UAP Brisbane is making Lindy Lee’s sculpture Ouroboros for the National Gallery of Australia

Come behind the scenes at a Brisbane foundry where artist Lindy Lee is working on Ouroboros, her $14m project for the National Gallery of Australia.

Lindy Lee’s Ouroboros is still two years from being installed at the National Gallery of Australia, but it’s possible to walk around and even inside a version of the monumental sculpture in its embryonic form.

At a foundry in Brisbane this month I pulled on a set of electronic goggles and gripped a pair of handsets as I walked around a full-scale virtual-reality model of the sculpture.

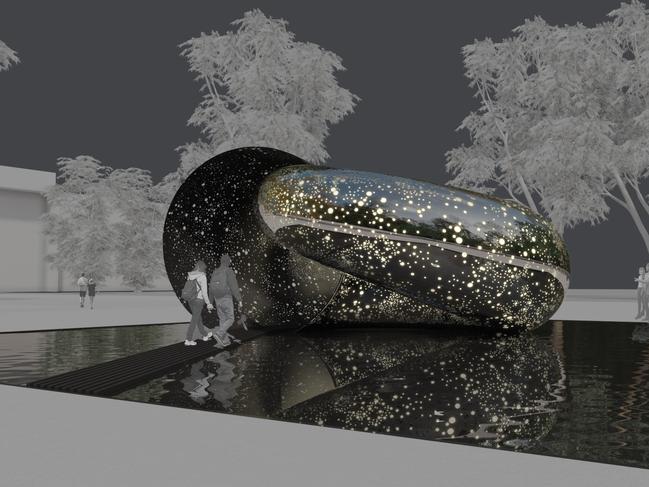

When complete, Ouroboros will be surrounded by a pool of water, giving the impression it is floating or somehow suspended in space. With the goggles on, I walked across the (virtual) water to the shiny structure – an enormous curved cone with the pointy end tucked inside. I stepped into its mouth where it was suddenly dark, but with light shining through the myriad holes in the surface.

Ouroboros may be the most technically advanced artwork yet attempted in Australia. Lee was commissioned by Nick Mitzevich, director of the National Gallery of Australia, to make something extraordinary to commemorate the gallery’s 40th anniversary this year. It takes the form of an ouroboros – the ancient symbol of a snake eating its tail, representing eternal rebirth – and when complete in 2024 it will take up residence close to the gallery’s entry on King Edward Terrace in Canberra.

The project was announced in September last year and attracted as much attention for its hefty price tag, $14m, as for its unusual and ambitious form.

What the VR Ouroboros cannot capture is the beautiful sensory experience Lee intends – the highly polished stainless-steel surface that will reflect its surroundings in daylight and then, at night, the inner illumination that will transform the solid sculpture into a constellation of stars.

“I know intellectually how it works because I’ve made a number of perforated works before,” Lee says. “But I can’t know at that scale what’s going to happen when you walk inside, as the sunlight filters in through those perforations.

“That’s a piece of magic that has to happen in the real world – you can’t manufacture that.”

I’m speaking to Lee in a glass-walled meeting room at UAP, the Brisbane-based company that has become a world leader in the specialised business of art fabrication. On the factory floor are other iterations of Ouroboros: a 1:2-scale maquette Lee and her assistants have made in polystyrene foam; and a full-size prototype segment, cast in steel and about 4m in diameter, that looks like a sliced-off piece of aircraft fuselage.

In the meeting room, Lee sits on an office chair with her legs folded on the seat – a pose not unlike the one Tony Costa captured in his Archibald Prize-winning portrait of her. Lee practises meditation and Zen, and her discussion about Ouroboros and her other artworks takes on a metaphysical bent as she describes sculptural forms that are suggestive of matter forming and dissolving, or of the universe pulsing in and out.

Abstractions aside, the job of taking Ouroboros from idea to three dimensions has demanded enormous skill and expertise. Being a one-off piece, its components are being designed for the first time, hence the level of experimentation, engineering and expense.

Ouroboros belongs to a series of work Lee calls The Life of Stars, named for the first sculpture installed in Shanghai in 2015, and a second that was installed outside the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Other works in the series have a similar appearance with organic shapes, mirror-like finish and patterns of perforation, but Ouroboros is at another level. Some of the earlier pieces were constructed from panel-beaten stainless steel and have an internal structure. So that Ouroboros can be self-supporting, and large enough to walk into, it needs to be made from cast stainless steel 9mm thick.

To meet this technical challenge, UAP recently has installed – with assistance from a state government industry grant – an induction furnace able to heat to 1680C. Ouroboros will be made in about 240 separate panels, the perforations hand-cut by skilled artisans with plasma torches, and then trucked to Canberra for welding and installation.

UAP’s general manager, Amanda Harris, shows me around the foundry and explains the various processes involved, from the polystyrene maquette, to the cope and drag moulds, and cast steel panels that are yet to be polished.

Ouroboros is intended to be a sustainable sculpture – like the symbol of rebirth itself, it will be made from recycled stainless steel – and Harris shows me a bin filled with thin blades of shiny silver metal.

About 13 tonnes will be needed to make Ouroboros, the composition of each batch to be checked in a spectrometer reading to ensure its consistency as 316 stainless steel, similar to surgical or marine-grade.

At a dinner for supporters of the Ouroboros project, UAP gave a demonstration of a bronze casting. The spectators stood well back behind a glass screen, as two foundry workers used a crane to lift a crucible of molten bronze and poured it into moulds. A process as old as the Bronze Age (as early as 3200BC) doesn’t fail to astonish, as the red-hot metal glows with fierce intensity.

UAP, formerly known as Urban Art Projects, was founded by brothers Matthew and Daniel Tobin in 1993. They started with a small foundry in Brisbane and now have operations and projects around the world. UAP’s fabrication expertise can be seen in projects such as the Wahat Al Karama monument in the United Arab Emirates, an edition of Louise Bourgeois’s giant spider, Maman, and Place of the Eels, an inverted stainless-steel bus in Parramatta by artists Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro. The company recently purchased a fine-art foundry in New York, Polich Tallix, whose collaborators have included Roy Lichtenstein, Richard Serra and Jeff Koons.

Ouroboros is a demonstration of the sophisticated, symbiotic relationship between an artist and a fabrication company.

Lee first encountered UAP when she met Daniel at a party and Matthew later helped install a piece of hers in Shanghai. “All I knew was they were identical twins who bought a backyard foundry,” she says. “I had no idea.”

Soon came an invitation for Lee to visit the foundry in Brisbane and to let her imagination run wild. With UAP she produced her first public sculpture, The Garden of Cloud and Stone, for Sydney’s Chinatown, and UAP allowed her to experiment with “flung” bronze technique, making sculptural compositions from carefully poured pools of molten metal.

Her work has been shown from the US to Hong Kong and Japan, and several of her major sculptures have been installed in China. As well as Ouroboros, she has two other new projects in Australia: One Bright Pearl, a spherical sculpture for the Woollahra Gallery in Sydney, and a large piece called Being Swallowed By the Milky Way, for the Queen’s Wharf development in Brisbane.

How did she arrive at the idea for her Life of Stars sculptures and Ouroboros? Lee’s seriousness about art can obscure her sense of fun and leg-pulling humour. She makes like Robert De Niro’s character in Casino when she says, “I’m waitin’, it’s gonna come, I’m waitin’ for a thought”.

Several things happened. Her practice of piercing and burning paper and sheet metal began to suggest to her three-dimensionality; then she landed on the perfect form of an egg.

“It is the universal shape, it’s in every culture,” she says. “I often choose very symmetrical things, really strong shapes, and I want to make it disintegrate – so that it fluctuates between solidity and dissolution. The more I do, the more I know that’s what it’s about.”

She describes her artistic practice as driven by curiosity, but also of letting go and allowing ideas to simply come.

“It happens because you’re engaged in something, and your engagement triggers curiosity, and that curiosity takes you somewhere,” she says.

“The more engaged you are, the more present you are, you let go of yourself – you’ve got nothing to do with it – and the more the ideas come.

“I don’t know how to say this without sounding a bit wacky. There’s always a path, even if you don’t know there’s a path. And it’s only in retrospect that you see that you’ve been making a path.”

Daniel Tobin says fabrication of Ouroboros is a high-risk venture, even for an outfit as experienced as UAP. As part of its risk assessment for the project, the company consulted other foundries that might be able to take on some of the work.

“All of those stainless-steel foundries, their business model is based on repetition and production line,” Tobin says.

“They have been saying no, no, no. This is a bespoke work that requires time, a highly skilled workforce and a repeatable technique to deliver a seamless finish on a highly complex object. It is what it is.”

At $14m, Ouroboros may yet have met its match. An outdoor installation by Jonathan Jones for the new Sydney Modern gallery, opening next week, also has a reported budget of $14m.

Lee is weary of being asked about Ouroboros’s expense, but seems a bit put out – “Dammit!” she says good-naturedly – when the budget for Jones’s project is mentioned.

It may well be that, in a century or two, $14m will seem small change. Just like Ouroboros, Lee is an artist who dares to dream in eternity.

Matthew Westwood travelled to Brisbane as a guest of the National Gallery of Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout