Too much for the brain to take in

Are blockbuster exhibitions self-defeating?

HOW much art can you take? The question has come into sharp focus in Britain as long-simmering dissatisfaction with the blockbuster exhibition finally boiled over.

It's all very well, critics argue, to whip up a publicity storm with these cultural circuses, but are such spectacles about anything more than ticket sales income?

How many images can you look at before your feelings begin to founder, before your eye is exhausted, your brain overloaded and your emotions swamped?

A trip to the gallery is not like going to the cinema. There is no beginning or end. Having decided for yourself what is going to detain you, you are then required also to decide how long you must stay.

How long do you need? Besides the purely physiological and highly variable answer, which lies in the brain's limited ability to hold static images -- causing them after prolonged staring to appear to start jumping about, sliding all over the place -- the answer lies in that piece of proverbial string.

At one end of the argument is the art historian TJ Clark, who spent six months in front of two Poussin paintings. His record of the experience, The Sight of Death, offers a rapt account of what it means truly to look long and attentively and where such protracted processes of art appreciation can lead.

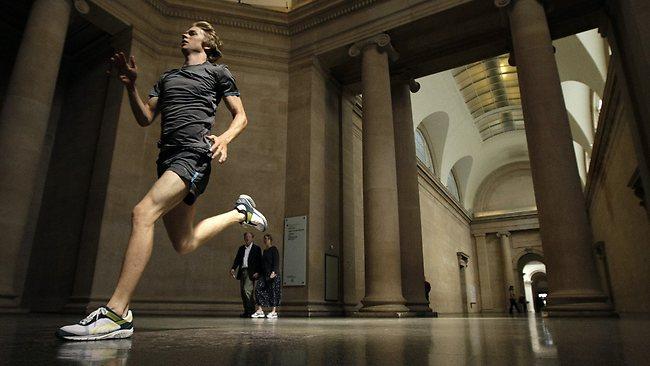

At the other end is the Turner Prize-winning Martin Creed. His Work No 850, in which a runner was released every 30 seconds to sprint through the spaces of the Tate, was dreamed up in response to his experiences on a trip to Palermo when, arriving at the catacombs five minutes before closing time, he found himself racing through trying to take it all in.

On the most basic level, different works of art will require different degrees of attention. You can run your eye over 20 Rothkos in the time that it takes to work out which story just one Rubens canvas illustrates. The assessment of a realistic figurative sculpture will feel far simpler than the visual gymnastics demanded by the wilful fragmentations of modernism.

In the past, art wasn't made for the museum context in which we now, probably for the most part, encounter it. It wasn't intended for the disinterested appraisal of the appreciator. Rather, for centuries, it was primarily religious, intended to convey Bible stories to the illiterate, to manifest divine mysteries to those who stood in slow contemplative perusal. Its meanings and messages were meant to settle slowly down into the emotional sediments of our spiritual life.

That doesn't mean artists haven't always competed to catch the spectator's eye: Michelangelo pitting the linear perfections of Florentine disegno against the bright Venetian colorito of Titian's canvases; the attention-grabbing Caravaggio painting his snapshot-style dramas; 18th and 19th-century Academicians vying to produce ever flashier and more spectacular effects.

But in the modern world, in which so often the looker is less the private patron with a lifetime to peruse their acquisition than a casual gallery-goer with a few minutes to spare, art more frequently strives for instantaneous effect.

Try passing a Bridget Riley without noticing. This explains the enormous success of the adman turned art collector Charles Saatchi. A tiger shark in a tank is the aesthetic equivalent of a vast wayside hoarding.

But just noticing is not enough. There is a world of difference between seeing and looking. "Ever since the 18th century people have been debating about what it requires to take in a work of art," says the psychoanalyst Darian Leader, who frequently writes on contemporary art. "They have been debating the oeillade: the look that can appropriate a work." But no consensus has ever been reached about how exactly the experience of looking at a picture can be explained.

Ten years ago, the National Gallery in London and the University of Derby conducted experiments involving an infrared camera which, by recording reflections and refractions, sought to monitor how humans absorb images.

A picture is not absorbed in a flash, apparently, but by a process of visual assembly. "The result of this rather mad experiment," says Alexander Sturgis, the curator of a show based on this research, was that "surprise, surprise, everyone looks differently".

Our idiosyncrasies put curators to the test. "We did some research at the National Gallery into what we called concentrated looking," says Sturgis, "and into how we could encourage people to engage in it. Just walking around a big museum is an exhausting enough process, let alone looking as well. But there is no answer. A single picture, hung in isolation with no writing around it and perfect lighting, might be what some people long for, but others will be completely put off."

"You might assume that going to an art gallery is about looking at art works," says Leader, "but it's just as much about looking at other people. When the Chapman brothers showed their McDonald's effigies many were shocked because the amazing thing about that show was that the room was dark and people could only look at the work, not at each other." Many shuffled away quickly to discuss it afterwards in the safety of their fellow group. This explains the mania that builds up around the blockbuster.

"In a sense we are not interested in art. We are interested in what other people are interested in.

"Built into how we see an art work is how someone else sees it," Leader says. As he explains in his Stealing the Mona Lisa: What Art Stops Us From Seeing, "visual images on their own might trap us, but for our capture to become more than transitory they need to take on a symbolic, signifying value".

"A place has to be made for them. Crucially, art works need to mean something for someone else."

Sturgis, as the director of Bath's Holburne Museum, a stuffed-to-bursting cabinet of curiosities, finds himself more than ever confronting the problem of how to persuade audiences to spend time with an individual work. "The rhythm of an exhibition is important," he says. "Spaces without work are as critical as the paintings. Gardens can be very helpful, like a theatre interval. And, for the same reasons, a cafe is great."

But if you ask someone to recall the most significant moment that they can remember experiencing in a museum, Sturgis says, it tends to be the moment they felt they had made a discovery. "Too many arrows pointing in the same direction saying this is the one to look at can be self-defeating." The thrill of hitting upon something all on your own is more powerful.

"If someone wants to discover my work they will," says Howard Hodgkin, whose abstract paintings are the product of months, if not years, if not a lifetime, of work, their surfaces until recently laid down layer by over-painted layer upon the canvas, nowadays laid down layer upon layer in his mind as he sits in contemplation. When the pictures are shown in a gallery, he can only hope for a fraction of this time back from the viewer.

But "it doesn't matter so much how long they look," Hodgkin says. "Some people can read a book very fast, others take ages. It is possible to get to the point quickly or to take a long time."

Although at first taken slightly aback, he was pleased when, in the course of his retrospective at New York's Metropolitan Museum, a young man approached him and said: "I wish you would stop driving my wife mad." He had found someone who couldn't stop turning his paintings over and over in her head.

In the end, the way we see art is profoundly personal. The famous art dealer Duveen understood this literally. He would habitually varnish his paintings, having noticed that his clients enjoyed seeing their own image in his works. Our relationship with art is far more than visual. It is social, emotional, philosophical and spiritual. You will push your way free of the thronged blockbuster when you have reached the end of your physical or mental strength. This could take three hours or three minutes. But there will probably be an image that you won't be able to push out of your mind. It will have outfaced you in the staring contest. It's not you who takes in the art, but the art that takes over you.

THE TIMES