy scheme.

“I was completely mystified as to how they came up with that: more than 60 per cent of private sector workers,” he said.

“If you look at big employers for a start, you’ll find very few would have had the 50 per cent cut in revenue to qualify for the JobKeeper.”

While some Liberal backbenchers have questioned the generosity of the scheme, the government has come under pressure from welfare groups to reallocate the $60bn budget saving to include more casual workers.

Mr Wilkins’s analysis revealed the one million workers in industries directly affected by the shutdown, whose employers would be eligible for the JobKeeper payment of $750 a week per worker, had mean incomes of $654 a week.

“Despite the relatively low likelihood of workers in adversely affected industries being primary earners in their households, the number of people of working age in vulnerable households is, at 2.9 million, still very large,” he said.

People in those households were far more likely to be young, renting, in poverty and financial stress than other households. They also tended to live in urban Queensland outside of Brisbane, urban Tasmania and urban NSW outside of Sydney, with relatively fewer in Perth, the ACT or the NT.

On April 16, two weeks after JobKeeper was announced, Mr Wilkins publicly questioned the government’s estimate that 6.5 million would receive JobKeeper, costing the government $130bn over six months. “As embarrassing as this is, they would have been much more worried about underestimating by $60bn than overestimating,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout