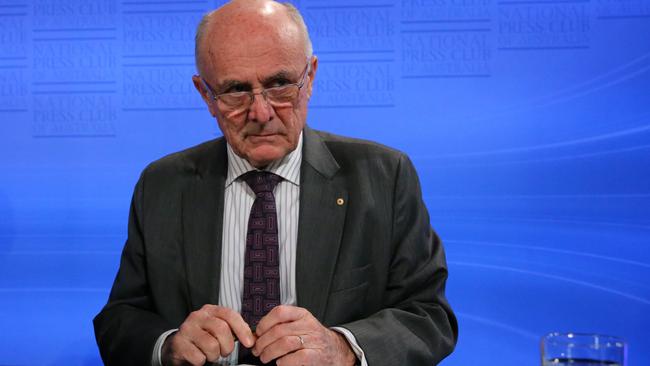

First competition regulator chief backs Green bid to break banks

Allan Fels has backed the Greens’ push to break up the major banks and AMP to curb gouging of customers.

The inaugural head of the competition regulator, Allan Fels, has called for a radical overhaul of bank regulation and structure, backing the Greens’ push to break up the major banks and AMP to curb gouging of customers and hidden subsidies to investment banks.

Revealing his “astonishment” at the revelations at the royal commission, Professor Fels, who chaired the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission from its inception in 1995 to 2003, said “deep structural conflicts of interest” would overwhelm piecemeal efforts to curb unethical behaviour. “There are inherent conflicts and it should be obvious they won’t be resolved by better behaviour by banks or better management by regulators,” he said. “I’ve been surprised, astonished, at the extent of unethical behaviour and it indicates to me banks can’t be trusted to deal with these situations fully.”

The Australian Securities & Investments Commission and the government are scrambling to toughen, and boost funding for, regulation following a damning final report into competition in the sector by the Productivity Commission.

Professor Fels, a distinguished economist, also slammed an increasingly embattled ASIC, which has reportedly hired external “spinners” to defend its reputation against charges of insufficient vigilance. “There’s no question the ACCC has been the far more serious enforcer for many years. It goes to court more often. It’s a better litigator. It has a culture of serious law enforcement. ASIC has not had such a culture,” he said.

The ACCC sent shockwaves through banking circles in June, issuing criminal cartel charges against ANZ, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank for what many bankers thought were routine business practices.

In a new policy announcement this week, Greens leader Richard Di Natale advocated a shift of responsibility for consumer protection and competition in financial services from ASIC to the ACCC. “ASIC has prosecuted only one financial services licence holder in the last decade,” he said in a statement.

The Greens policy would also compel financial institutions to operate in one of four markets — basic banking, wealth management, investment banking or insurance — a market structure that broadly existed in most countries until the 1990s.

Professor Fels said the Greens policy, “both the part about structural separation and changing regulation, needed serious consideration”. The Howard government rejected a similar proposal to give more powers to the ACCC in the late 1990s following the Wallis Inquiry, “under intense lobbying from the financial services sector”, Professor Fels said. “The key reason was ASIC was seen as ineffective then, and what we have is the same issue today.”

The royal commission turned its attention to superannuation this week, revealing further ‘‘fees for no service’’ scandals at National Australia Bank’s wealth management arm. The government also announced an extra $70m in funding for ASIC, in part to pay for regulatory staff to operate within major banks and AMP.

“There are a number of serious structural issues that need to be considered, the first and most obvious is the separation of the activity of creating financial products and then offering so-called independent advisory services to customers on what are the best products,” Professor Fels said. ‘‘A second very important one is whether there should be a structural separation between traditional banking activities and the more risky investment activities,” he said, citing a 2011 report in the UK by Professor John Vickers. “Ultimately Vickers was not adopted because of vested interests in finance,” he said.

“Banks benefit from the implicit guarantee on their deposit liabilities which flows into their trading activities,” Professor Fels said. The top 250 bankers at the five largest banks earned $500m in pay and bonuses last year.

Professor Fels said a combination of factors encouraged unethical behaviour, such as customers’ poor financial literacy and weakness of competition. “But what can’t be ignored is deep structural conflict of interest between profit maximising activities and the need to provide essential services,” he said.

“Some aspects of banking are comparable to a utility, everyone needs banking services to be available, to that extent it’s an essential service.” Changes needed “careful evaluation”, “probably beyond the capacity of the royal commission to handle”.

“Some will be concerned that financial institutions face more regulation for the next five to 10 years, which will have some undesirable side effects. But it will probably have to be lived with before we can return to a more market orientated approach,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout