Charles Blackman, the literary humanist

Charles Blackman was not only a much celebrated painter but also exceedingly prolific.

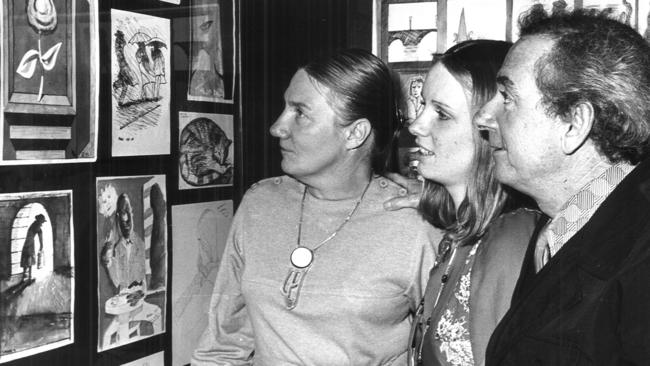

Charles Blackman was not only a much celebrated painter but also exceedingly prolific. On both counts his immortality is assured. His remarkable contribution to Australian art was recognised publicly in the huge retrospective exhibition Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls and Angels at the National Gallery of Victoria, which travelled around Australia in 1993-94.

That exhibition coincided with the making of the documentary film Charles Blackman: Dreams and Shadows, of which Blackman himself somehow became the star. Always articulate and variously poetic, reflective, comical and crazy, Blackman revealed in the film some of the emotional intensity that underpins his art. His performance, in the company of the narration of Barry Humphries, captured the duality of fact and fantasy, or indeed surreality, of his art and life. But his profound and unaffected humanity more than anything else struck viewers.

English journalist John Pringle, writing in Britain’s The Observer in 1961, described Blackman’s humanism as “emotional and honest, compassionate but tough (and) rooted in the working class from which he comes”. Although no doubt partly true, the class cap never really fitted this mercurial self-made artist.

Blackman was an avowed individualist and his art is strongly autobiographical. He was opposed to social realism and to politics in the art world, the latter demonstrated in his gesture in 1975 of cutting up a painting on the front page of The Australian, smiling as he did it, with the caption: “I love my country. Party politics is cutting it in half.”

Blackman’s individualism was of a linking rather than a separating kind, on the Dostoyevskian model (like that of Arthur Boyd) — based on the idea of developing oneself to the utmost so as to communicate to the greatest number.

His subjects were accordingly humanist and drawn from everyday visual and emotional experience: seeing schoolgirls walking through the streets and lanes on the way to and from school, for instance; or sharing his wife’s bewilderment as her eyesight deteriorated and her pregnant body changed shape, as in the Alice in Wonderland series.

These everyday autobiographical subjects were then universalised through expansion into their full range of emotional and imaginative possibilities, largely through reading relevantly to that experience.

The vividness of Blackman’s reading was related to his need during his 27-year marriage to Barbara, a writer and child psychologist, to read aloud, making it a shared experience.

“Reading out loud,” he told an ABC interviewer, “is a different sort of experience to reading to oneself, because the savouring of the words and the slowing down of the pace allows images to hang in the air.”

Blackman was extremely well and widely read and he had an enviable recall for passages and verses by his favourite writers. Among these were the French symbolist poets and novelists — Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Gide, Alain-Fournier, Colette and others — from whom he assimilated his romantic vision of the artist and his belief that intuition is the highest form of intelligence.

There are echoes throughout his work of the adolescent eroticism of these mainly autobiographical writers. Alain-Fournier’s quest for ideal love in The Lost Domain is a recurrent theme, just as the perversely innocent novels of Colette became his lifelong inspiration.

Another of Blackman’s favourites was Australian lyricist John Shaw Neilson, whose ineffable poem Schoolgirls Hastening was reproduced in the catalogue of his first solo exhibition in Melbourne at the Peter Bray Gallery in 1953. Neilson’s bid to “touch the Unknowable Divine” or to fix “the moment of love entering” was, equally, Blackman’s own.

Blackman’s discovery of books on modern art and literature was also his means to self-education. This was directly responsible for his decision to give up his early promising career as a press artist at the Sydney Sun and take to the road in search of art and artist’s studios.

He moved to Brisbane in 1948 and linked with the young Barjai group of poets, Barrie Reid, Laurie Collinson and Barbara Patterson, who was soon to become his wife. Barbara’s ordered writer’s mind deepened his experience of literature, and her friendship with Judith Wright opened a door into the world where people were actively painting, writing and thinking.

Paradoxically for one who was to become Australia’s outstanding literary painter, Blackman was brought up in a household with no books and where reading was regarded as “a waste of time”.

Charles was the third child and only boy in a family of girls, whose father shot through when Charles was four. Aside from his father’s ability to engineer models and his mother’s reputed inability to distinguish between imagination and reality, there was no art in his background.

The legacy of his upbringing was, as he often said, a unique insight into the language of the emotions, above all the female psyche and feelings of guilt, fear, sexuality and violence. A preoccupation with the feminine was indeed the thread running through his work, connecting and explaining its psychological inwardness, fragile beauty, sense of loss and vulnerability. This predominantly feminine sensibility was contained within a very masculine personality, and it was this combination of opposites — of intimate subject matter and anonymity of facture — that gave his work its extraordinary tension.

Blackman’s drawing began with his mere outlining of Ginger Meggs cartoons; yet his draughtsmanship is now admired for its vigorous attack, purity of line and delicate contrasts of intense blacks, middle greys and brilliant whites.

A fellow art cadet at the Sun remembers him drawing “as if he were the other half of a duel and the paper had a rapier of its own”. Blackman liked to quote a remark by John Brack that the emotions in his pictures looked as if they had been carved with an axe.

His best drawings, and there are legions of them, are widely regarded as among the finest ever produced in this country. These drawings are mostly independent creations but in the second half of his career they also became integral to his paintings.

Blackman’s formative years as a painter were spent in Melbourne whither he was attracted in 1951 by a sense of kinship with the painters and poets in the Heide Circle and with John Perceval and the Boyds at Murrumbeena.

He was at once the successor to the Angry Penguins artists, especially Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester and Danila Vassilieff, and a catalyst to the creative upsurge of the 50s.

His surfeit of restless energy contributed directly to the collaborative mood that engendered Mirka Mora’s studio, resuscitated the Contemporary Art Society and culminated in the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art and Design. Charles went on to become the ingenue of the Antipodeans, arguably dominating their single historic exhibition with his wall of pictures of child-women holding bouquets.

Within this fertile competitive environment, Blackman discovered his major theme in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, painting the Carrollean story as a personal and collaborative fairytale. While each painting is improvised and complete unto itself, their sequence corresponds with an arc evolution, an unfolding life cycle, a kind of mirror to the absurd logic of Alice’s adventures. With its inquiring heroine, luminous colour and witty wordplay, the series of Alice paintings was conceived as a response to Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings (so enamoured of the Reeds), as their feminine counterpoint, no more or less.

Long separated from one another, often in private collections, these Alice in Wonderland paintings were reunited by the National Gallery of Victoria in a 2006 blockbuster exhibition. Charles was there to witness his eldest son Auguste, the child in the real Alice’s womb, open the show.

In 1961, launched with his family to London via the coveted Helena Rubinstein Travelling Scholarship (the richest prize for an Australian artist, worth £1300) and a sellout exhibition in Brisbane, Blackman was taken up by distinguished figures in the art world.

He was represented in landmark exhibitions of Australian art in London at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1961 and the Tate Gallery in 1963. He had a successful one-man show at the prestigious Matthiesen Gallery and represented Australia (with Brett Whiteley and Lawrence Daws) at the Biennale des Jeunes in Paris.

His work, based on the intimacies of family life, acquired a deeper resonance through contact with European galleries, contemporary literature and theatre; his interview on the BBC’s Third program in 1965 with literary critic Al Alvarez was judged interview of the year; while the Blackman apartment was a lively centre for expatriates as well as for British poets and intellectuals.

Blackman’s reputation peaked on his return to Australia, as did his income, which, after half a lifetime of real poverty, he enjoyed. Yet for the first time he found himself isolated artistically. He settled in Sydney, where his mythic figural paintings, often of bathers or picnickers, came under increasing pressure from the artistic fashion for formalist abstraction.

A new studio led to large garden paintings and in turn to designing for tapestries and a year in Paris. He found new forms for his art, such as printmaking, but apart from a temporary comeback with his passionate nightmare paintings in the late 70s, his work was increasingly sidelined by the demise of lyricism.

The nightmare series was an end as well as a beginning. Living in Buderim with his second wife, 30 years younger, released his innate romanticism. Fathering two more children, he painted the dream — virgins and waterfalls in his Garden of Eden rainforest. The rainforest turned into a cathedral with allusions to the music of Debussy. This rekindling of his interest in a synthesis between the arts was realised most fully perhaps in his theatrical work, such as his sets for the West Australian Ballet production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Fame was not a friend to Blackman. In hindsight one can see that his private world came into collision with public demands, with repercussions that led to the progressive alcoholism that ultimately destroyed his capacity, health and freedom.

He said towards the end that his paintings were a tribute to his belief in the gift of life. Death never interested him. Like the shady moggy cats that slunk through his charcoal drawings (and he fed at Kings Cross), he was so well known and he is no longer there.

Charles Raymond Blackman is survived by his three former wives — Barbara Blackman, Genevieve de Couvreur and Victoria Bowers — and children Auguste, Christabel, Barnaby, Beatrice (Bertie), Felix and Axiom.

During his last years he was lovingly supported by his children and his minders.

Felicity St John Moore was curator of Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls and Angels at the National Gallery of Victoria and co-curator of Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout