AMP pulls back from the edge, but rough ride ahead

The company will be hoping David Murray can lead it back from the wilderness, but it will be far from easy.

On Friday, April 27, with the once-mighty AMP slipping into a spiral of chaos, the board of directors, frantic to bring the company back from the edge, resolved to bring matters to a head. Their chairman of two years, Catherine Brenner, had to go and she must be dispatched before another unpredictable week of hell could unleash itself on the staggering financial services giant.

A hastily organised phone hook-up was called for directors to discuss removing Brenner and replacing her — short-term at least — with Mike Wilkins. Wilkins was already acting chief executive after the former chief executive Craig Meller had walked the plank two weeks before.

Brenner would know she was in the death throes of her chairmanship by the time the Saturday papers hit the streets (or their online sites flashed up the night before). The Australian reported that Brenner would be ousted during a board meeting the following day, Sunday, April 29, and that Wilkins would replace her, at least temporarily.

The news report could not have been more accurate. If there was any further indication needed that Brenner’s authority had collapsed, it was this: the date and manner of the chair’s forthcoming demise had been leaked from the board — not just within hours of the discussion, but 48 hours before the execution was due to take place.

On Sunday, the board met again, a meeting that would roll into the early hours of Monday. Brenner would ultimately agree to quit, with Wilkins to stand in, pending the search for a replacement. It was a bloody coup in the manner of so many bloody AMP coups down the years.

The prospect of a new chairman led to several days of media sleuthing that added to the chaos — leaving astonished boardrooms across the country doubtless feeling they were watching an episode of Survivor. Perhaps even the regulators were shocked.

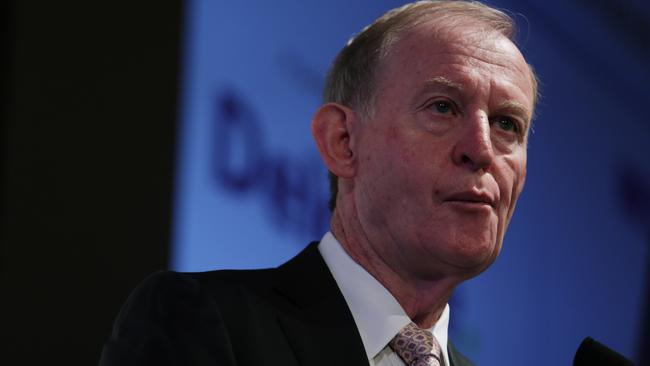

AMP yesterday added to the sense of a rolling circus by first issuing a defence against recent royal commission recommendations that the company be open to criminal charges for misleading ASIC, and then by mid-afternoon unveiling a new chairman (found in the four days after Brenner’s fall). Were it not for the calibre of the selection of David Murray to lead AMP out of the wilderness, the day could have ended in high farce. Instead, Murray’s appointment as chairman was the first in-tune note played in weeks.

By the denouement, the big regulators — the Australian Securities & Investments Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority — were advised of Brenner’s departure. The locks had been changed.

For Brenner, who had been dramatically elevated to the chairman’s suite after previous chair Simon McKeon farewelled the company at an AGM on May 12, 2016, it had been a quick two years. She was appointed chair four weeks after McKeon’s farewell at the general meeting. McKeon himself had quit after some on his board had turned on him for reasons spelled out in a 360-Degree survey — with complaints including that he lived in Melbourne.

In chairman years, Brenner’s term (and McKeon’s) were shorter than most. In AMP years this was in the zone. It was a company where hard hats were probably of more use than a club membership. AMP could chew them up and it could spit them out.

Things went badly off the rails in early April last year. AMP was a financial services giant once admired as almost a member of the family. But it received a shock that would reverberate all the way to the boardroom and would destroy the chairman and chief executive, wreak catastrophic reputational damage, leave a wounded board fighting for its life, and, as a bitter codicil, see AMP’s top lawyer tossed under a bus, almost as a sacrifice to the gods.

A year ago, give or take a week, on May 17, 2017, a senior AMP lawyer in charge of regulatory engagement was told about a clutch of internal documents; this information had made its way up from the dark midfields of the firm due to demands from corporate regulator ASIC. The documents revealed that AMP had been charging fees to unwitting customers who had received no service — in the face of internal legal advice that this practice was illegal.

The balloon went up quickly. AMP had been dealing with the regulator on this matter since 2015 and had always argued it was an administrative error. Suddenly, there was evidence that it was actually part of the business plan to rip the customers off.

The lawyer, Larissa Baker Cook, took the matter straight to the general counsel, AMP’s top in-house lawyer, Brian Salter. AMP’s external legal advisers Clayton Utz were called in. On Friday, May 19, the new head of AMP’s financial advice division, Jack Regan, was called by Salter and put in the picture. Salter and Regan immediately contacted AMP’s chief executive, Craig Meller. In turn, Meller phoned the chair, Catherine Brenner. The information raced up the line. No one was in any doubt about the potential risk to the company, not least when the regulators found out.

Over the weekend of May 20-21 — cool but sunny days ahead of winter — Salter and Brenner emailed or phoned all AMP directors to let them know what had been discovered.

Brenner, Meller, Salter, Regan, and lawyers from Clayton Utz met on Thursday, May 25. It was a week since Salter’s first call to Brenner. It was decided to immediately notify ASIC. After the meeting, Brenner phoned ASIC chair Greg Medcraft while Meller phoned ASIC deputy chair Peter Kell. The AMP chair and CEO told the two top ASIC bosses that they intended to commission an investigation and that they would share the findings with ASIC.

The offer by AMP to share with the regulator was hardly a “goodness of the heart” thing or an act of corporate collegiality. This after all was something ASIC was already investigating, sharply tightening the screws on the company for more disclosure, demanding more documents. It was ASIC’s pressure that had led to the internal malfeasance being coughed up through the system in the first place, as well as to a program already under way of paying back to customers their lost funds.

Over the next week, plans were drawn up commissioning Clayton Utz to conduct a full inquiry into what had happened — not just into the earlier fee-for-no-service which had been described as an administrative error, or the subsequent fee-for-no-service which continued against legal advice that it was illegal, but also into the reporting of these matters to ASIC.

On June 5, 2017, a formal letter of appointment with terms of reference was sent by Brenner to Clayton Utz. On behalf of the chair and the CEO, the law firm was asked to conduct an external and independent investigation.

Brenner told Clayton Utz in her covering letter that the investigation was to be “entirely independent of the business” and was commissioned exclusively by the board through herself and Meller.

But she made it a directive that Clayton Utz was to work on a “day to day” basis with Salter, Regan and other top AMP executives; it was an unsurprising directive, given that managers and staff from across the advice business would have to be contacted, interviewed and perhaps reinterviewed, with access provided to all of the internal email chains and documents that were part of the case.

“You in due course will provide Jack Regan and Brian Salter a more detailed investigation plan based on the terms of reference, including details of individuals who will be interviewed,” Brenner wrote to Clayton Utz.

“If at any stage during the course of the investigation you consider the terms of reference need to be revised, please raise this with Brian Salter and Jack Regan. Any variations to the terms of reference should be advised to me in writing by Clayton Utz.”

It was clear that Brenner the lawyer intended that Brenner the chairman would be in control.

“Clayton Utz will provide regular updates to Brian Salter and Jack Regan on the progress of the investigation,” she instructed.

There was one caveat to the instructions to Clayton Utz to work on a daily basis with Regan and Salter and it revealed Brenner’s iron hand on the tiller.

“If at any time during the investigation any issues of concern arise regarding a GLT (group leadership team) or AMP board member, Clayton Utz is to deal directly with me on any such issues.”

Salter would later be fired, in April this year, after this “day by day” communication with Clayton Utz was detailed in the royal commission. The AMP board said they had no idea Salter was in such regular contact over drafting changes with Clayton Utz. Many speculated that Salter might have been thrown out to keep the wolf from the chairman’s door.

Four months after commencing the investigation, and as winter passed to spring, Clayton Utz completed a blistering report into the wrongdoing at AMP.

There had been numerous changes to the report with back and forth between the authors and AMP. Evidence to the royal commission that there had been 25 drafts included the revelation that Brenner had requested changes in the way Craig Meller was described. If he had not been found to engage in wrongdoing, Brenner asked that the report state this clearly.

On October 4, Clayton Utz partner Nick Mavrakis had emailed Salter with a revised draft of the report that included an attachment with mark-ups showing changes that followed his discussions with Brenner.

On October 15, Salter emailed all members of the board providing marked-up updates on the report, which was scheduled for completion. The report was delivered and distributed to the AMP board for a board meeting at 7.30am on October 16.

All of this was later revealed in witness statements by AMP’s own chosen representative on the stand, Jack Regan, under questioning.

Later on October 16 last year, Brenner was determined to take the lead in delivering the damning Clayton Utz document to ASIC herself. Together with Meller, and the two executives closely involved — Regan and Salter — she met with Medcraft and Kell. Following the meeting, ASIC was given a copy of the report. How that report was described to ASIC — and whether it was portrayed as entirely independent — was a question that would come to haunt AMP.

Two days later, on October 18, Regan, Salter and the chief risk officer met with the other big regulator in town, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, to reveal what had happened and advise that ASIC had been notified and had the Clayton Utz report.

If AMP had made plans to stage-manage the shock it must have anticipated coming from the royal commission, they swiftly collapsed. Rather than a chairman emerging immediately with a comprehensive apology, there was radio silence — aside from a company spokesman.

That silence spoke louder than words. Brenner, for the duration of her remaining time as chair, would not emerge to speak on behalf of the board to shareholders and customers.

By last Friday, the royal commission had heard from counsel assisting Rowena Orr that it was open to consider criminal charges over AMP’s attempts to mislead the corporate regulator. AMP yesterday strenuously denied this.

Finally, Mike Wilkins, standing in as chairman as well as CEO, spoke where Brenner had faltered: “Appropriate steps are being taken to address the issues raised, and remediating our customers is being given utmost priority.

“On behalf of the board, I reiterate our sincerest apology to our customers, and know we have significant work to do to rebuild their trust.”

If anything more needs to be added it is perhaps that AMP directors could double check the expiry dates on any employment insurance in the bottom drawer. Whatever lies ahead will be far from a smooth ride.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout