Blunders leave life insurers on critical list

The life insurance industry may be forced to dramatically reduce benefits, ratchet-up premiums or force exclusions on customers.

The life insurance industry may be forced to dramatically reduce benefits, ratchet up premiums or force exclusions on customers, as efforts to convince politicians to allow the sector to target workplace rehabilitation for new revenue streams look set to fail.

The industry’s efforts to overhaul laws to allow life insurers to cover medical costs in the workplace for prevention and rehabilitation of illnesses — which have been labelled as a concerning expansion in responsibility by doctors, lawyers and health insurers — are unravelling following a series of shocking revelations at the royal commission in recent days.

Over a gruelling week of hearings at Melbourne’s Federal Court, the royal commission heard Australia’s largest insurer, TAL, paid private investigators to stalk a woman with depression and anxiety as it fought her claim over an eight-year period and that the company bullied her with unnecessary and vexatious requests under threat of cancelling her policy. TAL separately tried to cancel the policy of a woman with cervical cancer by claiming she had an unrelated “history of depression”.

That followed damning evidence that Freedom Insurance staff mocked the father of a man with Down syndrome who was wrongly sold a funeral insurance plan by the predatory company and repeatedly refused his request to cancel the junk insurance.

Independent life insurer ClearView also admitted to more than 300,000 breaches of criminal anti-hawking laws when it attempted to target poorer people with policies they did not want, need or could not afford.

And CommInsure, the former life insurance arm of Commonwealth Bank, knocked back a claim from a woman who had breast cancer despite the pleadings of doctors and by relying on a two-decades old medical definition that it refused to backdate.

The company also misled the Financial Ombudsman by covering up a doctor’s advice that conflicted with its attempt to deny legitimate payouts.

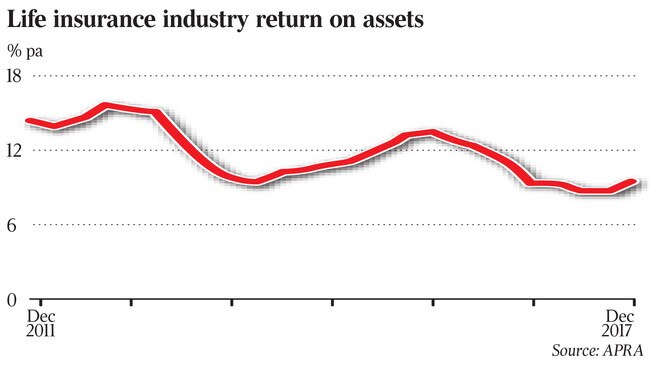

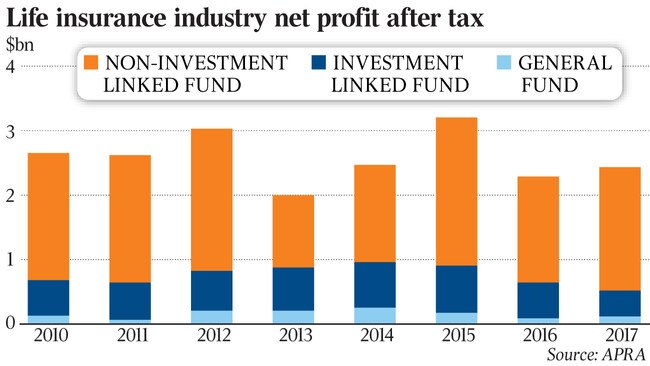

For nearly a decade, the life insurance industry has been trying to reverse years of falling profits across an array of insurance policy types, such as total and permanent disability and individual disability. Earnings have been crunched by soaring claims rates, greater awareness of the ability to claim for mental health issues and rising regulatory costs for the sector.

While some of Australia’s largest banks have thrown in the towel on the sector because they’ve found it too hard to make money, others are doubling their efforts to find a way to restore profitability to the industry.

In doing so, the sector has become increasingly interested in rehabilitation and many companies are now investing in in-house rehab resources.

Some of Australia’s largest life insurers are desperately attempting to convince a powerful Parliamentary Joint Committee to overturn laws that ban insurers from paying for treatment. They argue this could help claimants return to work early. But it would also dramatically lighten the load on the amount of money insurers would have to pay out in claims, which has concerned consumer groups and doctors.

The urgency of the sector’s lobbying has dramatically increased following this year’s federal budget proposals which clamp down on life insurance fees in superannuation — where 70 per cent of Australian are insured.

These reforms are expected to cut $3 billion a year from the life insurance sector in premiums charged to young superannuation savers, jeopardising 35 per cent of the industry’s revenue.

The Weekend Australian can reveal several members of the parliamentary committee are planning to ignore the industry’s pleadings until it adopts recommendations from an 18-month long investigation into the life insurance sector, which in March handed down nearly 50 proposals to improve shocking practices that were found to be widespread.

The inquiry was launched in the wake of revelations of poor claims handling at CommInsure, which was found to be using outdated definitions of heart attack to deny claims. Since the scandal, the committee has discovered widespread use of problematic remuneration in the industry, anti-competitive sales practices, weak consumer protections, troublesome behaviour around genetic testing and customer medical records, and a failure of self-regulation by the sector.

“We’re not going to move on workers rehabilitation until they actually get moving on the actual report. We’ve been pretty clear with the FSC on that,” one parliamentary source said.

While the sector and the Financial Services Council have argued many of the parliamentary committee proposals involve government and regulators — such as removing the industry’s exemption from parts of consumer law requiring honest and fair dealings, new regulator investigations and greater powers for financial watchdogs — it is yet to be seen whether they will independently adopt recommendations that don’t require legislative intervention.

These include getting rid of conflicted remuneration, ending the practice of cross-selling, getting legal enforcement for a strengthened code of practice, and restricting access to medical records, tightening access to genetic information and more regularly keeping up with medical opinion.

Despite being given the opportunity to prove it can self-regulate in line with the wishes of politicians and consumer groups, the life insurance sector has been reluctant to reform.

“The FSC promises to give us updates on their progress with the proposals, but we go into meetings and all they want to talk about is access to workers rehabilitation,” the source said.

Damien Mu, the chief executive of Australia’s soon-to-be-largest life insurer, AIA Group, has been directly lobbying members of the parliamentary committee and urging them to quicken the pace of worker rehabilitation reforms, despite the company giving little indication of where AIA is at on the reforms.

“Allowing private sector life insurer greater involvement in workers rehabilitation should not be linked to the government adopting the PJC’s recommendations,” AIA told the committee.

The FSC said it could not see “how any delay to the provision of enhanced rehabilitation support for consumers can be justified because the life insurance industry has not fully completed implementing the PJC recommendations”.

MLC Life Insurance CEO David Hackett said “good progress” was being made on the recommendations, but provided no detail as to what that meant.

The life insurance industry’s attempts at self-regulation have fallen well short of the requests of regulators and politicians.

The industry’s codes of practice — including one made by the FSC and another by the Insurance in Superannuation Working Group which includes the nest egg sector — were recommended to be combined into a single mandatory code enforced by the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The FSC code has not been approved by ASIC, which would give it actual regulatory teeth, while the Insurance in Superannuation Working Group code was not mandatory and unenforceable.

Berrill & Watson Lawyers insurance and superannuation principal John Berrill said the life sector should not be given any more responsibility until it shored-up its standards.

“Given the exposure of problems at the royal commission and given that there’s no external oversight of the industry code, I don’t think it’s appropriate for life insurers to have any significant role in workers rehabilitation at the moment,” Mr Berrill told The Weekend Australian.

“At the moment rehab is done through workers compensation insurers, and they are bound by really stringent codes or acts of Parliament. Life insurers are only covered by an industry code that’s not legally binding, and superannuation funds don’t have a code yet at all,” he said.

“There is an important role insurers can play, but it’s got to come with a system under which they are properly accountable for their actions and products.”

The failure of the industry to secure a victory on the workers rehabilitation front will be a blow to its plans to put an end to spiralling losses in certain policy types.

The sector is already facing pressure to cut generous benefits and gold-plated policy features for customers, as regulators and reinsurers attempt to put the industry back on sustainable footing after a prolonged period of losses.

Individual disability income insurance across the sector posted a $377 million loss in the 2016 financial year, up on a $360m after-tax loss a year earlier. More awareness of benefits has resulted in more claims, while underemployment is sparking rising levels of work-related stress. At the same time, companies are finding they are now on the hook for overly generous promises made when the policies were written during better economic times.

Premiums have surged in recent years, due to rising claims and awareness of benefits. Death and total disability cover has jumped by more than 200 per cent over the past five years, while income protection rates have doubled.

But claims experience has worsened over the past decade, particularly in disability insurance. In 2007, the insurers made a profit of 12c in the dollar on every policy. In 2013, that had deteriorated into a loss of 32c on every policy. Now policies are losing about 50c for every dollar of disability insurance policy revenue brought in.

In May this year, just a few months before ClearView Wealth chief risk officer Gregory Martin admitted his company beached criminal anti-hawking provisions more than 300,000 times at the royal commission, he told an industry conference that companies could not resort to cutting benefits or adding in more exclusions.

“We need to get on our bikes with early intervention,” Mr Martin said. “We’ll need some law changes and we need to get on with the lobbying of that.”