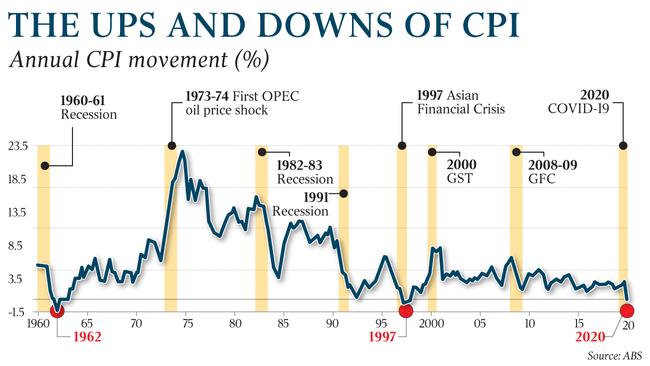

Coronavirus drives biggest fall in prices for 72 years

The biggest bout of consumer price deflation in 72 years has emerged amid the sharp economic downturn.

The biggest bout of consumer price deflation in 72 years has emerged amid the sharp economic downturn, driven by free childcare, plunging petrol prices and falling rents.

The national consumer price index dropped an unprecedented 1.9 per cent over the three months to the end of June, leaving the annual rate of inflation over the full financial year at minus 0.3 per cent.

“Since 1949, this was only the third time annual inflation has been negative. The previous times were in 1962 and 1997-98,” Australian Bureau of Statistics chief economist Bruce Hockman said in a statement on Wednesday. “This was the largest quarterly fall in the 72-year history of the CPI.”

The decline in CPI also ushered in one of the largest increases in real wages — which take into account the increase in prices — in at least a decade.

In its budget update last week the federal government forecast wages would increase 1.75 per cent over the year to June, which implies real wage growth for the year of more than 2 per cent.

Rents for residential dwellings recorded their first quarterly fall since 1972.

“The weak rental market conditions as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions and rising vacancy rates saw rents fall in most capital cities in the June quarter,” the ABS said.

Citi economist Josh Williamson said the sharp increase in unemployment had prompted significant rent relief for tenants.

“It’s also worth noting that eviction moratoriums or rent deferrals have no impact on the CPI, and job losses have concentrated in areas where this is a high proportion of renters,” he said.

Economists had expected the consumer price index, which underpins social security payments and wage negotiations, to fall in the June quarter, given state and federal government policies to make childcare and preschool free temporarily, as well as a sharp fall in global oil price.

“Excluding these three components, the CPI would have risen 0.1 per cent in the June quarter,” Mr Hockman explained.

Commonwealth Bank economist Gareth Aird said the childcare component of CPI fell 95 per cent owing to government policy that made it “free” for parents from 6th April to 28th June, and petrol prices fell 19 per cent.

“A number of the factors that pulled the headline CPI down in the second quarter will be reversed in the third quarter,” Mr Aird said.

“Childcare, for instance, is no longer free and petrol prices over July sit 7.5 per cent above their average in the second quarter.”

The Reserve Bank was expecting a weak inflation outcome, and is unlikely to change its monetary policy settings as a result.

On the RBA’s preferred measure of inflation, which excludes volatile items, prices were broadly unchanged in the June quarter, to finish the financial year 1.2 per cent higher.

Su-Lin Ong, head of strategy at RBC Capital Markets, said that inflation would remain weak far beyond the six-week second lockdown in Victoria, as rents continued to fall.

“Coupled with an unemployment rate that is set to remain well above full employment over its forecast horizon, policy will remain accommodative for the foreseeable future, with the bias towards further easing, especially if the labour market disappoints,” she added.

The federal government’s forecasts assume zero real wage growth this financial year, with both prices and wages expected to increase by 1.25 per cent.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout