Story of NGA’s Cham Padmapani statue is shrouded in secrecy

The National Gallery of Australia is facing questions over the dubious provenance of a Cham bronze statue of the Buddhist Bodhisattva Padmapani after a string of valuable antiquities has been forfeited in recent years.

The 12 months to June 2012 was a golden period at Canberra’s National Gallery of Australia.

The nation’s youngest capital city art gallery was booming thanks to a program of annual blockbuster European art exhibitions such as the record-setting Masterpieces from Paris, from the Musee d’Orsay, which was so popular it necessitated the introduction of timed ticketing.

The gallery’s board included Australia’s wealthiest benefactors. Donations from board trustees and their connections, coupled with steady federal funding, was fuelling rapid collecting for the NGA, which around this time finally eclipsed the esteemed National Gallery of Victoria in total financial value.

That year, chief trustee Tim Fairfax, scion of the media dynasty, spent his own money acquiring a rare beige silk-screen by Henri Matisse. It joined the gallery’s collection, having been bought directly from the French impressionist’s descendants.

Fairfax’s sister, Sally White, and her husband Geoffrey contributed to the $US1.5m work which the NGA’s director at the time, Ron Radford, described as “perhaps the most extraordinary work acquired this year” — a collection of three “ninth to 10th-century gilt bronze sculptures made by the Cham people of Vietnam”.

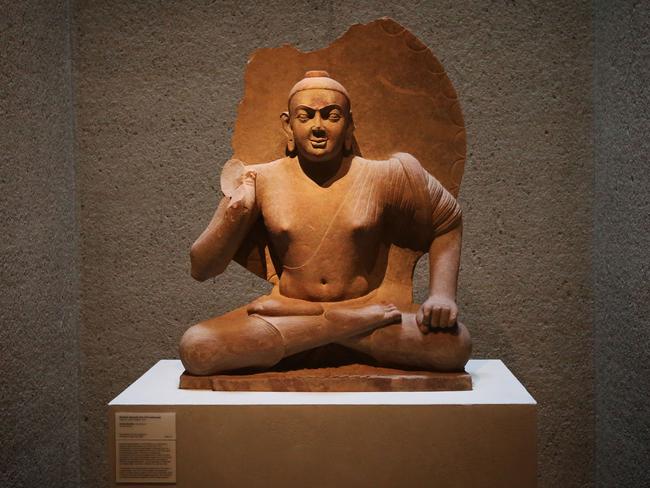

The 50cm tall bronze Padmapani and two smaller attendants in the same style “are among the few outside Vietnam”, Radford wrote in the 2012 annual report.

In Buddhism, Padmapani is recognised as the Luminous Lord of Infinite Compassion; the Dalai Lama is the contemporary living incarnation of this most revered entity.

“The (group of sculptures) brings focus and prestige to the collection — a needed focus for our small Vietnamese collection and prestige to our large Southeast Asian collection,” Radford wrote.

This particular figure, with its elaborate halo and extensive gilding, is described on the NGA’s website as “the finest and most intact Cham bronze known”.

But since 2016 this remarkable Padmapani has not been on display. A note on the gallery’s website reveals its status is in limbo. “The supplied chain of ownership for this object is being reviewed and further research is under way,” it reads.

However, The Australian recently has located a book published in 2011 — before the NGA bought the Padmapani — wherein John Guy, one of the world authorities on Southeast Asian antiquities, states that the artefact was likely looted and was owned by dealer Douglas Latchford.

The book The Cham of Vietnam clearly attributes the group of Cham Buddhist figures to the “Douglas Latchford Collection, London”. In the volume Guy, curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, also wrote: “A number of copper-alloy cast images representing Bodhisattvas have recently come to light, their provenances are unclear but it must be assumed they were recovered by illicit diggers.”

Latchford was charged with wire fraud, smuggling and conspiracy by US prosecutors in an indictment brought before a New York court in 2019. Extraordinarily, the NGA has a copy of the book, The Cham of Vietnam, in its collection.

Tess Davis, executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, the world’s foremost organisation combating cultural racketeering, tells The Australian: “Any object associated with Douglas Latchford should be considered a conflict antiquity until proven otherwise.

“Latchford was the mastermind of an infamous criminal network, which plundered countless masterpieces from the war zones of Southeast Asia and trafficked them into the art world’s top collections. Since 2012 he was in the crosshairs of American prosecutors, and he died last year under a felony indictment fighting extradition to New York.

“His customers can no longer feign plausible deniability. The NGA and the many other museums with Latchford’s loot have now had years to do the right thing. Any objects with any ties to him should have long been treated as stolen property until proven otherwise. The link to him alone should have sounded every alarm.”

Last week CNN reported that the late dealer’s daughter, Nawapan Kriangsak, has promised to return all of the Cambodian artefacts — at least 100 statues and carvings — she inherited from her father.

The collection is considered of such cultural significance that the country’s national museum in Phnom Penh is being expanded to accommodate it.

The NGA will not confirm it bought the statues from Latchford.

Indeed, the gallery refuses to disclose who sold the statues. Its website stated that the statues were with a “private collector in Hong Kong since the early 1970s, then with another private collector in London who sold it to the NGA”, before the Hong Kong reference was recently removed.

Asked if the NGA became aware of doubts over the legitimacy of the Padmapani’s provenance after Guy revealed the past owner, it has said that it acquired the book some weeks after the artefact was added to its collection.

In a statement to The Australian the NGA says it is now committed to ethical and transparent collecting but it continues to be bound to a deed of secrecy signed when it purchased the Padmapani.

“While we would not enter into any such agreement again, we must abide by the past agreement, including in relation to the release of information on past owners as understood at the time of acquisition.

“To date the deed of confidentiality has not been an impediment to our research.”

University of Sydney law school adjunct professor Duncan Chappell, a member of the National Cultural Heritage Committee that advises the federal government on antiquity issues, says the statement is evidence the NGA isn’t doing enough.

The NGA first went into damage control about its Asian antiquity collection not long after the purchase of the Padmapani — when it was found in possession of a stolen Dancing Shiva from India bought for $US5m.

Despite a change of leadership at the top of the gallery in Canberra twice since that time, more than 2000 antiquities in the NGA’s collection remain under review — although the gallery says this is a matter of “due diligence” and denies that all items have povenance issues.

Chappell says “such important objects were being acquired, how they appeared out of the blue should have raised red flags”.

“Clearly the gallery was seeking to make itself a central repository of important trinkets from our region, but by their very nature they should have been exercising extreme caution with due diligence,” he says.

The Padmapani was added to a small list of very precious items under specific review in 2015 and has been on the priority list since then.

Chappell says he has never heard of an art museum agreeing to secrecy when buying artworks, and adhering to it now defies best practice. “Our pre-eminent gallery is concealing something potentially unlawful,” he says. “I’d have thought the last thing the NGA would be doing is concealing purchase information from the public.

“This is opaque and the opposite of a transparent commitment to ensuring good provenance.”

Chappell has been observing the NGA’s Asian antiquity collection for many years.

Just a few weeks before Radford’s annual report boast about the Padmapani was tabled in parliament in September 2012, Australia’s temple of high art was jointly identified by US Homeland Security and India’s Idol Wing antiquity crimes unit as the recipient of a major stolen artefact from India, the aforementioned Dancing Shiva.

Those claims were carried in media reports in India, the US and Australia, with the result the NGA has struggled ever since with the reputational damage of being a voracious purchaser of stolen and potentially stolen antiquities.

![Chola dynasty Tamil Nadu, India Shiva as Lord of the Dance [Nataraja] 11th-12th century bronze, purchased in 2008 and returned to India in 2014.](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/ba7b462954ede0a5d06a7517d7580981?width=650)

The Dancing Shiva was one of the most expensive artworks owned by an Australian gallery. It cost $US5m. The statue was returned to India in 2014 with great fanfare and no compensation by Tony Abbott, the prime minister at the time, after compelling evidence emerged of it having been hacked from a southern Indian temple and taken away in the middle of the night just a few months before it was sold to the NGA.

The Dancing Shiva was the first of four forfeited items the NGA acquired from disgraced New York dealer Subhash Kapoor, who is languishing on remand in India and is wanted in the US, described as the mastermind of one of the largest illicit trafficking operations in the world.

US Homeland Security has linked more than 2000 Asian antiquities to Kapoor, who sold and gave artworks to galleries and private collectors for 40 years until his arrest.

The most recent planned handover from the NGA, of a pair of door guardians bought from Kapoor, occurred in December 2019 when they were returned to India. They are now with the Archaeological Survey of India. A ceremonial handover was deferred after Scott Morrison’s trip to India last year was postponed owing to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Indian government has requested the return of a further three antiquities the NGA bought from Kapoor, but for years their cases have not been publicly updated.

The NGA during its golden acquisitive years had been in the habit of accepting at face value photocopied statements claiming items had been in various prestigious collections for many years before their acquisition.

For the items returned to India, these documents were found to have been created by Kapoor’s staff and, unable to establish a chain of ownership outside India before 1970 or produce compelling evidence to the contrary, the gallery eventually admitted it did not have legitimate title to the pieces.

The antiquities forfeited by the NGA so far were all acquired from Kapoor. There is one exception so far — a huge 2000-year old stone Buddha, which The Australian revealed in 2014 had been bought from a different New York dealer, Nancy Wiener.

That Buddha also was returned to India, in 2015, but because Wiener was still living in New York the NGA successfully called in its refund guarantee on the million-dollar purchase.

After it cashed the refund, gallery investigators looked no further. Had they done so they might have learned about Latchford.

It was he who had sold it to Wiener.

“The NGA’s behaviour is negligent at best and an affront to both the Vietnamese people and Australian taxpayers,” Davis says.

“It’s also incredibly damaging to the legitimate art market, which is already struggling against growing accusations of antiquities trafficking, money laundering and even terrorist financing.”

Latchford died in August last year, six months after federal prosecutors in New York accused him of trafficking in looted Cambodian relics and falsifying documents in a case now been abandoned because of his death.

Arguably, the NGA could have used its experience with the Nancy Wiener Buddha, and Guy’s claim the Padmapani was discovered by illicit diggers, to request a refund on White’s Padmapani purchase.

NGA director Nick Mitzevich disagrees. He says an NGA curator met Guy in New York in 2019 as part of inquiries into the provenance of the artefact, and there was no conclusive evidence the statues were looted.

“It’s pure speculation, that doesn’t mean we’re disqualifying it, we’re gathering evidence and working through that evidence,” Mitzevich says.

A gallery spokeswoman says the NGA has not contacted the Vietnam consulate or its equivalent art gallery in Vietnam.

Michaela Boland has written about stolen antiquities for The Australian since 2012, culminating in a chapter published in The Palgrave Handbook on Art Crime (2019), the most comprehensive, international collection of research on art crime.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout