Pacific Island nations using their moral authority to hold rich nations to account

Climate change is front and centre in the Pacific where Australia is pursuing green diplomacy as it tries to counter the influence of China.

There were slow claps and awkward smiles when Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese finally arrived for the traditional “family photo” at this year’s Pacific Island Forum in Tonga.

For island leaders, waiting in the hot sun, it was nothing new; Australia has always been an outlier in the regional bloc that’s united by the fear of rising seas. Albanese’s late arrival was far from the worst insult Pacific leaders have endured from an Australian prime minister, and they let it slide with good humour.

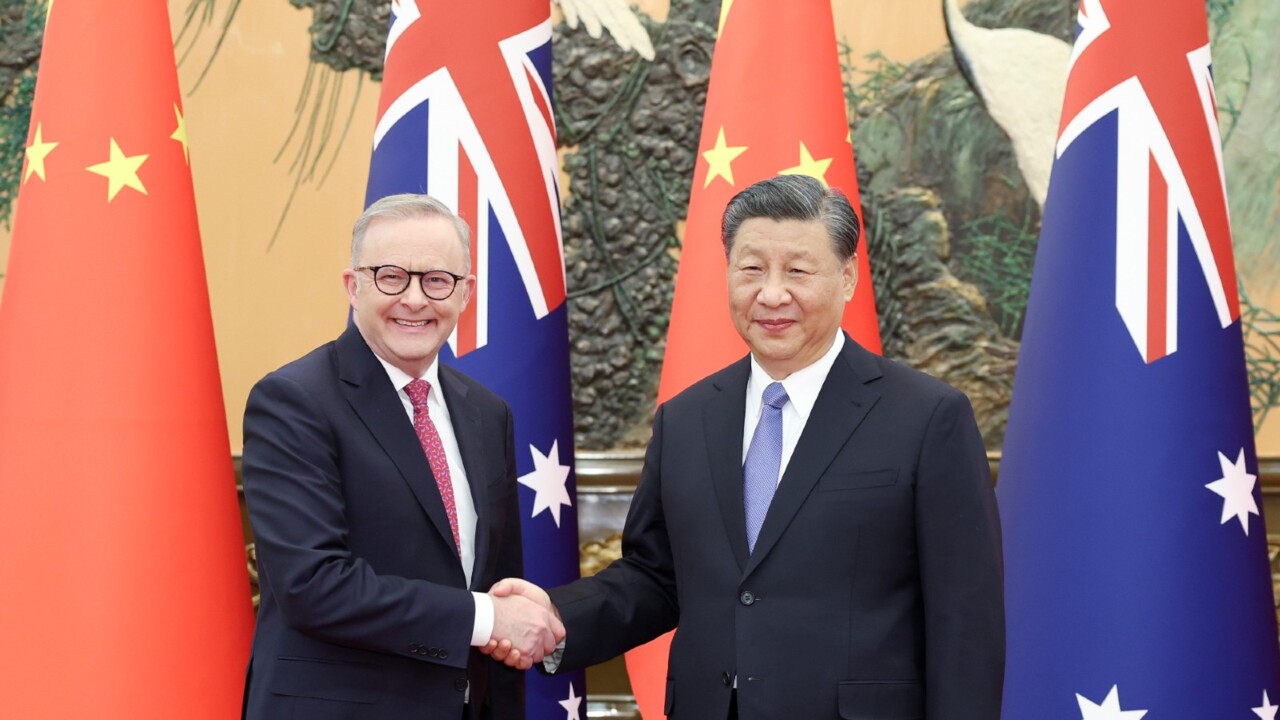

After all, Australia is once again taking their concerns seriously, pursuing green diplomacy as it tries to counter the influence of China in the region.

This is an article from The List: 100 Top Energy Players 2024, which is announced in full on November 22.

For their part, Pacific Island nations are also leveraging green challenges, using their moral authority to hold rich nations to account for the climate crisis – and to seek financial compensation.

In low-lying states across the region, the effects of climate change are already being felt in the form of more intense cyclones and droughts, king tides that threaten food and water supplies, and the failure of subsistence crops and fisheries.

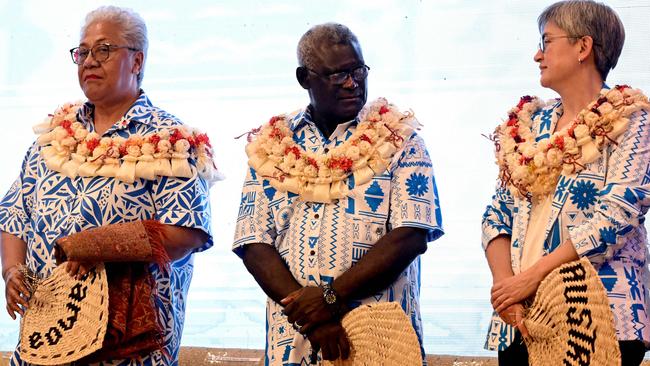

The region made clear its priorities in a landmark 2018 statement declaring climate change was the region’s most pressing security threat, beyond even the prospect of a military conflict between the US and China. “Climate change is the number-one priority in the Pacific, and they’ve made that clear themselves,” Foreign Minister Penny Wong tells The Australian. “It has never been the sort of political football that it has been in Australia. So we understood, when we came to government, that if we were going to retrieve Australia’s position… that climate had to be central to that.”

A world-first agreement on climate refugees has been among the most far-reaching outcomes of Australia’s renewed regional diplomacy. The Falepili Union with the tiny atoll nation of Tuvalu could become a template for how the world deals with people pushed out of their lands through climate change.

Named for the Tuvaluan word for being a good neighbour, the agreement provides 280 visas a year for Tuvalu’s people to settle in Australia and includes a guaranteed migration pathway for its entire population if its islands go underwater. It also acknowledges Tuvalu’s sovereignty over its fisheries and other maritime resources should its islands disappear, setting an important new standard as sea levels rise.

Albanese hailed the agreement as an offer of “mobility with dignity”. But it came with strings attached, giving Australia a veto over Tuvalu’s future security partnerships. Countering China underpins Australia’s diplomatic calculations, while opening opportunities for the Pacific.

The Falepili agreement is an “amazing deal” for Tuvalu, according to Professor Stephen Howes, from the Australian National University’s Development Policy Centre, who says the strategic interests at play helped greatly.

“China has changed everything, enabling Tuvalu to transform its migration relationship with Australia in return for the security concessions Australia obtained,” he says. “The Falepili treaty will be of enormous benefit to Tuvaluans, and, for Australia, has set a new and welcome benchmark for its deep, bilateral integration with the Pacific.”

Howard Bamsey, a former climate envoy and a long time COP summit negotiator, says Pacific Island leaders understand climate change in a way that few Australians do. “When ministers and heads of government wake up in the morning, they think about climate change because for them it’s existential,” he says.

Bamsey predicts future climate diplomacy will fuse environmental impacts even more tightly with security. “It’s really clear that for Australia’s regional security, helping countries to deal with climate change is essential,” he says. “But I think as the full implications of climate change become clearer … integrating the climate dimension of national security will be understood as really essential to the whole picture in a way that probably it isn’t yet.”

Regional security was top of mind for former prime minister Scott Morrison, who used his “Pacific step-up” to forge good relationships with key regional leaders in an effort to marginalise China. But his government was on the nose with the region more broadly, thanks to its climate policies, with the tensions coming to a head at the 2019 Pacific Island Forum in Tuvalu.

Morrison infuriated regional counterparts by defending Australia’s “red lines” – there must be no mention of coal in the summit’s final communique, no commitment to zero emissions, and no reference to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Fiji’s then-prime minister Frank Bainimarama said it was one of the most frustrating experiences of his life, describing Morrison’s conduct as “insulting and condescending”.

Wong capitalised on the ill-feeling, flying to Fiji just days after Labor’s 2022 election win to throw Morrison under a bus. “I understand that, under past governments, Australia has neglected its responsibility to act on climate change; ignoring the calls of our Pacific family to act; disrespecting Pacific nations in their struggle to adapt to what is an existential threat,” she told the Pacific Island Forum secretariat in Suva. “I want to assure you that we have heard you.” Wong has made at least 25 trips to Pacific Island countries since then, spruiking Labor’s net-zero by 2050 pledge, its interim 43 per cent target, and plans for a rapid shift to renewable energy.

Wong says the government is committed to taking climate action “because it matters, it’s important, and it’s real”. But she is open about the leverage it offers Australia as it tries to stay one step ahead of China as the Pacific’s preferred security partner.

“I’ve described us as being in a permanent contest [with China] in the Pacific,” Wong says. “It’s not where we were 10 years ago, or even five years ago, when that opportunity to be the only partner of choice was lost by those who were in these jobs previously.”

Australia hopes its plan to host the COP31 climate summit in 2026 in cooperation with Pacific Island nations could be another climate-diplomacy coup. The conference will be high-risk, throwing a spotlight on the nation’s status as one of the world’s biggest coal and gas producers. The Lowy Institute’s climate research fellow, Dr Melanie Pill, says there are serious concerns over Australia’s economic reliance on fossil fuels, “and it could reflect quite badly on Australia if these concerns are not listened to and actioned on”.

“To succeed, Australia will have to demonstrate diplomatic leadership skills similar to those France was applauded for when the world negotiated the Paris Agreement in 2015 – a truly historic outcome,” Pill says.

If Labor loses the federal election and Peter Dutton hosts the conference, it would be a jarring outcome for the Pacific; the Opposition Leader says he will dump Labor’s 43 per cent emissions cut by 2030, but remains committed to achieving net-zero by 2050 – potentially with the help of nuclear power.

His foreign affairs spokesman Simon Birmingham accuses Labor of “playing politics” with climate change in the region, saying Australia owes the Pacific “our honesty as well as our ambition”.

“Making promises Australia can’t or won’t meet is even worse than making inadequate commitments,” Birmingham says. “If we are upfront and honest with the Pacific, it needs to be not only about climate ambition but about how we get there.”

But despite serious questions over the cost and trajectory of Labor’s emissions cuts, Pill warns the Pacific won’t stand for any backsliding by Australia. “With every 0.1 of a degree Celsius temperature rise, the discussions intensify and the stakes are higher,” she says. “Every decimal point makes a huge difference in the Pacific, as miniscule as it sounds. For many Pacific Island countries, their sovereignty and territory is on the line.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout