AMP risks $1bn super fee scandal

AMP faces the risk of a new fee scandal in its superannuation business.

AMP faces the risk of a new fee scandal in its superannuation business, as the beleaguered wealth group yesterday conceded that costs — including to repay customers in its advice business — were nearing $1 billion.

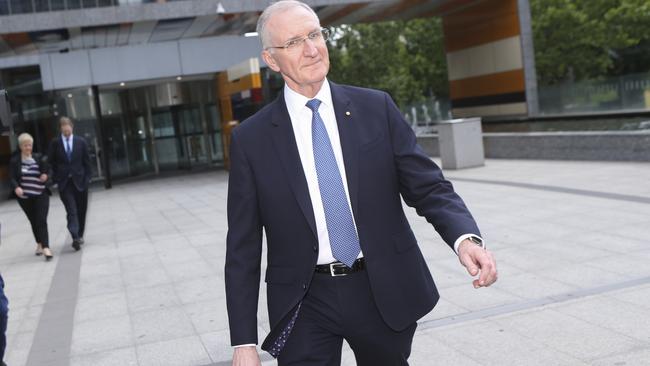

AMP’s acting chief Mike Wilkins raised the ire of senior counsel assisting Michael Hodge QC at the Hayne royal commission yesterday, as he lifted the lid on a string of AMP compliance failures and the incorrect levying of fees.

Mr Wilkins said AMP’s total cost estimate for providing customers inappropriate or no advice stood at $778m, inclusive of remediation, lost earnings, reviewing customer accounts and a range of other costs. This could cost as much as $1.18 billion if the remediation program took as much as nine years, he added.

He also agreed that for professions outside financial advice it was highly uncommon for customers to be charged fees for services they did not receive.

“It would be a normal expectation that people would understand,” Mr Wilkins said. “You would think … where a fee is charged a service would be delivered.

“AMP is on a journey in terms of what it is looking to do with its risk processes and controls.”

Mr Hodge — incredulous that it could take advisers five years to get across new regulations and realise that charging for no service was wrong — also raised eight AMP breach notifications to the corporate regulator in 2016. They related to the company’s workplace superannuation and employer plans and largely reflected small and medium businesses.

The issues potentially relate to super fund accounts that were set up before reforms were introduced in 2013 to ban general advice fees on those super products.

Mr Hodge asked: “Is the risk that AMP faces in relation to this that it may have another fees-for-no-service case on its hands?

Mr Wilkins replied: “Yes.”

He then went on to say AMP had PwC conducting a review of the conduct and potential issues in that business. “We are still going through the process of understanding this.”

An AMP spokeswoman yesterday clarified: “We are reviewing the extent to which services have been provided and, in the case of plans established prior to July 1, 2013, (and) whether remediation is required.”

AMP has been hardest hit by the fallout from the royal commission into misconduct.

The company lost its chief executive, Craig Meller, and chair Catherine Brenner earlier this year as the extent of the problems in its advice business came to light in the royal commission, and as the conduct of its board and management were called into question.

The new revelations yesterday highlight the scale of the task confronting new CEO and former Credit Suisse executive Francesco De Ferrari, who starts on December 1.

Mr Hodge also raised a more recent AMP breach notice to the Australian Securities & Investment Commissions in May, relating to the managing director of an advice firm under AMP’s licence who failed to stop charging fees where there was no adviser but ignored the edict. Mr Wilkins said that case was “immediately escalated within the advice business”.

On the broader fee-for-no-service issue, Mr Wilkins was asked why AMP had tried to dodge repaying 271,000 advice customers who were incorrectly levied amounts of less than $500 a year, before being pressed by the corporate regulator to include them in remediation.

He said AMP’s initial view was those customers were provided “general advice, rather than personal advice, and could be excluded from the process”.

In further damning statements, Mr Wilkins said AMP was yet to agree key parameters for repaying advice customers with the corporate regulator which was holding up its remediation program. He said there were two outstanding issues being debated with ASIC, including deciding on the quantum of services provided to some customers, and AMP’s proposal to collect customer testimonials confirming the receipt of services.

“I would like to finalise the agreement with ASIC. We did say that we expected that the remediation under the revised proposal would commence in the last quarter of 2018 and we are still hopeful that we will be able to begin it,” Mr Wilkins said.

Documents tendered to the royal commission showed that under a base case or worst case plan it would take AMP nine years to repay customers who received poor advice or were charged fees for no service.

AMP has ramped up its work on the program — with a team of 150 working on it — and, if an agreement is reached with ASIC, Mr Wilkins said the target was a three-year remediation program.

“Our sampling has shown that the major timeframe that there were issues were 2008 to 2015,” Mr Wilkins said, noting that despite an underinvestment in compliance nothing stood out as the “root cause” of the failings.

Mr Hodge also questioned how Mr Wilkins’ cost estimate of $778m on advice issues married up to AMP’s disclosure to the ASX that allowed for a $291m post-tax provision.

Mr Wilkins provided calculations that on a pre-tax basis the figure was $415m and the company had also flagged a $50m hit in December last year, with that latter figure recurring on a post-tax basis annually for three years.

Mr Wilkins was pushed further to admit that of $1 billion in total ongoing advice fees earned between January 2008 and June 30 last year, about 20 per cent were at risk.

Mr Hodge also highlighted data from the prudential regulator that showed AMP had a high ratio of banned advisers in the industry at 9 per cent, followed by Commonwealth Bank at 5 per cent.

He questioned whether some measures had stalled as AMP awaited the new CEO.

“A new CEO is coming into the organisation and has been given a mandate to transform the organisation,” Mr Wilkins said in response, adding that as acting boss he had made it “very clear” what behaviours were unacceptable.

He also fielded questions about pressure on AMP to cut some of its superannuation fees, which Mr Wilkins admitted were at the “upper end of an appropriate scale”.

On controversial grandfathered commissions, Mr Wilkins said AMP’s position had changed and “are now saying we favour a phased (out) approach”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout