Chris Dawson’s murder appeal case attacked as ‘glaringly improbable’

Chris Dawson’s version of events surrounding his wife’s disappearance has been described as “glaringly improbable” by prosecutors.

Chris Dawson’s version of events surrounding his wife’s disappearance has been attacked as “glaringly improbable” and implausible, as three judges weigh up whether to quash his murder conviction.

For the last three days Dawson has watched via videolink from a cell at Clarence Correctional Centre as his legal team appeared before the state’s highest court - the Court of Criminal Appeal - in an attempt to overturn his guilty verdict.

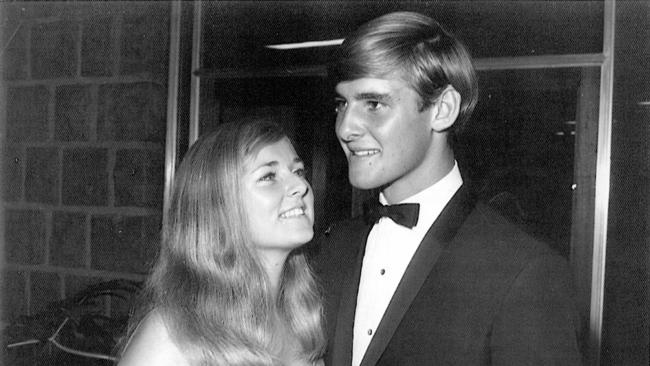

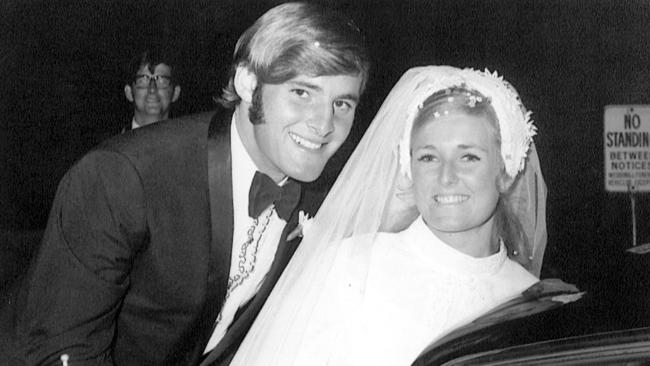

The former Newtown Jets star and ex-teacher, 75, was in August 2022 jailed for the murder of his wife Lynette Simms over 40 years ago.

Ms Simms, a mother-of-two, disappeared from her family’s Bayview home on January 8, 1982.

Her body has never been found and she has not contacted her friends and family.

Dawson has claimed that Ms Simms voluntarily abandoned their family and he received a series of phone calls from her after she was last seen on January 8, 1982.

Dawson’s barrister, senior public defender Belinda Rigg SC, told the court that his conviction ought to be quashed because of the unavailability of key evidence and witnesses which have been lost over the past 40 years.

Justice Ian Harrison found Dawson guilty of murder and that he was driven by a “possessive infatuation” with one of his teenage students, JC.

Following the three-day hearing, Justices Julie Ward, Anthony Payne and Christine Adamson on Wednesday afternoon reserved their decision which will be handed down at a later date.

‘GLARINGLY IMPROBABLE’

Dawson has appealed the verdict on five grounds, including that Justice Harrison found that a series of lies pointed to him displaying a consciousness of guilt.

Justice Harrison, in his judgment, said Dawson had lied about his relationship with JC, about wanting to resume his relationship with his wife and about receiving phone calls from her after her disappearance.

Ms Rigg has argued that the consciousness of guilty argument was not relied upon by the Crown prosecution at trial.

The three judges overseeing the appeal must weigh up whether Dawson was subject to a miscarriage of justice.

Justice Adamson on Wednesday put questions to Crown prosecutor Brett Hatfield about what the court should do if it identifies error with Justice Harrison’s reasoning relating to the consciousness of guilt finding.

“Do you say the strength of the Crown case, irrespective of what the trial judge did, was so great that it reduced the defence case to a fanciful hypothesis. And therefore there’s no point putting everyone through it again?” Justice Adamson asked.

“Yes, we do say that,” Mr Hatfield replied.

Mr Hatfield said any error would be a “defect of process or reasoning” and would not affect the credibility of the Crown case.

“This is a case that his version of events is so glaringly improbable,” Mr Hatfield said.

He pointed to what he described as the “11 pillars” of the Crown case and argued that “the implausibility of the applicant’s account is patent when it’s scrutinised”.

THE BABYSITTER

Dawson’s legal team raised criticisms about the reliability of the evidence of JC, who appeared as the Crown’s star witness.

In particular, they pointed to her claim at trial that Dawson told her on one occasion that he contemplated hiring a hitman to kill his wife.

During her evidence, JC told the court that on one occasion she travelled with Dawson to a building somewhere south of the Harbour Bridge.

She said she stayed in the car while he went inside and when he returned he said he went to hire a hitman to “kill Lyn” but decided against it.

“I think I asked him, ‘what was that about because we’re going and it doesn’t seem like we’ve done anything’,” JC said during her evidence.

“He said, ‘I went inside to get a hitman to kill Lyn, but then I decided I couldn’t do it because innocent people would be killed, would be hurt’.”

Justice Harrison, in his judgment, rejected the claim, saying it was “improbable in the extreme” that he would make such an admission to a young girl such as JC.

However, Justice Adamson on Wednesday argued that a majority of JC’s testimony was supported by other evidence, including love notes which Dawson left in her school bag.

“She was very, very significantly corroborated on pretty much everything that mattered,” Justice Adamson said.

“Except the hitman, which was rejected.”

THE ARTIST

During the Dawson trial, artist Kristin Hardiman told the court that Ms Simms had in November 1981 commissioned a portrait of her two daughters.

Ms Hardiman said she came to the Dawson home on Gilwinga Drive and photographed the children.

However, Ms Hardiman told the court that when she phoned the Dawson home in mid-January 1982, she was told by Dawson that Ms Simms had “gone away” and didn’t “want them anymore”.

Separately, the court was told that Dawson claimed he received a phone call from Ms Simms on the afternoon of January 9, 1982 saying she needed time away.

Dawson also claimed that he received further phone calls from Ms Simms on January 10 and 15, the court was told.

The Crown prosecution pointed to Ms Hardiman’s evidence as proof of Ms Simms’ strong bond to her children, arguing that she would not have abandoned them.

“These are matters that do not sit comfortably or consistently with a voluntary decision to abandon her family without notice,” Justice Harrison wrote in his judgment in August 2022.

In court on Wednesday, Crown prosecutor Brett Hatfield told the court that Dawson’s reaction to the artist was “odd behaviour”.

“Not only the reaction of the applicant for the complete lack of sentiment towards his own children but a complete lack of regard for the young artist … Your Honours might think a desire to quickly shut down any matter relating to his wife at that time,” Mr Hardiman said.

“It seems to me to be odd that he knows she doesn’t want them anymore … This is at a stage when he’s telling people he thinks she’s coming back,” Justice Julie Ward told the court.

THE PHONE CALL

During a 1991 police interview, Dawson told detectives he dropped his wife off at a Mona Vale bus stop on the morning of January 9 and she failed to meet him later that afternoon at the Northbridge Baths, where he worked as a part-time lifeguard.

Dawson told police while at work he received a long-distance phone call from his wife saying that she needed time away.

He also said that he received subsequent phone calls from Ms Simms before she eventually said she was leaving him.

One woman, who worked at the Northbridge Baths as a teen, told the court during the trial that she recalled on one occasion in the summer of 1981-82 picking up a long-distance call, and a female on the other end asked to speak to either Chris Dawson or his brother Paul.

Crown prosecutor Brett Hatfield told the court on Tuesday that there could have been a call — but it could not have been from Ms Simms, who he said was killed either late on January 8 or early January 9.

“The phone, we would submit, there could have been a call … that it was the (Ms Simms) on the other end of the phone is a lie, a deliberate lie,” Mr Hatfield said.

Ms Rigg earlier told the court it could not be established beyond a reasonable doubt that Ms Simms did not make the phone call.

Justice Julie Ward — one of three judges hearing the appeal — on Tuesday noted the only evidence about the phone call coming from Ms Simms was from Dawson.

ELEVEN PILLARS

On day two of the three-day hearing before the Court of Criminal Appeal, Mr Hatfield outlined what he described as 11 “pillars” of the case that he said reinforced Dawson’s guilt.

“There is not a significant possibility that an innocent person has been convicted in this case,” Mr Hatfield said.

Mr Hatfield said the first “pillar” which led to Dawson’s conviction was the fact that Ms Simms never spoke to or had contact with any person after January 8, 1982.

Secondly, he said, it was “inherently unlikely” she would have “voluntarily abandoned the husband she idolised” and the “children she adored”.

Particularly, he pointed to Ms Simms’ effort to have children, which included undergoing a fertility procedure.

Mr Hatfield’s third point was she would not have cut off communication with her parents and her siblings even if she had left Dawson.

He also said at the time Ms Simms disappeared, Dawson was attempting to establish a “public, permanent, long-term partnership” with JC, including asking her to marry him and attending her school formal as her date.

Fifthly, Mr Hatfield said, Ms Simms was committed to her marriage despite it deteriorating in 1981 when she became aware Dawson had cheated on her.

“If she wasn’t leaving when those other things occurred, why would she leave when it was looking better after the counselling?” Mr Hatfield said.

Mr Hatfield also pointed to what he described as the “atmosphere” of Dawson’s relationship with JC, which he said was “marked by a degree of desperation and obsession”.

He said, in his seventh point, Dawson had made attempts to leave Ms Simms, including attempting to move to Queensland, planning to move into a North Manly flat with JC and attempting to sell his home.

According to his eighth point, he said Dawson had refused to accept JC’s attempt to break off their relationship before she left to holiday at South West Rocks.

He also said Dawson was the last person to see Ms Simms alive and had the “opportunity and motive” to kill her on January 8 and 9, 1982.

In his 10th point, Mr Hatfield said after Dawson’s wife disappeared, he conducted himself in a manner that was “completely irreconcilable with any purported belief that (Ms Simms) was alive and might return home.”

This included moving JC into his home, where she slept in the matrimonial bed, and allowing her to go through Ms Simms’ clothing and jewellery.

Lastly, Mr Hatfield said there was no evidence of Ms Simms being alive despite proof of life checks during a missing person’s probe and three separate police investigations.

Dawson was sentenced to 24 years in prison, with an 18-year non-parole period, after Justice Harrison found him guilty of murder.

Last year, Dawson was also convicted of one count of carnal knowledge after a judge found he engaged in sexual activities with one of his students at a Sydney high school in 1980.

He was sentenced by Judge Sarah Huggett to three years in jail and had one year added onto his non-parole period.

His non-parole period is due to expire in August 2041, by which time he will be 93 years old.

New “no body, no parole” laws passed by NSW parliament – dubbed “Lyn’s law” – mean that Dawson will not be paroled until he reveals where Ms Simms is buried.