James Dyson a whirlwind of ideas on Covid, WFH and Brexit

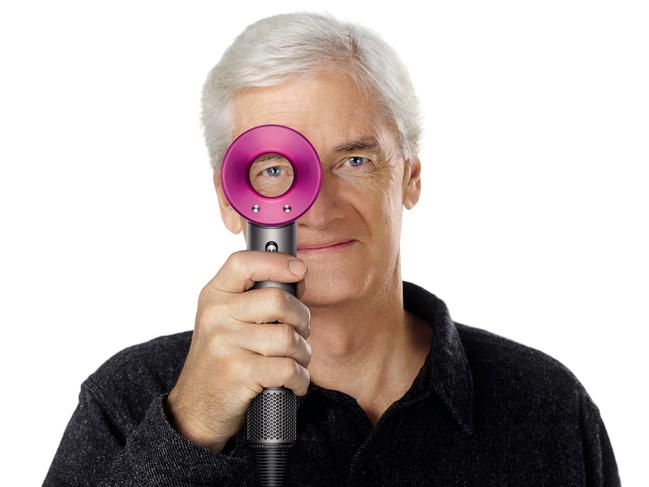

He spoke exclusively to The Australian from Dyson’s offices in Singapore in the week he launched a raft of innovations that take his famous vacuums to a new level of handy intelligence for the home.

The British billionaire — who topped the Sunday Times Rich List for the first time last year, worth £16.2bn — is using the COVID-19 crisis to disrupt his own business from within. And he warns about the perils of working from home and loading up the next generation with debt from education.

For consumers, the new V15 Detect Dyson vacuum is pitched as a game changer for hard floors: a built-in green laser set just above the ground is designed to spotlight the finest of dust. Sir James talked with gusto.

“At the moment when you vacuum, you can see thanks to our clear bit (another of our inventions) what you picked up, but you don’t know what you left behind because you can’t see the very fine dusts on the floor,” he said. “Our laser picks all that up, wrapping around each of the tiny dust particles. You can really see them in three dimensions.

“And even better than that, as it goes up, the machine counts and sizes those dust particles. So you know how many millions you picked up at each of the various sizes.”

The Dyson bagless vacuum was born of frustration in the late 1970s: vacuum bags routinely clogged up with dirt and lost suction power. Inspired by an industrial cyclone in a saw mill that used centrifugal force to separate dust, Sir James designed and built 5126 prototypes that used cyclonic action to suck up dust without a bag. Number 5127 was a winner.

He then took on an entrenched industry of bag producers, eventually starting his own business in order to sell his invention.

Today Dyson, a household name in Australia, operates in 80 countries and employs more than 16,000 people.

Cyclone technology is still the core of the latest product, separating and analysing particles from tiny pollen spores, to skin flakes and coffee granules, all displayed on an LCD screen as you vacuum. The screen also deals with run time anxiety — showing how much battery power remains.

Sir James “cut the cord”, as he puts it, when he invented the Dyson. There is an in-built comb to stop hair strangling the roller. And if there is a problem, up pops a pair of Sir James’s black rimmed glasses on the LCD pointing to the affected part.

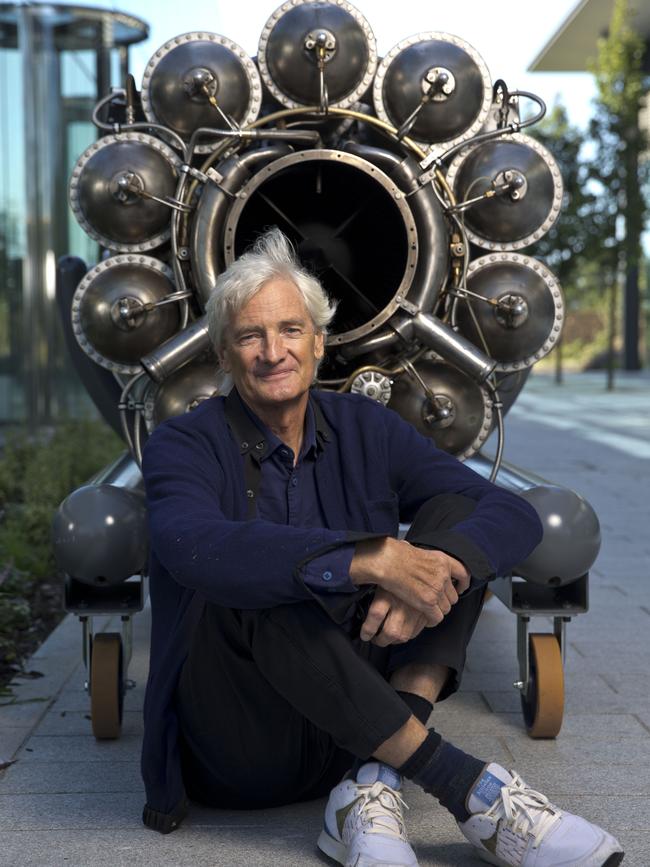

At 73, Sir James is both the face of the business and the hands-on manager. After 12 months of pandemic, he is now disrupting his own business model and working to cut out many of the retailers that sit between Dyson and its customers.

Dyson was one of the earliest manufacturers to feel the impact of COVID-19. “We are very strong in China and Asia, and we saw in January 2020 what was happening: January and February, factories were shutting down, supplies were being cut off, shops were being shut, people stopped buying and retailers were not ordering for stock,” Sir James said.

“So we had a crisis meeting in Paris and completely changed how we were going to do things. The world had been going direct anyway, buying online. And we knew that this would just accelerate that.”

Unlike other British manufacturers, Dyson did not use the government’s furloughing support program, but it did cut 900 jobs, 600 of which were in the UK.

“It was quite obvious during COVID-19 that retailers are going to be shut,” Sir James said. “We had a lot of staff directed towards supplying retailers and it is those staff that have largely gone, because we do things differently now, we’re selling direct. Companies are very different companies as a result of COVID-19.”

Dyson is creating new roles to speak directly to customers.

“We are asking people to buy direct from the maker, because why would you buy from an e-tailer, an Amazon, when you can buy direct from the manufacturer and have a direct relationship with the manufacturer?” Sir James said.

“It’s much better to know who you sell to and build a direct relationship, particularly as we go more and more connected, when our products become connected.”

Sir James’s future home is all about connecting. “Things will anticipate, rather than you having to react to situations — whether it’s a pollution incident, poor air quality, dust in your home. Our robots will go around and tell you all sorts of things that you don’t know at the moment and warn you in advance. Appliances will tell you before they go wrong.”

For now, Dyson is riding the latest obsession with the home: working from it and re-nesting it, all of which creates a lot of dust and increasing levels of toxins. After the 2019 fires in the east, Australian awareness of dust peaked, but Dyson is also targeting chemicals such as formaldehyde in furnishings and floor resins. A new era purifier, launched this week, takes in and destroys formaldehyde. A new stick cleaner, the Omni-glide, moves in all directions and under beds and cupboards.

For all the new business, however, Sir James is anti-home when it comes to work. “The really, really unfortunate thing, apart from the deaths and illness, has been that people have been working from home,” he said. “That is not a good thing, particularly in a creative business. But it is not a good thing anyway. I’m violently against it.”

The Dyson philosophy is a mix of good, old-fashioned values and an efficiency imperative that drives innovation. Not everything achieves commercial success: take the work in electric vehicles, or in new ventilators, which in the end was not required by the UK government. But R&D at Dyson is a constant.

A highly influential private operator, Sir James has a passion for education, farming and free traders. In June this year, the first students graduate from a four-year course at the Dyson Institute of Technology and Engineering at Malmesbury in Wiltshire.

“I’d never thought I’d have a university. It was suggested to me by Boris Johnson’s brother when he was the secretary of state for education,” Sir James said.

The institute offers skills in robotics to software, electronics, fluid dynamics and electric motors, and the institute is developing advanced battery technology.

“Anyone studying engineering at Dyson would have a wide range of disciplines to see in practice and to join in and develop and invent technology with the best scientists and engineers in the world,” Sir James said.

The chief innovator is horrified by the debts today’s students are taking on for living expenses and particularly tuition fees. “We actually pay our students,” Sir James said. “Some of them have cars, they’re quite well off. At the end of their course they have a job with us and I’m happy to say the first cohort, all of them, are staying with us. They have no debt, and they have been inspired to learn more academically because they are carrying out their engineering and practice.”

Where the serial entrepreneur is investing heavily is sustainable farming. Sir James grew up working on farms and has used his wealth to buy up major landholdings in Britain in a belief that self-sufficiency is the key to reducing the carbon footprint from freight.

“I’m a manufacturer and farming is about manufacturing food,” Sir James said. “I think we are the first carbon-neutral farm in Britain. We grow maize and make electricity to supply 10,000 homes. We are growing strawberries under glass during the British winter, so we don’t have to import strawberries, using the waste heat from our anaerobic digesters.”

Sir James has been most politically vocal on Brexit. After a multi-year battle with Europe over testing standards of products, Dyson has had a victory in the appeal court and is awaiting a judgment on damages, which have been put at £200m ($360m).

“The history of our legal case with the European Court of Justice is a salutary one. And of course it’s one of the reasons why I’m so vocally against being part of Europe,” Sir James said.

“To break free of this closed protectionist body and become a free trade nation, able to do deals with all over the world and in particular with the Commonwealth — I’m delighted. I don’t see why there should be any trade barriers at all. People in Britain should be able to enjoy Australian wine and Australian meat in the same way we can enjoy European wine or even our own wine. Why not?”

Sir James Dyson, inventor, designer, manufacturer, educator, Brexiteer and now Britain’s richest man, is showing no signs of slowing down.