Analysts query RBA’s rosy outlook and bank plans to extend Covid stimulus anyway

Economists question its rosy assessment of the economic outlook but the RBA plans to extend its cash injection until at least mid-February.

Economists have questioned the Reserve Bank’s rosy assessment of the economic outlook after it said it will push ahead with plans to start gradually turning off its massive stimulus program.

However, the central bank plans to extend the cash injection until at least mid-February due to a “temporary setback” from Covid lockdowns.

While the RBA’s decision to leave its cash rate and three-year bond rate targets at a record low of 10 basis points was widely expected, a majority of economists expected the central to push back a so-called tapering of its bond buying from $5bn to $4bn a week after slashing its economic forecasts in recent weeks.

Financial markets took the decision in their stride, as the commitment to extend the bond-buying program will have a similar effect on its balance sheet as a deferral of tapering, particularly since most assumed that the RBA had planned to taper its bond buying again in November.

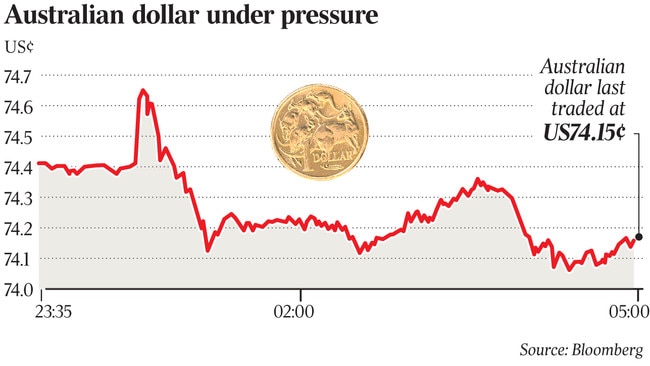

The 10-year bond yield closed flat at 1.26 per cent, the dollar hit a two-day low of US74.1c and the S&P/ASX 200 index recovered from an intraday fall.

But AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver said the RBA’s assessment was “very optimistic”.

“While we agree that the setback in the recovery will be temporary and see strong growth through next year, we thought that the hit flowing from the expansion of the lockdowns to Victoria and the ACT and the extension of the NSW lockdown since the last RBA meeting would constitute ‘the more significant setback for the economic recovery’ the RBA had signalled in its last minutes it would be prepared to act on,” Dr Oliver said.

“In the event the RBA clearly has a higher hurdle to change course on the taper, and has simply chosen to turn it into a longer, slower taper, at least for now.

“However, while the RBA has not provided updated growth forecasts it still looks very optimistic on the outlook for the economy into early next year.”

Dr Oliver expected the lockdowns since May to wipe $28bn off the economy and cause a 4 per cent contraction in the September quarter.

Combined with the likelihood of a high number of coronavirus cases persisting in the December quarter when vaccination targets are reached in late October/November, he saw a “more gradual reopening and more depressed confidence as we ‘learn to live with Covid’.

Growth this year is therefore likely to be around zero versus the RBA’s recent forecast of 4 per cent and, while strong growth next year of about 6.5 per cent is expected, due to pent-up demand and as confidence in vaccines keep hospitalisations and deaths manageable, he said the level of activity would be significantly lower in 2022 than the RBA had been assuming.

Full employment – which is expected to need the unemployment rate to fall to about 4 per cent – “has therefore likely been pushed out by around six to 12 months”.

Continuing the purchase of bonds at the rate of $5bn a week may not have resulted in a big boost to economic activity and the speed of the recovery next year. Moreover, the heavy lifting will need to come from fiscal policy.

But it could have helped by keeping longer bond yields and hence fixed mortgage rates lower and the value of the dollar lower than would otherwise have been the case, Dr Oliver said.

“Starting the taper three months or so ahead of the Fed also seems a bit risky given the weaker near-term outlook facing Australia in contrast to the US which is continuing to reopen,” he said.

ANZ’s head of Australian economics, David Plank, said the RBA’s decision to push out the review period for its bond buying to February rather than delay a taper this month in response to lockdowns was “confusing”.

“Presumably it is this medium-term outlook that explains why the RBA stuck with its July decision to taper bond purchases from September,” he said.

“But it is not entirely clear to us why the board felt the level of uncertainty was insufficient to delay tapering but sufficient to push out the review. The message is somewhat confusing.”

Still, he noted that the impact was largely the same in a practical sense, as the RBA would end up buying more bonds than it previously planned to, albeit at a slower rate.

“We think this is the appropriate decision given recent developments,” he added.

But Fidelity cross-asset investment specialist Anthony Doyle said the taper decision was a “step in the wrong direction” given surging Covid-19 cases in August that have put the two most economically significant states – accounting for 55 per cent of GDP – into extended lockdowns.

With unemployment likely to rise materially in the September quarter and wages rising by a tepid 1.7 per cent over the year to the end of June, more had to be done to drive the economy towards full employment in the short term, according to Mr Doyle.

A weaker currency and lower bond yields via an expansion of the QE program would have assisted in meeting the inflation and employment goals of monetary policy, and an increase in bond purchases – rather than a reduction – would have been a better idea.

While the RBA expects the economy to bounce back quickly once virus outbreaks are contained, it is unclear how much economic scarring has occurred due to the extended lockdowns that residents of both states are experiencing.

“It does appear that the RBA board has been too cautious in its approach to supporting the economy, as evidenced by its own forecasts of below-target inflation and weak wage growth in 2022,” Mr Doyle said.