Australia has a natural comparative advantage in carbon farming, just as it does in iron ore, but it is not possible to trade Australian carbon units.

In Australia, companies such as Telstra and Qantas invest on carbon farming projects to offset their emissions and the voluntary market in trading these units is estimated at $50m.

The government supports the development of carbon credits but doesn’t allow international trade in the units if they are to be used as credits against emissions created by a global company in another market.

Fidelity could invest in carbon units in Australia to offset the emissions created by its local arm, but not to offset carbon created in the US.

The more demand for Australian units, the higher the price and the greater the incentive to develop projects that reduce carbon emissions.

For a market-based government, you would think the creation of a potentially valuable new industry would be welcomed with open arms.

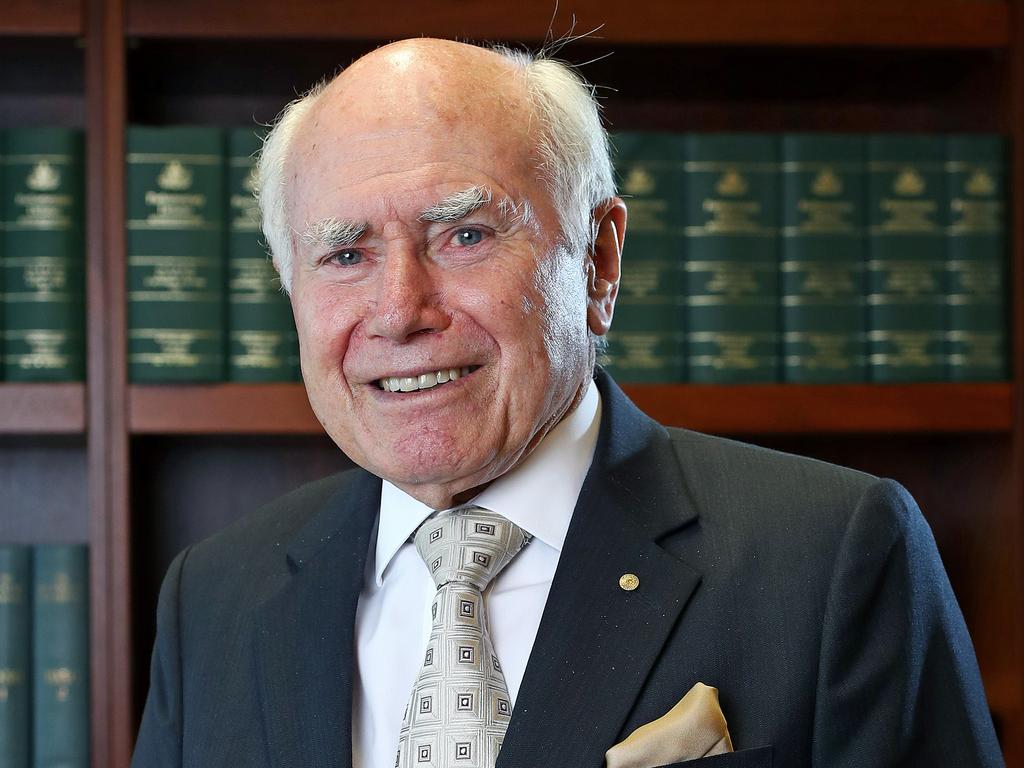

To be fair, Energy Minister Angus Taylor confided to The Australian that “Australia has one of the world’s largest and most rigorous carbon offset programs in the world and the emissions reduction fund is central to the plan to meet and beat reduction targets”.

There are now 950 registered projects, more than half under contract to the government and expected to deliver more than 200 million tonnes of carbon.

Yet in the wake of the G7 talks, the only news is around the potential for carbon tariffs on Australian goods or the latest step towards a commitment on long-term emissions.

The negatives are talked about but not the positives, which is the creation of a potential billion-dollar industry that supports Australian farmers.

What could be more positive than that?

There are international rules that govern carbon trading – known as Article 6 – and these are being negotiated amid the Paris Agreement talks.

The next trade agreement should include carbon credits to help boost the market.

The fact there is a voluntary market in Australia is not trumpeted, but the regulator has a tender that closes this week for interested parties such as the ASX or ChiX or a range of global players to make the market simpler.

It’s a long-term project, but welcomed.

It seems there is a reluctance to talk about something that creates a carbon price, but that very development is the best way to boost the market and in turn reduce Australian emissions.

Taylor is a firm believer in a voluntary market and free trade and it is high time he hit the soap box spruiking the benefits.

Next week he will address the Emissions Reduction summit run by the Carbon Markets Institute in Sydney, which would offer him the perfect opportunity to do so.

The good news is investment in renewables continues apace, with West Wind Energy developing one of the largest wind projects in the country with up to 228 turbines and 1.3 gigawatt hours of power at a cost of about $2.3bn.

The nearby Chinese-owned Goldwind Australia Stockyard Hill project is stuck in a dispute with the regulator, much to the frustration of Origin, which has a low-ball offtake agreement if the project gets moving.

West Wind’s Toby Geiger explained in an interview that wind has value because solar produces at the same time for everyone, where wind comes at other times.

Geiger notes the Golden Plains project near Ballarat is close to transmission lines, which avoids one capacity constraint on the industry and Victoria is seen as a good place to invest in wind given good government support and, with the state’s reliance on coal-fired energy, it is a good alternative.

The energy regulator noted this week that the renewables industry had its targeted 33,000 gigawatts of production.

Renewable certificates, which hit a high of $40 last year, are now trading at a spot price of $33.50 a tonne and headed lower, according to the Clean Energy Target.

With the Carbon Credit Units (CCU) heading towards $17, the fear is the falling certificate price may affect the carbon credit price, but the market fundamentals are different and should see the CCU price continuing to rise. This is important to boost project demand.

BHP’s potash move

A final investment decision is still a “few months” away, which means August or September, but BHP spent some time on Thursday explaining why it is expected to proceed with its roughly $US5.7bn ($7.5bn) potash development in Canada.

The briefing was designed to show the market fundamentals in favour of the product and cautioned final approval was with the board and would depend in part on finding the appropriate port in Canada to help get the potassium product to market.

Market talk had suggested potash leader Nutrien may want a joint venture with BHP’s Jansen mine or maybe some form of infrastructure sharing just to keep an eye on its rival.

Not surprisingly, BHP made clear on this project it doesn’t need help with the first stage of about 4.4 million tonnes at a cost of about $US115 a tonne, in a market where the average price is about $US350 a tonne. The economics are clear.

With iron ore earnings at $US20bn, potash at about $5bn is not in the same league, but key is the company is sitting on plenty of low-cost, high-grade supply and the demand outlook for food, fuel, feed and fibre was as noted almost boringly predictably good.

BHP has looked at Potash since 2006 so it’s not like it doesn’t know the market and the fact it felt the need to share with us on Thursday suggests the green light on the project that has already consumed $US3bn is all but certain. Growth options are not in abundance elsewhere.

Coles splashes out

In the few years ahead of the 2018 demerger of Coles, Wesfarmers was keeping a tight lid on its capital spending of about $500m a year, so the fact Steven Cain plans to spend $1.4bn next year on capex should come as no surprise.

Market leader Woolworths is spending $1.9bn next year, so Cain is playing catch-up after his former parent underspent, and against a rival that arguably is three-plus years ahead.

The market is worried Woolworth’s Brad Banducci is gold-plating his empire, so when Cain said spending would increase from $800m a couple of years ago to $1.4bn, supermarkets started to look almost capital-intensive.

When the business sells something weeks before having to pay for it, this is not the game investors liked, but as it transforms into a digitally based data collection vehicle that is reality and Thursday’s 4 per cent sell-off to $16.37 was overdone.

Scott Morrison has just agreed to a free-trade agreement with the UK with no mention of the inclusion of carbon credits in the equation and the question is just why.