When Crown started its full operation in 1997 it recognised the vital importance of casino governance and that recognition continued for many years.

But over time the Crown board attracted people who had wonderful achievements in the non-casino world - particularly media - and the importance of this core skills base was gradually relegated.

As we have seen in both the Sydney and Melbourne Crown inquiries, the result was catastrophic. The company has been blocked from Sydney and is in danger of losing its Melbourne operating licence.

Could other companies make the same mistake? In a changing world many enterprises are finding that their core business has changed and they need totally new skills. Many other companies could be caught with a similar core enterprise miscalculation which might endanger the business.

To fully understand what happened at Crown we have to go back to the start.

When Crown started its operation in 1997, casino governance was integral to its operation.

But as the years passed the Crown board attracted people who had wonderful achievements in the non-gaming world, particularly in media.

Indeed at times the Crown board would have been perfect to run a television station, newspaper or radio business.

Few of the success areas of the board members required governance as an integral part of the operation - in media the doctrine of freedom of the press requires totally different skills.

The successful Crown bid for the Melbourne casino was driven by Hudson Conway, led by the late Ron Walker, Lloyd Williams and Rod Carnegie.

Gaining the licence was a long, drawn-out process, with strong opposition to a casino. Very detailed operating requirements were put in place which enshrined in Crown that governance had to be a key core competence.

Lloyd Williams fell in love with the task of building a casino and entertainment complex that he regarded as perfect. Sections of the building were constructed and if Lloyd didn’t like them he pulled them down and did it differently.

The company should have raised extra capital to fund its ballooning cost. Instead it borrowed money and when that dried up Williams turned to his friend James Packer to buy out the business.

Crown became part of the Packer media business, although it was later separated.

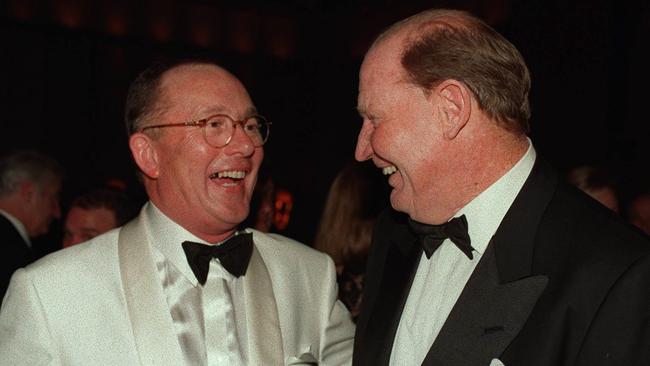

James Packer had a unique ability to attract talented people to the Crown board. I looked up the 2008 board where John Alexander was deputy executive chairman under James Packer as executive chairman. Alexander was former editor-in-chief and publisher a The Sydney Morning Herald, and editor-in-chief of The Australian Financial Review.

Others on the board and their skills base included Chris Anderson (CEO of Optus and John Fairfax), Chris Corrigan (Patrick Corporation), Rowena Danziger (headmistress at Ascham School in Sydney from 1973 to 2003), Geoff Dixon (Qantas), Ashok Jacob (Pratt Group),

Michael Johnston (Ernst and Young), David Lowy (Westfield) and Richard Turner (Ernst and Young).

Ten years later, in 2018, John Alexander, Geoff Dixon and Michael Johnston were still there but a new crop of directors had arrived, including high-profile directors such as Helen Coonan, Andrew Demetriou and Harold Mitchell.

Looking back, James Packer was clearly brilliant in selecting directors with proven talent records in non-casino businesses.

But many of the directors had come because they knew, or had a friendship with, James Packer.

The first sign of danger came when Packer himself suffered illness and became less involved in the business. In some ways Crown was a listed family business and any family business where the main entrepreneur is struggling health wise faces a danger.

There is normally an event that gives the board a chance to perhaps take early drastic action.

In hindsight it happened at Crown in 2017 with the arrest of key people in China. It was a warning that something was seriously wrong on the governance front.

But hindsight judgments are easy. The longstanding CEO stepped down but the company needed to go much further and it should not have stretched into a Sydney application.

That was a clear sign that it had not recognised the seriousness of the Melbourne governance problem.

But, of course, Sydney was the James Packer dream. He did not realise that the base operation in Melbourne had lost one of its essential skill bases and therefore was not only unsuited to go to Sydney but needed severe remedial work.

More Coverage

The casino business is unique. Governance is very important in every enterprise but in a casino it goes much further--- it is an integral part of the operation and one of the core operating skills required.