‘We were about to stop the trains’: How Trump’s tariff blitz is hitting business at home

The CEO of US aluminium giant Alcoa is at the very front lines of a global trade war. Bill Oplinger has offered a revealing insight on navigating the new world.

Bill Oplinger has spent more time in Washington in the past 100 days than any time of his life

There’s good reason for this. The Alcoa chief executive is at the very front line of Donald Trump’s trade war, and when 25 per cent tariffs were slapped on aluminium imports into the US in March, that affected him in a big way.

Alcoa and Oplinger might be based in Pittsburgh, overlooking the Allegheny River, but the aluminium major is globalisation in action.

Oplinger operates smelters and mines on nearly every continent, including the Portland smelter in western Victoria and another smelter in energy-starved Spain. Alcoa also operates three smelters in electricity-rich Canada, producing millions of tonnes of aluminium used in cars, planes, packaging or construction.

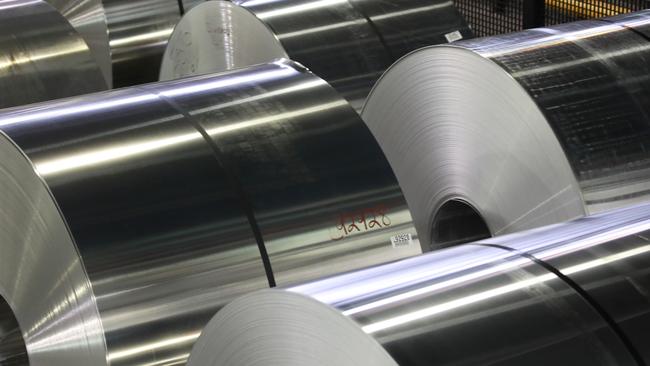

Think of Alcoa as a big, finely-tuned logistical machine constantly shipping bauxite or alumina (the key ingredient in aluminium) to its own smelters or other customers across borders, including the US and throughout Asia. Tariffs are a big spanner in the works.

“The US market is tremendously short aluminium,” Oplinger says during a wide-ranging talk at The Melbourne Mining Club.

There are only four small aluminium smelters left in the US – Alcoa owns two. There simply isn’t the capacity in the US market to produce all the aluminium that is needed. Indeed, the entire market is short 4.2 million metric tonnes of aluminium a year. The Trump tariffs are putting a 25 per cent hike on all the metal that comes in.

The net effect is $US100m off Alcoa’s bottom line. But there’s more than that.

Oplinger brings in metal from Canada, where his massive smelters run around the clock, powered by low-cost, clean hydro-electricity. This is the clincher. Every job in Canada involved in aluminium supports around 13 jobs in the US, Oplinger says.

The comments by Oplinger in Melbourne gave a close insight into how US businesses – big and small – are attempting to navigate Donald Trump’s brutal tariff regime.

Companies across the S&P 500 from tech to manufacturing and in Alcoa’s case, heavy industry, are grappling with extreme changes to tariffs often in real time and the prospect of pushing the US into a recession. CEOs at Oplinger’s level also risk becoming political targets if they speak out too forcefully, so for many it’s a cautious act of advocating or not engaging at all.

Oplinger says he will continue to push for free trade on behalf of Alcoa.

“We understand completely if certain governments, for strategic reasons, feel that they have to put tariffs in place, we understand that. We’ve worked with the administrations over 135 years. We’ll work with them again, but we clearly prefer free and fair trade.”

Trump’s ambition of bringing manufacturing back to the US with the tariffs might be an ideal, but the numbers simply don’t stack up.

Manufacturing capacity

To build refining capacity to bridge the shortfall will take years and cost $US35bn from a standing start. There’s only two big western players with the capacity: Alcoa and Rio Tinto. Then there’s the energy, with tens of gigawatts of additional demands. A hyper-scaled data centre has nothing on the amount of power that just one aluminium smelter consumes.

Then there are the ingredients.

“The value chain of aluminium starts with bauxite. There’s no more bauxite left in the United States – that was all mined out before World War Two,” he says.

Oplinger says Donald Trump’s motive is fair: “We absolutely support having a competitive, strong manufacturing environment in the US.”

However, the best way to do this “is to make sure that metal comes from Canada”.

It’s early days, but so far he hasn’t seen a drop-off in demand for Alcoa’s products, although US prices are starting to rise. But the bigger second-order impact is around the uncertainty it’s creating – particularly as tariffs and reciprocal tariffs are moving around so dramatically. A round of country by country negotiations during the 90-day pause is likely to lead to further uncertainty.

In mid-March when the President declared a 25 per cent tariff would be placed on steel and aluminium, Oplinger was hosting an event at Massena, New York where Alcoa operates one of the world’s oldest smelters. In the morning, Trump announced the 25 per cent tariff on all aluminium products would go into place from that evening. During the same day, Trump threatened the tariffs would escalate to 50 per cent.

“A 50 per cent tariff drastically changes trade flows into the United States,” the Alcoa boss says. “We were making decisions to stop shipping from Canada into the United States, and we were about an hour away to stop all rail cars from Canada into the United States.

“However, later in the day, at around four o’clock, it reverted to a 25 per cent tariff, which allowed us to continue to ship – even though that’s not optimal”.

WMC deal

On the sidelines of the lunch the long arc of corporate history was at play. Oplinger, who represents Alcoa’s new generation, for the first time met the former Western Mining boss Hugh Morgan.

“For me, it’s just a legendary name,” Oplinger says.

It was Morgan who really kicked off Alcoa’s multi-decade connection with Australia, including bringing in the US company as a partner and operator in the Portland aluminium smelter.

It was Morgan who spun out WMC’s interest in aluminium venture into the ASX-listed business Alumina, in doing so essentially inviting Alcoa to pay a premium to exert full control for what was essentially a holding company.

The bid never arrived. But Alumina outlasted the parent, as the demerger cleaned up WMC’s structure that drew out bids for the prized Olympic Dam copper mine. Xstrata had a shot, but it was BHP’s balance sheet heft that won the day.

Oplinger finally pulled the trigger on the $3.8bn Alumina buyout last year. It was the buyout that was 20 years in the making. Oplinger revealed on Thursday there had been as many as five attempts over the past two decades under various management teams where merger talks were held.

As always, it takes two to tango on deals like this.

Alcoa itself had split off its downstream engineering business Arconic in 2016. So the joint venture Alcoa operated with Alumina had moved from becoming a small part of the business to a much more meaningful operation.

From late 2023 the share prices had both moved in the direction of each other, including weakness in Alumina where it made financial sense to do a deal.

“There is tremendous industrial logic for putting the two companies together. So at the end of 2023 there was really a window of opportunity to get the deal done,” he says.

The question of Portland’s longer future comes up every five or so years, although this was recently put to bed with Portland now operating under long-term power contracts until 2035. Oplinger acknowledges Portland has its challenges, even though the plant is among the biggest in Alcoa’s 12-strong refining portfolio.

It’s a long way from the two major markets in Europe and North America for a start, and a long way from power generators.

Over time, Portland’s viability comes down to low-cost energy sources, Oplinger says. On the current technology, renewables won’t get it there alone. That means having a robust domestic gas policy that will allow Portland to be competitive among the world operators.

“I’m always hopeful, Oplinger says. “I always want to keep our plants operating. There’s a lot of time for things to change”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout