The keys which will decide Chris Dawson’s fate

Chris Dawson is relying on evidence lost to time and witnesses who have died in his desperate bid to be freed, after he was found guilty of his wife’s murder.

Chris Dawson has argued that he ought to be released from prison owing to bank statements and hospital records lost to time, and friends who had died over the last four decades who were unable to give their version of events in his defence, a court has heard this week.

Dawson, 75, sits in Clarence Correctional Centre, just outside of Grafton, where he is serving his prison sentence after he was in August 2022 jailed for the murder of his wife Lynette.

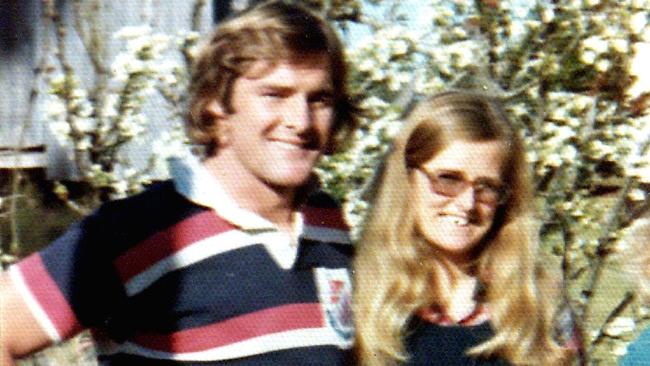

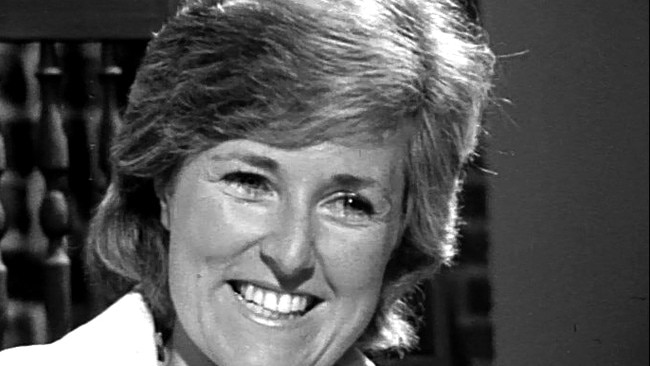

Lynette Simms vanished from her family’s Bayview home on Sydney’s northern beaches in January 1982 in what has become one of the country’s most famous missing persons’ cases.

In the days after she vanished, Dawson moved his teenage lover – a former student and the family’s babysitter – into his Gilwinga Drive address.

Nearly two years ago, Supreme Court Justice Ian Harrison found Dawson killed his wife to have “unfettered access” to the young woman, JC.

After being sentenced to 24 years in prison, and told that he will likely die in jail, Dawson has launched an appeal against the verdict.

In the Court of Criminal Appeal in Sydney this week, Dawson’s counsel, Senior Public Defender Belinda Rigg SC, argued that Justice Harrison’s verdict was “unreasonable” and was subject to a “miscarriage of justice”.

The three judge panel which will decide Dawson’s fate - Justices Julie Ward, Anthony Payne and Christine Adamson - have reserved their decision to be handed down at a later date.

FOUR DECADES

Dawson has appealed his verdict on five grounds including that he suffered a “significant forensic disadvantage” due to being unable to call evidence or witnesses due to the extraordinary delay between Lynette’s disappearance and the start of his trial in May 2022.

This is despite that in his judgment Justice Harrison noted: “I must remain constantly vigilant to identify and make allowance for the possibility that Mr Dawson’s ability adequately to respond to the Crown case may have been unfairly compromised by the fact that he faces a trial for murder in 2022 and not 1982.”

During the trial, Dawson’s legal team was unable to call several pieces of evidence including employment records at Rockcastle Private Hospital.

The Dawsons’ former Bayview neighbours, Peter and Jill Breese, said they had both independently seen Ms Simms working at Rockcastle Hospital at Curl Curl in June 1984 – over two-and-a-half years after she was last seen.

His legal team was also unable to provide copies of Lynette’s bank card statements.

The court heard during the trial that Dawson previously said that when he received her statements - following her disappearance - they indicated purchases on January 12 and February 27.

Dawson, having claimed that Lynette walked out on him and their two children, after he dropped her off at a Mona Vale bus stop on the morning of January 9, 1982, argued it could not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that she was not still alive that afternoon.

They also argued it could not be proven that Dawson did not receive a phone call from Lynette that afternoon while he was working at the Northbridge Baths as a lifeguard.

Phillip Day, a Dawson family friend who was present at the Northbridge Baths that afternoon, was unable to be called because he died before the trial began.

He gave a statement to police in February 2001 in which he saw Dawson was summoned to the pool office for a telephone call.

“When he returned he advised (Lynette’s mother) Helena (Simms) and me that the call was from Lyn, who was going away for a few days ‘to sort herself out’,” he said.

He also gave evidence at a 2003 inquest.

Ms Rigg told the court this week that there was nothing “sinister” about Mr Day’s presence at the pool, despite the Crown prosecution at trial claiming that Dawson had “cunningly” arranged for him to be there along with his mother in law.

THE UNAVAILABLE WITNESSES

A central feature of Dawson’s defence was several claimed sightings of Ms Simms after her disappearance.

One of those came from Sue Butlin, who died in May 1988, who said she saw Ms Simms while working a weekend job at a fruit and vegetable shop at Kulnura on the Central Coast.

Ray Butlin – a Dawson family friend – told the court during the trial that his former wife had told him of seeing Ms Simms at the roadside fruit barn sometime after her disappearance.

“The substance was that (Ms Butlin) saw a person that she believed was Lyn Dawson,” Mr Butlin said during the trial.

“She walked towards her and the woman proceeded, without turning around, and got into a car and drove off.”

Ms Rigg described Ms Butlin’s claim as “quite extraordinary”.

“That’s a very clear example of a deceased person whose evidence was crucial,” Ms Rigg said.

THE PILLARS

Crown prosecutor Brett Hatfield described Dawson’s version of events as being “glaringly improbable”.

“There is not a significant possibility that an innocent person has been convicted in this case,” Mr Hatfield said.

Mr Hatfield referred to what he described as the “11 pillars” of evidence which had proven the circumstantial case against Mr Dawson.

He pointed to the fact that Ms Simms never had any contact with any person after January 8, 1982 when she spoke to her mother on the phone.

That included her family, friends, colleagues and children, who she “adored”, Mr Hatfield said.

He said it was “inherently unlikely” that she would have voluntarily abandoned her family - including the husband she “idolised” and her children given her struggles to conceive.

He further said she would not have cut off communication with her parents and her siblings, even if she had left Dawson.

The court heard during the trial that Ms Simms and Mr Dawson left a marriage counselling session on the afternoon of January 8, 1982 hand-in-hand.

Mr Dawson later told detectives - in his only interview with police - that they were planning a “sexy celebration” that evening.

But no one ever heard from her again after that night.

Mr Hatfield argued Ms Simms was committed to her marriage despite it deteriorating in 1981 when she became aware that Dawson had cheated on her with JC.

“If she wasn’t leaving when those other things occurred, why would she leave when it was looking better after the counselling?” Mr Hatfield said.

He also said that Dawson had made attempts to leave Ms Simms, including attempting to move to Queensland with JC and start a new life just before Christmas 1981.

He said that Dawson had refused to accept JC’s attempt to break off their relationship before she left to holiday at South West Rocks in early 1982.

Mr Hatfield told the court that after his wife disappeared, Dawson conducted himself in a manner which was “completely irreconcilable with any purported belief that (Ms Simms) was alive and might return home.”

This included moving JC into their home, where she slept in the matrimonial bed, and allowing her to go through Ms Dawson’s clothing and jewellery.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW

The three judges will now weigh up the merits of the appeal and have reserved their judgment.

Should they find that Dawson was subject to a miscarriage of justice, they could then either order a retrial or quash his conviction entirely.

They will hand down their decision at a later date.