Small farmers take on the ‘carbon cowboys’ in battle to reduce emissions

Farmers are banding together to try and cash in on government grants for carbon trading and avoid the growing numbers of ‘carbon cowboys’ seeking to rip them off.

For lamb producer Andrew Ferrier the idea of finding a way to take pressure off his stocking rates during droughts and amid wildly fluctuating lamb prices is a no-brainer. In theory, the federal government’s Clean Energy Regulator scheme for monetising reduced greenhouse emissions, through not clearing land or storing CO2 in soil, would be a perfect fit for farmers who are either already aiming to become net zero carbon emitters or looking for that trigger to push them into action.

“If we can get an income stream that we call ‘off-farm’ then it’s going to take the pressure off stocking rates during droughts and fluctuation of commodity prices,” says Ferrier. “Once it’s set, it’s there for 25 years and you can see what the income is going to be over that period.”

The promise is huge for farmers. The market is already worth about $600m and counting, and rural giant Elders believes it will become “mainstream” for farmers looking to diversify their earnings.

Australia’s biggest corporates need to hit 40 per cent carbon reduction targets by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, and farmers who are kicking a number of other carbon-friendly goals can sell them government-certified Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs). It could and should be a win-win.

And perhaps it is for the large scale operators: AACo, which accounts for 1 per cent of the nation’s landmass, uses the Beef Cattle Herd Management Method to claim ACCUs by improving beef cattle maturity and quality, and is looking into other options.

Rupert Murdoch’s son in-law Alasdair MacLeod has sold $1m of soil carbon credits to Microsoft through the private market. He focuses on soil sequestration. MacLeod chairs Atlas Carbon, which advises farmers of the complex process of obtaining carbon credits.

Small farmers hit

But for smaller farmers who might run 8000 acres the complexity of achieving accreditation and the costs are considerable. That dilemma has spurred a new breed of “carbon cowboys” who approach farmers with costly carbon schemes that never deliver returns. This has led Ferrier to band together with a bunch of like-minded farmers from southern Queensland (his farm is west of Stanthorpe and east of Texas) who first worked together about 30 years ago as the Traprock Woolgrowers Association.

They encouraged the creation of Regen Farmers Mutual, believed to be the country’s first farmer-led co-operative set up to work on carbon initiatives and biodiversity projects.

Regen is now working with about 80 small farmers and hopes to eventually sell $100m of ACCUs by 2030. It’s no small change.

Regen has already agreed to sell the first 1000 ACCUs from the Traprock project to the charity Carbon 4 Good for $100 per unit, which is above the current trading price for standard ACCUs of about $35 per unit and above the $50 per unit being received for so-called Indigenous Savanna projects.

Those ACCUs received a premium above the $50 per unit price Regen hopes to receive for the rest of its carbon because they are from the farmer’s already created Traprock biodiversity corridor and will be extinguished rather than used for any offsetting purpose.

The farmers involved in the Traprock project will receive an upfront payment of about 60 per cent for their ACCUs when they receive accreditation for their reforestation project, with the rest of the funds delivered annuity-style over the remaining 24 years.

“It’s a good cash injection,” says Ferrier, who led the group of farmers who banded together to create the co-op.

Complex regulation

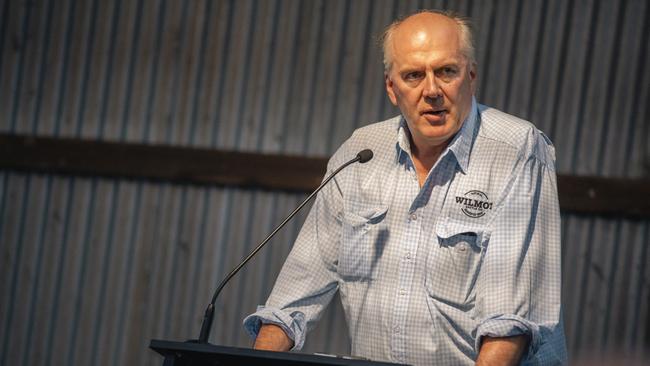

The fact that farmers are needing to find like-minded peers or tap the likes of MacLeod is a sign, though, that the Clean Energy Regulator is not quite fit for purpose, according to Regen co-founder Andrew Ward.

The ACCU system was independently reviewed earlier this year and found to be sound, but Ward believes that program was set up for the benefit of the oil, gas and coal industries who needed to “show” they were meeting targets, rather than farmers who were able to provide solutions.

“If you think about the environment in which the Clean Energy Regulator was established, they didn’t even believe in climate change,” says Ward, citing the coalition government which came to power shortly after it was formed. “The Clean Energy Regulator was more about working with the energy industry than the agriculture and vegetation industries.”

Ward, the son of the late Bruce Ward whose Colly Farms was the first cotton producer to be listed on the ASX, says that a lot of farmers, used to dealing with the Department of Agriculture, struggle to engage with its framework.

“A lot of farmers have felt this market wasn’t designed for them, and it’s really difficult to get into … it’s very expensive and time-consuming,” he explains.

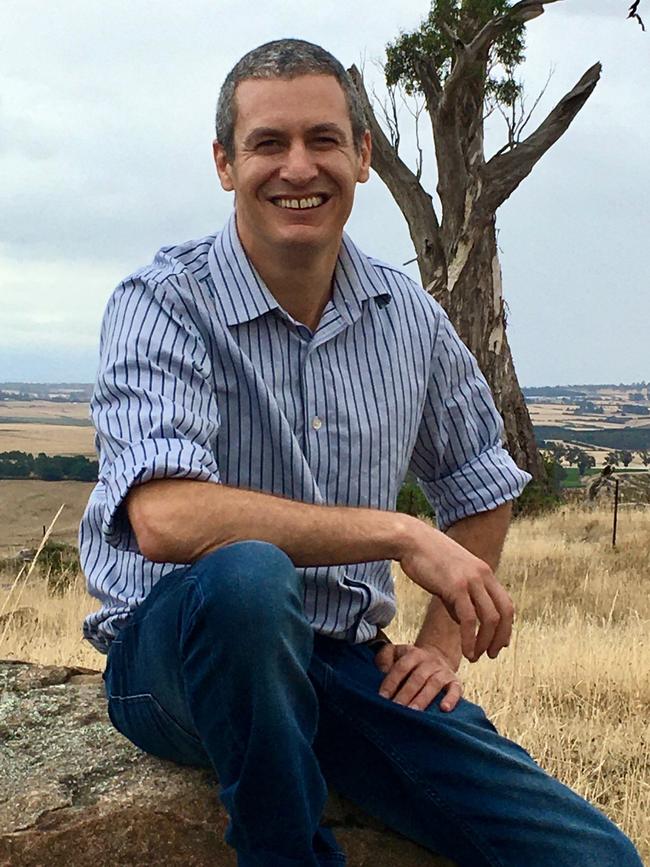

It’s a view backed up by farmer Andrew Findlay, who runs a wool, lamb and fruit property and was part of the initial Traprock Woolgrowers Association that tried to offset plummeting wool prices in the 1990s with efforts to market a biodiversity-friendly wool instead.

Findlay describes himself as adept at managing government submissions but found the work around mapping that was required by the Clean Energy Regulator beyond his technical capability.

“I certainly don’t think it was written for farmers,” says Findlay. “I don’t know too many farmers who could actually do that geospatial imaging work that’s required by the Clean Energy Regulator.”

Findlay is now part of the Regen co-operative, which he hopes will achieve biodiversity credits for his farm as well as certifying his property for ACCUs. Regen is seeking to raise $6m in funding to expand its projects.

Rural giant Elders is also leaning into the carbon market and has just signed a joint venture with Carbon Fix to help farmers overcome barriers limiting farmers’ in the “emerging” carbon market, such as product knowledge, trust in service providers, and the cost to establish a project.

“We see carbon farming becoming mainstream,” says Carbon Fix founder Nigel Kuzemko. “The great benefit of carbon farming is that it can add an extra revenue stream to the farm which is linked to a different commodity that the current products.”

Mr Kuzemko is particularly focused on Soil Carbon projects that Carbon Fix sees as the “cherry on top” of a farming operation.

“Those techniques used for increasing carbon also encourage grass growth and so increases weight gain and carrying capacity,” Mr Kuzemko said.

New regulations

There are millions of taxpayer dollars at stake across the various state and federal carbon and biodiversity schemes, and Mr Ward fears there soon could be further regulatory hurdles.

Greenwashing is in the federal government’s spotlight, particularly in light of global concerns about carbon credits being issued that may not be providing any actual net benefit.

The Albanese government is currently reviewing the Nature Repair Market, which incentivises land restoration and encourage nature positive land management practices.

“I am very anxious about the Nature Repair Market because they are worried about greenwashing rather than adoption,” says Ward.

He believes this will lead to a focus on land that is pristine, rather than farming land that farmers need to repair and regenerate.

“What they’ll do is put together a method that will have more rigour, and it will probably be for a pristine environment that they have heaps of data, which is not what we need. We need regeneration of degraded land, so when you are talking about nature repair you actually need methods that can be widely adopted by farmers that genuinely improve the environment.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout