They can have long, nasty tails, flushing out the good and bad, but ultimately they are awful times of “disruption and economic distress” as a former Reserve Bank governor once put it.

The ongoing health crisis and its global nature mean we are mired in political and economic uncertainty.

A 7 per cent fall in gross domestic product in the three months to June is a cold bucket of reality, after the March quarter national accounts showed a 0.3 per cent contraction in GDP, due to the Black Summer bushfires, border closures to foreigners and the first set of local shutdowns.

“Our record run of 28 consecutive years of economic growth has now officially come to an end,” Josh Frydenberg told reporters in Canberra’s Parliament House.

“The road ahead will be long. The road ahead will be hard. The road ahead will be bumpy.”

The Treasurer says younger people and women are being hurt by the pandemic, primarily because of the fall in employment in hospitality and retail.

As in previous downturns there will be vast structural changes, in the labour market, to spending patterns and to the shape of industry.

Businesses are zeroing-in on cutting costs, including their payrolls. So-called “zombie” firms will cease to exist when assistance measures like JobKeeper taper off and are withdrawn next year.

The least experienced workers and recent graduates will find it more difficult to grab even the bottom rung on the career ladder.

With the shift to working from home in the private and public sectors, there will be downward pressure on rents and commercial property values.

Major areas of employment, including retail and hospitality, are already under immense strain.

In the June quarter household consumption, which makes up 60 per cent of GDP, slumped by 12 per cent, the largest fall on record.

Technological and behavioural change will supercharge pandemic shifts to online shopping, home delivery of food and a flight to the regions.

Each recession has different causes but the Treasurer said the COVID-19 slump was a crisis like no other and the contraction was likely to run into the current quarter, due to the stage-four shutdown in Victoria in response to a second-wave of infections.

“The events in Victoria are expected to reduce GDP by $10 to $12bn,” Frydenberg says.

In his press conference, the Treasurer said the recession was “faster and deeper” than the ones experienced in the 1980s and 1990s.

“In those recessions, it took longer for the unemployment rate to rise as it has.

“After those recessions, it took longer than we are certainly hoping for people to get back to work.

Popping bubbles

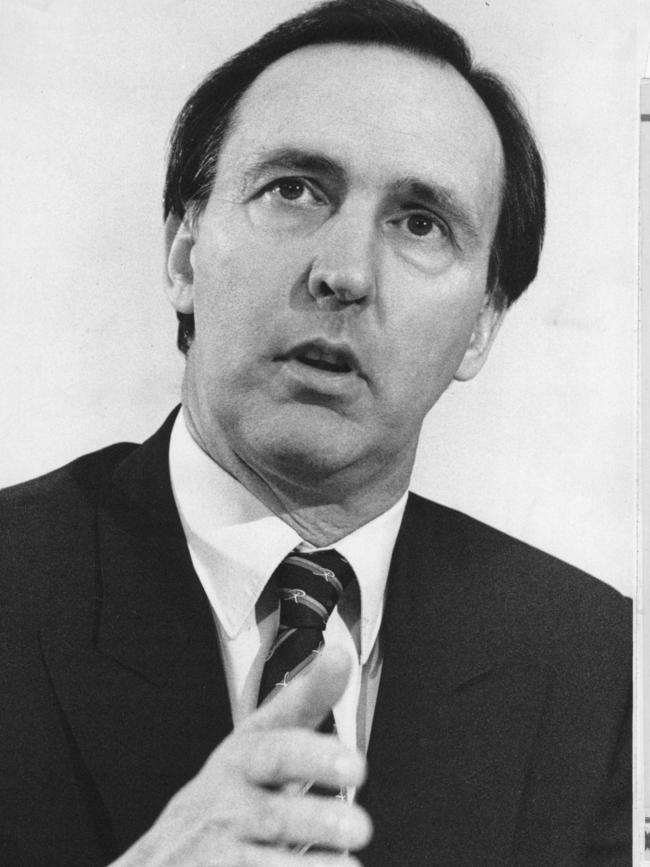

The early 1990s recession, when then treasurer Paul Keating declared it was “the recession we had to have” was induced by the RBA’s high-interest rate policy to snuff out an overheating economy, rampant borrowing and wildly inflated asset prices, everything from CBD office blocks to housing and taxi plates.

The central bank pushed the cash rate to 18 per cent.

As former RBA governor Ian Macfarlane has noted the bursting of the asset bubble was spectacular.

“Between their peak in 1989 and their trough in 1993, the average price of office buildings halved,” he said in his 2006 Boyer Lectures.

Some 17 years later, the price of office blocks was 15 per cent below its peak.

The social and economic fallout was substantial and long lasting, especially for older male workers in blue-collar jobs, working in industries like manufacturing and utilities that were also undergoing restructuring due to changes in policy.

The number of people on welfare benefits, such as the disability support pension and the dole rose steadily throughout the 90s. Income inequality rose.

Keating actually jumped the gun in using the “R-word” in November 1990, after GDP fell by 1.6 per cent in the September quarter, following a 0.9 per cent drop in the June quarter. Revisions by the statistician would scrub the June contraction, with the two consecutive negative quarters coming in March and June the following year.

That recession was particularly severe in Victoria, given its industrial profile and the financial failures of the State Bank and Pyramid Building Society.

Victorian employment fell by 8.5 per cent compared with a fall of 2.1 per cent for the rest of Australia.

On the usual measures of a drop in GDP, the 1982 recession was deeper, but as Macfarlane noted the 1991 recession was comparable to the 1961 credit crunch and oil shock of 1974.

In the COVID recession, the headline unemployment rate is expected to peak at around 10 per cent. Women and young people have felt the brunt of job losses.

Years to come back

But it will take years to get back to where we were pre-crisis in the labour market.

According to Treasury, the recession of the early 1990s, it took around seven years for the unemployment rate to fall from its peak of 11.2 per cent in 1992 to below 7 per cent.

“In addition, there may be longer-term impacts on the labour market if some workers who have been dislocated, especially those in more vulnerable cohorts, lose skills or need to re-skill to enter employment in a different occupation or industry,” Treasury noted in the July Economic and Fiscal Update.

But there can be silver linings in the misery of recession, as capital and labour shift to more productive, high-value activities.

The legacy of the previous recession according to Macfarlane and many others, was Australia once again became a low-inflation country.

“Inflation fell to around 2 per cent, which meant that for the first time in 20 years, Australia had an inflation rate in line with world best practice,” Macfarlane said in his Boyer Lectures.

In the depths of the current crisis, with our trading partners and allies in recession, uncertainty is the norm.

We just don’t know what will happen to global supply chains and export markets.

“Structural change is a significant source of uncertainty,” Treasury said in its July forecasting exercise.

“The health and economic shock has changed many aspects of the way people live, including the way people work, shop and socialise, and it is unclear how large and persistent some of these changes will be”.

Recessions remake nations, destroying and creating at will, changing lives, industries and the social fabric.