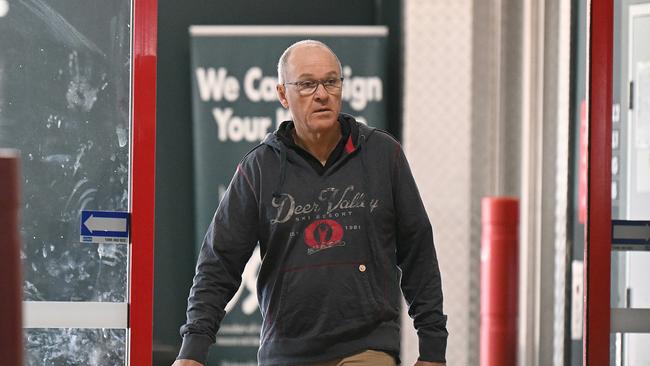

PwC boss Tom Seymour and others quit board amid imminent tax scandal

The personal investments of PwC bosses are in the spotlight, as former CEO is revealed as one of two execs to quit a controversial education provider before tax blow up.

Former PwC chief executive Tom Seymour and a senior colleague quit their roles with a controversial education provider they had invested in, as the consulting firm’s tax scandal was blowing up.

Mr Seymour and PwC tax expert Kai Zhang were long-time directors of the Hong Kong-based Top Education, where eight PwC executives or their family members invested personal wealth when PwC took a separate, 15 per cent stake in the enterprise.

The personal investments, which have attracted a backlash among some PwC partners who have raised concerns of potential conflicts of interest, are noted in a Top Education document filed in Hong Kong.

The timing of the resignations from the board is seen internally as potentially critical, taking effect on November 18 last year, just days before the scheduled annual general meeting in Sydney.

There were internal questions about the decision of the two and other senior PwC figures to invest their personal money several years ago in an area where the company had a direct investment.

The Top Education resignations came within weeks of the company having to deal publicly with the fallout over disgraced tax partner Peter Collins.

Before Mr Collins left PwC, he told colleagues he was planning to travel to Europe for the Australian summer break.

Mr Collins, a global tax expert who worked from a hot desk while pulling in millions from the consulting giant, was revealed publicly in January to be part of a tax policy conflict-of-interest scandal that is threatening to destroy the organisation.

Colleagues said Mr Collins, who was well liked, was a victim of a corporate execution in a manner similar to an episode of pay-TV cowboy drama Yellowstone.

“They take people to the train station, they just shoot them and throw them off a cliff. Collins and others got taken away,’’ an insider said.

Before this was made public, Mr Seymour removed himself from the Top Education board, as did Mr Zhang, who was an alternate director to Mr Seymour.

The Weekend Australian asked PwC why the pair quit Top Education, whether they were told to quit by PwC, whether PwC was reviewing private investments in Top Education, and whether the investments were in line with global company practices. The company responded: “It’s not uncommon for professional services firms to take equity positions in other service organisations.

“However, we will continue to take the necessary steps to address our culture, governance and accountability to better meet the expectations of the community.

Top Education was the entity that was revealed nearly a decade ago to have provided $1600 to former Labor powerbroker and senator Sam Dastyari to help meet a travel expense, which helped trigger his demise.

Top Education acts as a private tertiary education provider in Sydney. The ABC has reported that PwC failed to declare its interest in Top Education while conducting a review into the national regulator of private colleges.

The Top Education investment by eight high-profile PwC staff or families – including the wife of former chief executive Luke Sayers – is expected to form part of the company’s review of the way PwC has functioned in the past decade. amid claims of a two-speed business where elite partners allegedly worked under different rules.

The Weekend Australian is not suggesting any wrongdoing by the senior PwC figures – past and present – but is merely reporting the internal debate occurring about the company’s setbacks.

Mr Sayers now runs his own consultancy firm, Sayers.

A spokesman for Mr Sayers said the businessman did not discuss his personal investments.

It is understood that there were processes in place to enable the hundreds of PwC partners to co-invest in some assets and that any investments needed to be formally approved.

The Weekend Australian has spoken to senior figures who are fighting to protect the reputations of thousands of staff caught up in the scandal, which started with the tax leak scandal, engineered by Mr Collins, and has led to the offloading of PwC’s government functions in Australia.

The firm’s new leadership has been made aware of a series of alleged wrongdoings over many years, which included salacious claims of inappropriate nondisclosure agreements to cover up problematic internal relationships.

None of the claims has been publicly ratified.

Incoming chief executive Kevin Burrowes – or the people around him – have been asked to consider whether past expenses claims by some partners can be justified.

One senior PwC source said there had been rumours of largesse in the organisation and basic conflicts of interest for years.

Other sources in the consulting sector say PwC has in recent years been very aggressive in pursuing profits that flow to partners, which has arguably influenced the culture at the firm.

Some partners at PwC in the government consulting sector also feel they have been “thrown under the bus” by the actions of non-consultant partners, and now face having to answer to new bosses at private equity firm Allegro.

The PwC scandal has rocked the Australian corporate community, with leaders of other businesses anxiously looking on.

At this week’s annual meeting of CSR shareholders the company’s auditor, Deloitte partner Joanne Gorton, was asked if she, or any members of her audit team, had worked for PwC in the past 10 years.

Ms Gorton said that while no other members of her team had worked at PwC, she had spent time there before joining Deloitte seven years ago.

Her LinkedIn profile reveals she spent 19 years at PwC, working her way up to partner before switching sides.

CSR chair John Gillam followed by saying of the tax-leak scandal: “It’s a very important issue. And obviously, like all of us in the Australian business community, we’re watching very closely what’s unfolding there.”

Top Education’s internal documents described the nature of the personal investments by the families of Mr Seymour, Mr Sayers and others when PwC invested in the company in 2016.

It is clear the investments were personal and made alongside the PwC investment.

“The third-round investors are partners of PwC Australia or their related trusts who made investments in our company as personal investments that are unconnected with and independent of PwC Australia and independent of PwC Australia and PwC Nominees,’’ the document reads.

Mr Zhang – then PwC’s China practice leader – said in 2016 in an official statement that Top Education was considered to be ‘’highly regarded in China’’.

“This investment in an alliance with Top Education positions us to capitalise on the rising demand from China for Australian tertiary and executive education services,’’ Mr Zhang said at the time.

He referred The Weekend Australian to PwC when approached for comment.

Mr Seymour said in 2016: ”Australia needs the services sector to step up and fill the gap left by the slowing demand for commodities. Education-related exports present one of the most promising areas for growth.’’

Mr Seymour quit PwC in May after being outed as one of dozens of partners who received emails about confidential information obtained by Mr Collins.

Mr Collins was asked 10 years ago to help frame laws to get large foreign companies to meet tax obligations in Australia.

The Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL) was meant to prevent big companies from shifting profits from Australia to other countries with lower tax rates.

Mr Collins signed a series of confidentiality agreements but he ignored the legal restrictions, according to the Tax Practitioners Board, which found that he shared that information within PwC.

This handed the company a financial advantage by being able to act early on the information. That internal information then enabled the company to prepare to act quickly on the reforms once they were announced by government.

A source familiar with internal discussions told The Weekend Australian that anger was being directed at a core group of senior PwC staff who had been motivated by making money and that too little attention allegedly was given to ethical considerations.

The source said it was only a 50 per cent chance that PwC could survive the controversy because of the reputational impact, which already was starting to show, with less interest from some previously strong clients.

While there had been a heavy focus on the scores of people who had allegedly received information on the Collins tax information, not all had been working on the matter or had an opportunity to exploit the information.