Feared and Revered exhibition opens at the National Museum of Australia

A new exhibition seeks to challenge our perceptions of women, power, gender and desire – turning the ancient into a very modern topic.

On the ancient Acropolis in Athens, from the fifth century BCE onwards, there were two particularly distinctive images of the goddess Athena on display. Neither has survived and we know them only from ancient replicas and descriptions. But, even so, they can tell us a lot about representing a deity. One, a masterpiece by the Greek sculptor Pheidias, was housed in the Parthenon, the famous temple completed in the 430s BCE. This Athena, built on a superhuman scale, was constructed around a wooden frame, cleverly covered in gold and ivory. The goddess stood more than 10m tall, dressed in a glittering helmet and long tunic, holding a spear and a shield. (A full-sized replica in Nashville, Tennessee is probably the best guide to her original appearance.)

The other image was smaller and older, and had originally belonged to a temple destroyed in the war between the Greeks and Persians in the early fifth century BCE. It was preserved just next door to the Parthenon in a smaller shrine, known as the Erechtheion, where it was lovingly tended, adorned with jewels and dressed in a specially woven gown, but underneath it was nothing more than a plank of olive wood, which – so legend claimed – had miraculously fallen to earth from heaven. The central scene of the sculpted frieze of the Parthenon depicts the presentation of a new gown (or peplos) to clothe that bare, but very sacred, bit of wood.

The difference between these two images was not simply a matter of aesthetic styles or fashion, or of the distinction between the primitive plank and the more sophisticated construction in gold and ivory. What was at stake were two completely different ideas of how to represent the goddess and her divine power. The sculpture in the Parthenon was made by the ingenious hand of a great artist, at enormous expense and on a vast scale: a dazzling Athena, in the most precious materials, and in the form of a human female warrior, towering over the mortals who came to admire or worship her. The other image, by contrast, expressed sacredness by its very refusal to ape human form, or to depend on the skill of any human artist. The power of the plank resided not in its size or material preciousness, but in its origins in heaven itself.

This pair of “statues” – if you can call a plank a statue – points to some of the key questions raised in the Feared and Revered: Feminine Power Through the Ages exhibition at the National Museum of Australia.

What does the image of a goddess amount to? How have people through time, and across the world, imagined divine power, particularly female divine power? How have they represented it to themselves? How have they questioned, challenged, worshipped or rejected it? What stories have they told to explain it? Where have they drawn the boundary between feminine and masculine power, or between the power for good and the power for bad?

The aim has not been to search out forgotten mother goddesses, or to uncover traces of a lost world in which, once upon a time, women ruled in heaven and on earth. The myth of matriarchy is exactly that: a myth. The aim is much more to show how questions of sex, gender and desire have always been inseparable from ideas of divine power, and how puzzling, unsettling and relevant those questions still are.

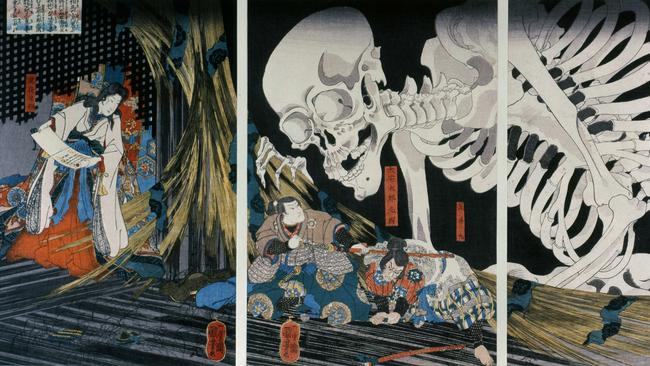

The exhibition and its accompanying book ask us to look hard at some of the most arresting images ever made, and to reflect on their meanings and ambiguities. There are no simple answers or straightforwardly “right” interpretations. The paintings and sculptures of the many-handed, bloodstained Hindu goddess, Kali, for example, trampling on the body of her husband Shiva point, for some observers, to a story of destruction and the dangerous power of the woman, for others to a lesson in liberation and the goddess’s fearless transcendence of death.

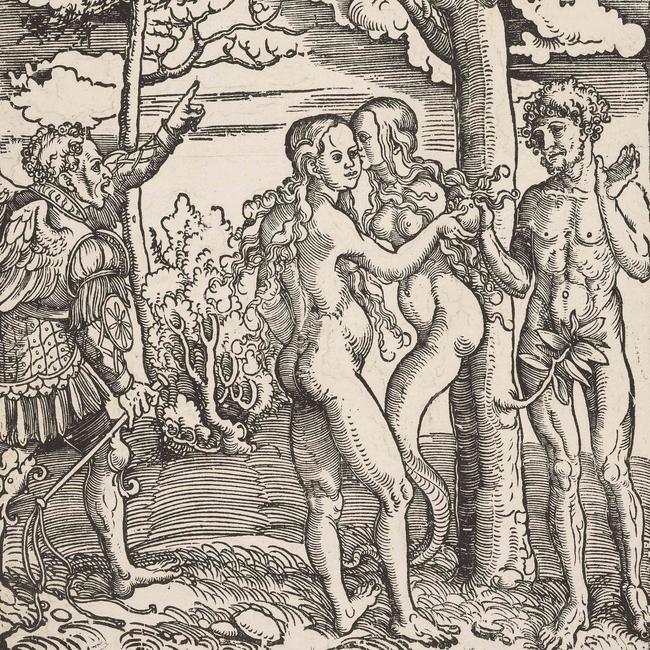

The figure of Eve in the Garden of Eden, eating the apple and offering it to Adam, is regularly taken to signal “woman as temptress”, responsible for the sins of mankind; but in some mystical traditions, she has been presented as a seeker after “Knowledge” (from whose tree the apple was plucked).

Or take the severed head of Medusa from Greek and Roman art and myth, which destroyed anyone who looked at it. How should she best be depicted? Usually, we see her as a monstrous creature, with snakes for her hair and an oversized protruding tongue, as if her destructive power lay in her capacity to shock and repel. But an alternative artistic tradition makes her a beautiful young woman, as if that power lay instead in her capacity to seduce. How far, to push that further, should we see sexual desire as a superhuman force that risks destroying the “civilised” order of the world?

At the same time the exhibition prompts us to look again at some images that Western culture now takes too much for granted. The naked image of the goddess Aphrodite or Venus – and there are rows and rows of them in museums across the world – has become so far removed from any idea of divine power that it can seem almost banal in its apparently conservative classicism.

Here we get the chance to rediscover the danger in these images, and to see just how destabilising they were when they were first produced: not banal at all, but sensationally provocative.

That is vividly captured in a chilling anecdote about the first ever full-sized (“human-sized”, that is) statue of Aphrodite, made by the fourth-century BCE sculptor Praxiteles, and – though again the original does not survive – the ancestor of most of those we now see lining museum walls. Housed in a temple to the goddess in the city of Knidos, on what is now the Turkish coast, it had the capacity to turn men mad. On one occasion, it was said, a young man contrived to be locked up in the temple all night, made love to the statue (the traces of his ejaculation were supposed to have been still visible on its thigh centuries later) and the next morning threw himself off a cliff. Part of the moral here lies in the perils of confusing inanimate marble with flesh and blood. But the story underlines the destructive power of the “goddess of love” (or perhaps we should better call her, in a less romantic way, the “goddess of sex” or “of desire”). Her statues are dangerous things.

The exhibition also shines a spotlight on the idea of the “feminine” itself, as well as on the idea of “power”, raising in the process some sharp questions about gender boundaries. The case of Athena already headlines these issues. The goddess lay somewhere between female and male, for, though born a woman, she was – as Pheidias’s statue demonstrates – equipped with martial attributes that fundamentally conflict with Greek concepts of female gender. Apart from the subversive, mythical Amazons, Greek women were not warriors. And Athena was not even brought into the world by a mother but directly from the head of her father, Zeus.

This kind of fluidity of gender is a prominent feature throughout the exhibition, seen in ancient Mesopotamia, for example (where the goddess Inanna could be described as both a woman and a man), and most dramatically in the art of the 19th-century Luba kingdom, in the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Here figures of secular and spiritual power can be represented with breasts and male genitalia, and sacred images may present a non-binary aspect. It is as if the divine sphere, and its representations, offer a space where binary gender norms of the human world can be debated and challenged. That could hardly be more topical.

Indeed, this is a very topical exhibition. Some of the works of art on display go back almost five millennia. But many of their themes are still part of our own cultural debate and artistic repertoire worldwide. I am thinking here of the performances of actor and singer Beyoncé Knowles, riffing on the famous statue of the Greek goddess of Victory in the Louvre (and at the same time challenging its “whiteness” and its power).

And I’m thinking of the continued use of images of the severed head of Medusa to undermine women’s prestige (some infamous propaganda in the 2016 US election campaign featured Donald Trump holding the dripping head of Hillary Clinton).

But my own particular favourite is Kiki Smith’s Lilith – the ancient demon, best known for destroying babies, who was said to be the first wife of Adam and to have been expelled from the Garden of Eden for disobedience. From the 19th century, she began to be reclaimed as a symbol of female defiance. Smith’s sculpture of 1994 reclaims her better than any other. Lilith is naked, but not displaying herself to us; she’s fixing those who look at her with her steely blue eyes; and she’s a free spirit, upside down on the wall, defying gravity. Feminine power undiluted.

Mary Beard’s essay appears in the publication Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic ($59.95, 272pp). Feared and Revered: Feminine Power Through the Ages is at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, until August 27, 2023.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout