How Chris Dawson’s web of lies unravelled 40 years after murdering his wife

Chris Dawson constructed a web of lies about the disappearance of his wife Lynette, but his deceit finally came undone during the murder trial.

Chris Dawson lied about receiving several phone calls from his wife in the days and weeks after she went missing amid an attempt to deflect attention about her murder, a judge has found.

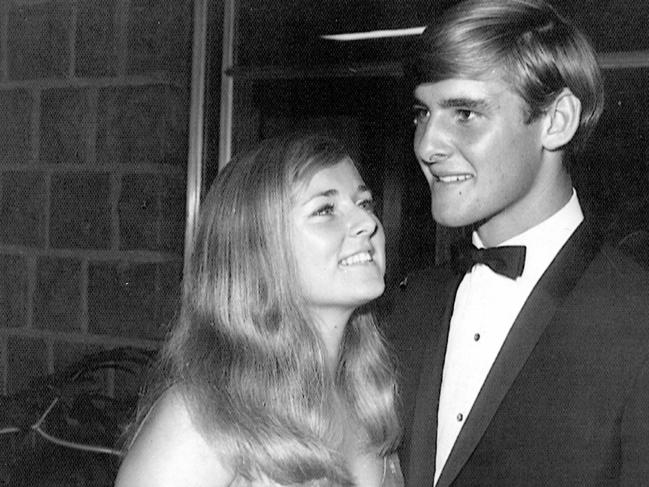

The former Newtown Jets rugby league player and teacher is on Tuesday night in jail after he was convicted by Supreme Court Justice Ian Harrison of killing his wife Lynette and disposing of her body in 1982.

Following a judge-alone trial earlier this year, Justice Harrison found that Dawson lied for four decades to cover up the murder of Ms Dawson, who vanished without ever speaking to her family, children, friends and colleagues ever again.

During his trial, Dawson claimed that his wife voluntarily walked out on their idyllic existence on Sydney’s northern beaches.

However, Justice Harrison found that evidence of her strong bond with her children was “completely at odds with the proposition” that she voluntarily left her home.

He also found it was unlikely she would have taken off without so much as a change of underwear.

One of the key planks of Dawson’s defence was his claim that Ms Dawson contacted him on several occasions after she disappeared.

In his police interview in Queensland in 1991, Dawson admitted it was “extremely strange” that she only contacted him and not any of her family or friends.

According to Dawson’s version of events, he first received a phone call from his wife at the Northbridge Baths on the afternoon of January 9, 1982.

He claimed he dropped her off at a Mona Vale bus stop earlier that day before she called him at his part-time lifeguard job to say she needed time away.

“The following few weeks I had similar phone calls from Lyn, more STD calls saying that she needed extra time,” Dawson told police in his 1991 interview.

But Justice Ian Harrison described Dawson’s descriptions of the phone calls as “lacking in context” and “pregnant with cliche”.

He also said it was doubtful that a woman who had decided to flee her home would only contact the man who was responsible for her departure.

He said Dawson’s report of receiving a phone call at the Northbridge Baths on the afternoon of January 9, 1982 was a “lie”.

He said his version of events was contradicted by the diary of a girl who worked at the baths who said the pool’s owner was not present on that day.

“I am satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that Lynette Dawson never telephoned Mr Dawson after 8 January, 1982,” Justice Harrison said.

“That reinforces other circumstantial evidence that leads me to conclude that Lynette Dawson did not leave her home voluntarily.”

Justice Ian Harrison found that Dawson displayed a “consciousness of guilt” by making several false statements about the circumstances around Ms Dawson’s disappearance.

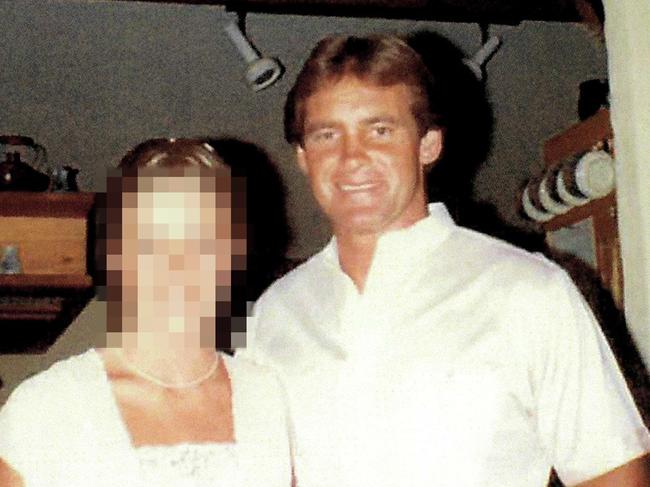

Central to the case was JC, Dawson’s former student and babysitter, who moved into his family’s Gilwinga Drive home after Ms Dawson went missing.

Early in 1982, JC travelled to South West Rocks to holiday with family and friends.

JC told the court that during one phone call, Dawson told her: “Lyn’s gone, she’s not coming back.”

The court was told that days after Ms Dawson disappeared, Dawson drove to the NSW Mid North Coast to pick up the young woman and brought her back to his matrimonial Bayview home.

However, in his 1991 police interview, he stated: “I thought she was going to return to her family home, not to my home. She ended up coming and living with me because she wasn’t wanted anywhere else.”

Justice Harrison found that Dawson lied about her moving in with her family and that JC arrived immediately at Gilwinga Drive, where they resumed their “energetic sexual relationship”.

Justice Harrison also found that Dawson lied about his motivation for travelling to South West Rocks, having claimed it was JC who wanted to leave.

During his marathon 4½ hour decision on Tuesday, Justice Harrison also found that Dawson lied about the events in his family home on the evening of January 8, 1982.

In his police interview, Dawson told detectives: “The day prior to Lyn leaving, there was an incident at home where she had thrown our little … our second daughter onto the bed and sort of had a bit of an emotional breakdown at the time.”

But Justice Harrison listed that as one of several lies told by Dawson in an attempt to “deflect” attention away from him having murdered his wife.