Pandemic challenge ‘like a far-fetched horror movie’

Gillian Franklin has run her Melbourne cosmetics business for two decades but has never seen anything like this.

Gillian Franklin has resolutely run her Heat Group cosmetics business in Melbourne for two decades through a breast cancer diagnosis, volatile business cycles, a sophisticated cyber attack, intense legal battles and a global financial crisis.

But nothing, she says, comes anywhere near the complex, multidimensional threat of the coronavirus.

“When I’ve confronted other challenges in my career, I was able to scope them out and find a solution,” Franklin tells The Weekend Australian.

“But COVID-19 is like some far-fetched horror movie; it’s quite surreal.

“We’ve had to recalibrate everything we do.”

While there are some broad similarities with the last recession in the early 1990s, the economy’s whiplash-inducing crash in the June quarter is in a category of its own.

Treasury’s economic and fiscal update last month said real GDP would fall by 3.75 per cent in the 2020 calendar year — the biggest contraction in activity since official records began.

Unemployment was forecast to peak at about 9.25 per cent in the December quarter.

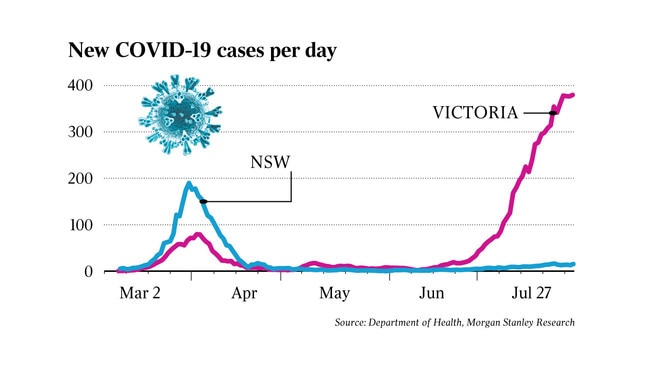

Some economists are convinced that any extension of Victoria’s second lockdown, scheduled to last six weeks this time instead of four weeks, could tip Australia into a third consecutive quarter of negative growth — a grim sequence not seen since the 1982 recession.

Heat, like its founder and chief executive, is battle-hardened and will survive.

Franklin recognised early that flexibility and adaptability in her staff and the company’s product range would be critical.

She pushed her low-cost, popular brands (MUD, Ulta3 and Essence) hard, knowing that many households would be short of cash in the inevitable recession, and in a record four months developed a sanitiser from the initial concept to stocking retail shelves across the country. COVID-19, however, is a constant, malign presence.

Victoria and NSW account for well over half of Heat sales, and the southern state currently has the lead role in Franklin’s supposedly far-fetched horror movie.

After two days of lower infections raised hopes that the COVID-19 curve was flattening, Victoria again plunged into despair on Thursday, reporting a spike in daily cases to a record 723.

Friday was little better, with a further 627 people infected.

With the state now in the second half of its lockdown, Daniel Andrews said there was no option but to prioritise public health.

“In my discussion with (Scott Morrison on Thursday night), there is a complete acknowledgment that there can be no economic recovery until we deal with this public health challenge,” the Premier said.

“It is incredibly difficult — in fact it’s almost impossible — for us to see businesses recover and survive, unless and until we get these numbers down.”

Memories of the 1990s recession have faded, including the evocative image of 250 trams parked in central Melbourne for 33 days from January 1, 1990.

The trams didn’t move because the Cain Labor government shut down the power grid in response to a strike over its plan to introduce scratch tickets — an initiative which would have resulted in 550 ticket conductors and the same number of train station staff losing their jobs.

In August 1990, Joan Kirner succeeded John Cain as premier but the political divisions only widened.

When opposition leader Alan Brown asked Kirner in parliament if she would finally confirm that the state was in a recession, the premier responded: “I sometimes wonder whether the opposition is actually an opposition, or the fifth column trying to undermine the Victorian economy.”

Company director Dianne Smith-Gander, who was chief of staff to then-Westpac chief executive Frank Conroy at the time, says there are parallels and differences between the two recessions.

On both occasions, employment growth and job protection have been seen as absolutely paramount.

“What’s different this time is the level of uncertainty and the inability to plan, so you’re at a certain point, you make your plan and all of a sudden you’re no longer there,” Smith-Gander says.

“I’m also getting an eerie sense of deja vu, because in the 1990s there was a blame game with people externalising their experiences and looking to scapegoat others.”

COVID-19, in contrast, was initially greeted by a robust community spirit, but this was now starting to fray.

“I see directors on-screen and they’d rather be poking their eyes out with a pencil, when initially we were all highly engaged and could see the upside, from bringing in experts remotely to spending less time on planes,” she says.

“It feels like the beginning of the last recession — people are missing that physical interaction; they have Zoom fatigue and they’re looking for someone to blame.”

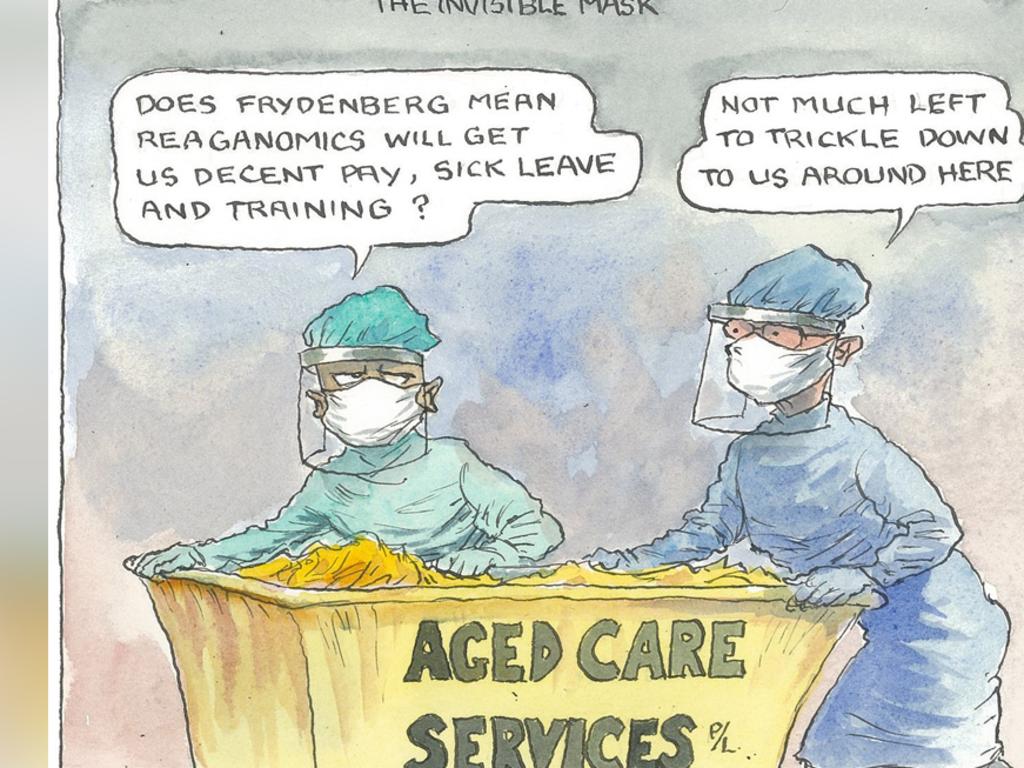

In a speech to the National Press Club a week ago, Josh Frydenberg validated the overwhelming impression that the snap recession brought about by COVID-19 was much sharper than its predecessors in the 1990s and 1980s. The falls in GDP and employment are about twice as big, and occurred over a matter of months, not years.

In those recessions, working-age men in the manufacturing and agricultural sectors bore the brunt of the downturn, whereas this time women have suffered higher job losses than men.

Younger people have also been badly affected, making up more than one-third of the jobs lost.

Youth unemployment has jumped to its highest rate in 20 years.

Don Russell, chairman of the nation’s biggest superannuation fund AustralianSuper and principal adviser to then-treasurer Paul Keating in the last recession, says the 1980s boom came to an abrupt end as interest rates were pushed to 16-17 per cent “almost in desperation”.

“There was a speculative fever which ran through to 1990,” Russell says.

“People felt that it was OK to have interest rates at 17 per cent if asset prices were increasing at 20 per cent.

“But almost overnight the place came to a grinding halt.”

Famously, it became Keating’s recession that “we had to have”, and in brutal economic terms it presented policymakers with an opportunity to rid the system of inflationary expectations and set it up for an extraordinary 29-year period of uninterrupted growth.

“This time (the recession) is much more deliberately engineered, and the risks get greater the longer that the period of disruption continues because you can develop scarring and build in dislocation that wasn’t there before,” Russell says.

“Companies can lose the capacity to do things, and some sectors like tourism and universities will have a lot of trouble recovering.

“So it’s different in that sense, even though in both cases the economy is recovering from a shock.”

The AustralianSuper chairman takes great heart from the collaborative response of the federation to the pandemic, highlighted by a sense of purpose in the national cabinet to fix problems instead of falling back on political point-scoring and ideology. By listening to expert advice, he says, Australia got close to elimination of the virus before things got out of hand in Victoria.

Until that point, the nation was able to achieve similar health outcomes to New Zealand while a large part of the economy continued to function.

John Edwards, a former Reserve Bank director and Keating’s economic adviser in the 1990s recession, echoes the main frustration of many with the pandemic.

It’s a shapeless, relatively unknown force with the ability to reinvent itself and again wreak havoc, just when you thought you had it beaten.

In the 1990s, though, policymakers at least knew what they were dealing with.

“High interest rates had brought the economy to a halt but there were also structural improvements working their way through the system,” Edwards says.

“It was a challenge but all the pieces of the jigsaw were there and you knew the dimensions of the problem.

“This time there’s a big unknown — the whole thing could become unstuck because of an inability to control the spread of the virus.”

These are precisely the issues that Franklin is dealing with at Heat.

Last month, for example, one of the company’s major retailers, Woolworths, closed its distribution centre in the inner Melbourne suburb of West Footscray after a worker tested positive to COVID-19. Heat couldn’t ship any product to the facility.

Other customers have banned face-to-face meetings with sales representatives, and airfreight and shipping from offshore takes longer, with the cost of airfreight trebling.

Franklin says staff are anxious, and everyone’s nervous about their jobs and health. “The only thing that’s certain is uncertainty, and it’s hard to write a business plan around that,” she says.

Fundamentally, though, the Heat founder is an optimist, much like Smith-Gander.

Even so, Smith-Gander believes that the challenges of COVID-19 are much bigger than we first thought. “We had this celebratory moment where we thought we’d nailed it but we celebrated too early,” she says.

“What we’ve learnt is that we need to respond to a COVID-19 future and not think we can go back to the past.

“As soon as we understand that, we’ll be better off.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout