How Australia’s park of the future could charge your phone, give wi-fi and monitor the BBQ from the palm of your hand

Australia’s park of the future, which can be controlled from the palm of your hand, has been revealed after a trial site was opened in a lush community estate.

Australia’s park of the future – which can charge your phone, give you free wi-fi, remotely control the public barbecue and even tell you when plants need to be watered – has been revealed.

The architects of the National Broadband Network (NBN) recently commissioned research showing their outdoor fibre connections could more than triple by the next decade – and they want Australians to take full advantage.

The first of these trial “smart places” has been unveiled in Western Australia.

Essentially, government and private business could fund the development of a Smart Place through NBN Co, allowing “eligible non-premises locations” to tap into the network in the great outdoors.

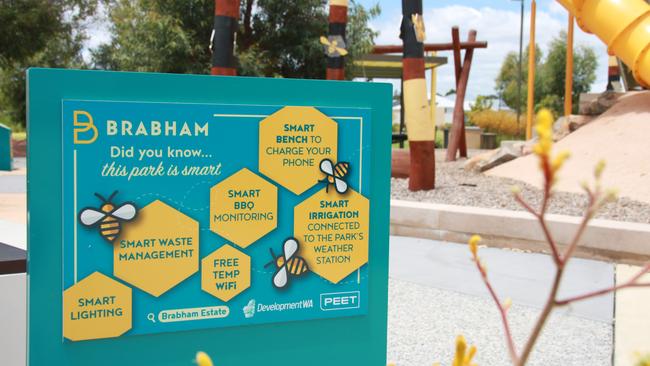

Peet’s Brabham Estate, located in the Perth suburb of Brabham, about 21km northeast of the CBD, is a housing development nestled among a collective of several other similar developments on the WA capital’s fringes, with one major difference.

The estate’s Honeycomb Park has access to NBN fibre technology that not only provides park users with high-speed wi-fi but also powers park benches that can charge smartphones or connect a weather station to the irrigation system, telling it when it’s the best time to water the plants.

“This is a game changer for governments, developers, utilities and transport industries – it gives them the power of fibre just about anywhere,” head of NBN new developments Andrew Walsh said.

“Smart communities developer Peet used NBN Smart Places to deliver, via retail providers, high performance wi-fi to the community park, allowing connectivity, smart benches with phone chargers, and a weather station which decides when to mow the lawns.

“We’ve only scratched the surface of its potential applications – and the emergence of AI as the next big thing in tech will generate many more ways for NBN Smart Places to connect smart cities and towns across Australia.”

Honeycomb Park is visually impressive, with a large central playground resembling a beehive, native plants, and artworks as well as amenities you’d expect to find down at the local park.

And while not everything there is up and running at this stage, it’s an ambitious project.

For example, community barbecues will in the future become network-enabled, allowing monitoring from a smartphone.

The lighting within the park is also smart, only coming on when it’s needed, and a toilet block automatically locks its doors overnight.

The smart benches charge a phone wirelessly if it’s left on a marked spot on the bench, although it also has USB ports in the event you happened to remember to bring the right cable.

And as mentioned previously, the weather station communicates with the irrigation system to provide optimal watering.

Signage in the park also boasts of “smart waste management,” although it’s unclear what this entails.

Mr Walsh said the device used to connect the Smart Places to the network was “small, but (its) impact is massive”.

“It can provide the connectivity to monitor and control traffic light signals, digital billboards, provide wi-fi in public places and provide real-time high-definition CCTV coverage,” he said.

“A smart place (or smart cities as they’re often known) integrates technology into the surrounding built or natural environment to increase liveability, sustainability and productivity for residents and businesses.”

The uptake could be slow going, though. A University of South Australia questionnaire in January found 45 per cent of respondents had never heard of smart cities and 54 per cent didn’t understand the term.

The UniSA researchers said the questionnaire “underlines the failure of local governments to explain the value of the smart city concept to residents despite large amounts of money spent on promotional campaigns”.

“Judging by the survey feedback we received, the SA government and local councils are not achieving cut-through in explaining the concept,” lead researcher Shadi Shayan said.

“Residents are at the core of any smart city and the fact that more than 50 per cent of people are unfamiliar with the term poses a serious issue for authorities.”

Of course, the eventual transition to smart cities isn’t without its critics.

Advocacy groups like Privacy International warn the technology could turn our cities into “increasingly surveilled space, where there is no longer such a thing as strolling anonymously down the streets”.

Statements on their website warn smart cities risk our privacy and our democracy, with the potential for our personal data, including our facial biometrics captured on CCTV, to be sold off to governments and the private sector.

“Moreover, the smart cities we have observed have so far been reflecting already existing inequalities: built for the wealthier and for those with access to technology; they have failed to include disfranchised populations, the less-abled and to address the issue of gender inequality in cities,” Privacy International’s website reads.

NBN Co began taking orders for non-premises connections in June.