Black Monday: ‘The music suddenly stopped, party was over’

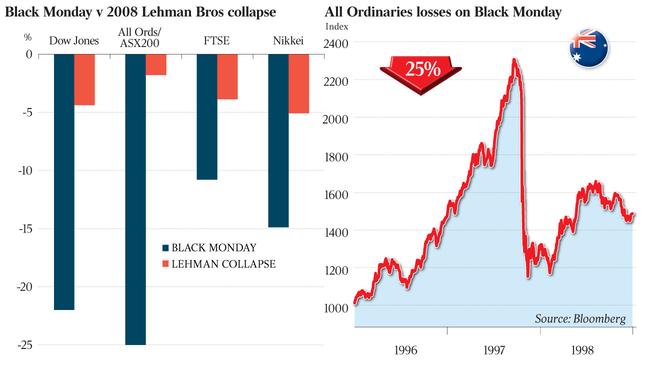

For many the 1987 crash, the biggest ever one-day fall in the Australian sharemarket, was the beginning of the end.

For many the 1987 crash, the biggest ever one-day fall in the Australian sharemarket, was the beginning of the end. Thirty years ago, a lethal combination of high interest rates and excessive leverage used to buy overvalued stocks wiped out speculators when the Australian market fell 24.9 per cent on Black Tuesday, October 20, 1987.

It also set the ball rolling against a generation of corporate raiders such as John Elliott, Alan Bond, John Spalvins and Robert Holmes a Court, who rode to fame and fortune on the back of sweeping economic reform, technological advances and easy money fuelled by the floating of the dollar and the opening of the banking market to foreign competition.

While they survived the initial shock of the crash, it exposed the flaws in the corporate structures that, along with rising interest rates, would eventually unravel their empires.

But the way Elliott, the chief executive and driving force behind Elders IXL, saw it at the time, the panic selling on Black Tuesday, October 20, was an opportunity. It knocked out a crucial impediment on his path to “Fosterising” the world and provided a buying opportunity.

Returning from his overseas honeymoon as the market was about to go into meltdown, the then president of VFL Australian football premiers Carlton ordered the Elders IXL super fund to pick up some stocks at knockdown prices.

“I thought it was a gross over-reaction. We actually made some good money in the months after that,” Elliot tells The Weekend Australian, as the 30th anniversary of the crash approaches.

More significantly, it ended an audacious bid for BHP by West Australian raider Holmes a Court.

Elders IXL was then the second-biggest company in the land, with interests across brewing, agriculture, mining and food processing, and it had risen to BHP’s rescue by taking a 19 per cent stake as part of a cross-shareholding deal that stalled the Holmes a Court bid.

But when prices crashed, Holmes a Court’s funding evaporated and he switched from aggressor to vendor, selling a swag of assets to keep the empire afloat.

“The crash took Holmes a Court out of the game and that allowed us to work out how to unwind things with BHP,’’ Elliott, then the chief executive and chairman of Elders, says. “And we got the money we needed to expand our brewing business.”

It was the later unwinding of the cross-shareholding that brought Elliott undone. When Elliott and a group of Elders executives used Harlin Holdings to buy the shares held by BHP, National Companies and Securities Commission chairman Henry Bosch ordered them to make a full bid. They ended up with 55 per cent of Elders, but the debt taken on to fund the bid sunk Harlin as interest rates rose to 18 per cent. Elliott resigned in 1990.

Some, like fund manager Geoff Wilson — who was broking Australian stocks in New York on Black Monday, as it was in the US — see some parallels with conditions then and now.

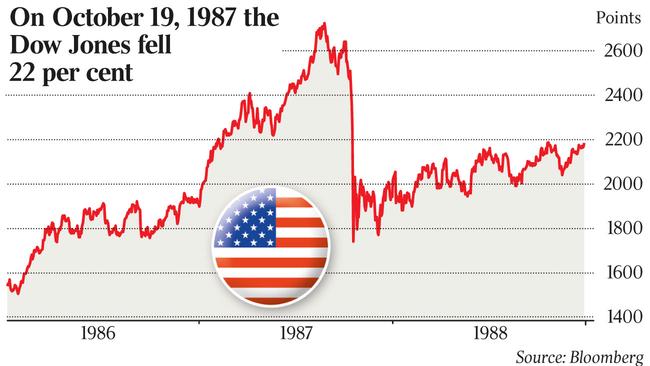

“I went out for a drink on Friday night to celebrate because I thought I was seeing history being made,” Wilson says of the 108-point fall in the Dow — then the biggest one-day points fall since 1929 — on the trading day before Black Monday in the US. “Little did we know what was coming.”

The US market had already fallen 9.5 per cent in the week before and Wilson says there seemed to have been a collective rethink over the weekend about the long bull market run, such that by Black Monday everyone wanted out.

“That triggered a 508-point, or 22.6 per cent, fall in the market, wiping out $US500bn of value, and triggering market plunges around the world, including Australia, the following day,” Wilson says.

“Very suddenly the music stopped. To me it looked like the financial system was disintegrating before our eyes.”

But if any lessons were learnt from the crash, they have not eliminated the risks that it could happen again.

Wilson reckons the excess liquidity driven by central bank responses to the global financial crisis leaves markets vulnerable to rising rates. Sharemarkets are trading on valuation multiples above their historic averages and exchange-traded funds could prove to be the modern equivalent of the portfolio insurance that exacerbated falls in the market in 1987.

“The market had been incredibly strong and in early 1987 everyone was saying the market was expensive, but it kept going up,” Wilson says.

“It is sort of like now — everyone thinks the market is a little bit expensive — but back then it goes up another 45 per cent (before the crash).”

Spalvins, who as early as late 1986 had called the market expensive and predicted a crash, doesn’t see any parallels in today’s market. “My argument — 87 versus 17 — is that the conditions are entirely different,” Spalvins says.

“Interest rates are different for housing,’’ he says, noting that mortgage rates were already at 14 per cent when the market crashed, and kept rising through 1989.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, both Elliott and Spalvins urge caution. “Can you imagine what would happen to housing, which is already expensive, if rates went from 5 per cent to 7 per cent?” Spalvins says.

Elliott says it is the property market that’s “a bit overdone”.

“I think right now I wouldn’t be in too much debt,” he says.

“You could get into trouble. When the economy picks up, and if inflation picks up with it, interest rates will have to rise.”

As for shares, Spalvins says conditions are nowhere near as ripe for a fall: “The market is in fact 20 per cent below where it was 10 years ago, whereas in 87 the market had doubled and trebled in five years.”

In 1986, Spalvins backed his view that the market was expensive by taking out a short position. But the market kept rising strongly through 1987 and, under pressure from his board, he closed it out.

His conglomerate Adelaide Steamship survived and went on to take over Ron Brierley’s Industrial Equity, winning ownership of Woolworths, and became the biggest private sector employer with it. But high rates and devastating reports by Barings analyst Viktor Shvets and Brierley himself exposed the high debt levels across the group and triggered its collapse into bankruptcy in March 1991.