The timeless temptation of infidelity

An adulterous relationship in middle age changes over time, but can love born of infidelity go the distance? Howard Jacobson gives it his best shot.

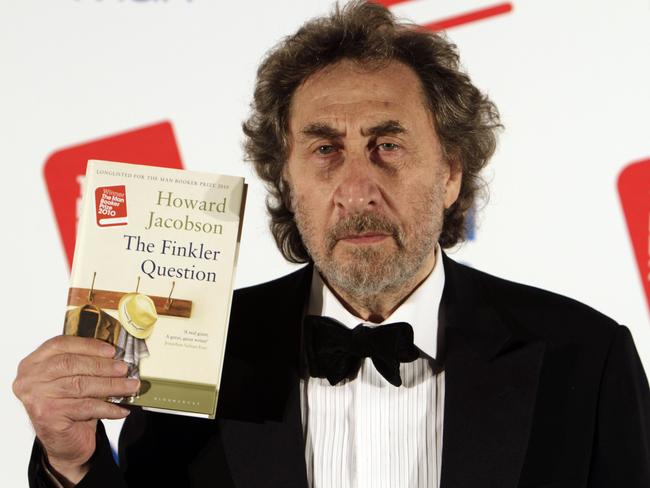

In his memoir Mother’s Boy, Howard Jacobson, who has been described as England’s answer to Philip Roth, describes how, at the age of 40, having not written anything of significance, he had an epiphany: he was a Jewish writer. In the 40 years since – he is now aged 81 – Jacobson has written 17 novels in which at least one of the main protagonists was Jewish, more often than not a Jewish man, an Englishman, often an academic (certainly true in his early novels) whose life is falling apart. This happens in the most hilarious way, his dissolution full of literary references and echoes, many of them from Shakespeare.

Mother’s Boy is an affecting memoir with a happy ending, something one might not have expected from reading Jacobson’s novels, none of which – except perhaps Live a Little, a love story of two elderly people – has what could be described as a happy ending.

Towards the end of Mother’s Boy, Jacobson writes of his marriage – to a Jewish woman – and of how this marriage, as well as the mentoring he treasured from the late Chief Rabbi of Britain, Jonathon Sacks, enriched his Jewish life.

Jacobson was always a fine newspaper columnist – his columns for the Independent newspaper, collected in Whatever It Is, I Don’t Like It, sparkle with wit and not a little wisdom. In recent years, Jacobson has been a fierce and prolific opponent of anti-Zionism and an often-scathing critic of that part of the left in Britain and elsewhere that characterises Israel as a racist settler-colonial state, a characterisation that quite often uses ancient anti-Semitic tropes.

In some ways, his Booker Prize-winning novel The Finkler Question, published in 2010, in which Sam Finkler, an anti-Zionist Jew, belongs to an organisation called ASHamed Jews (Jews who are proud to be ashamed of their Israel-supporting fellow Jews) was prophetic. Post October 7 there have been more than a few anti-Zionist Jews who have proclaimed themselves ashamed of Israel and the Jews who support it. And one can wonder whether in the current atmosphere, a book such as The Finkler Question could win a Booker Prize.

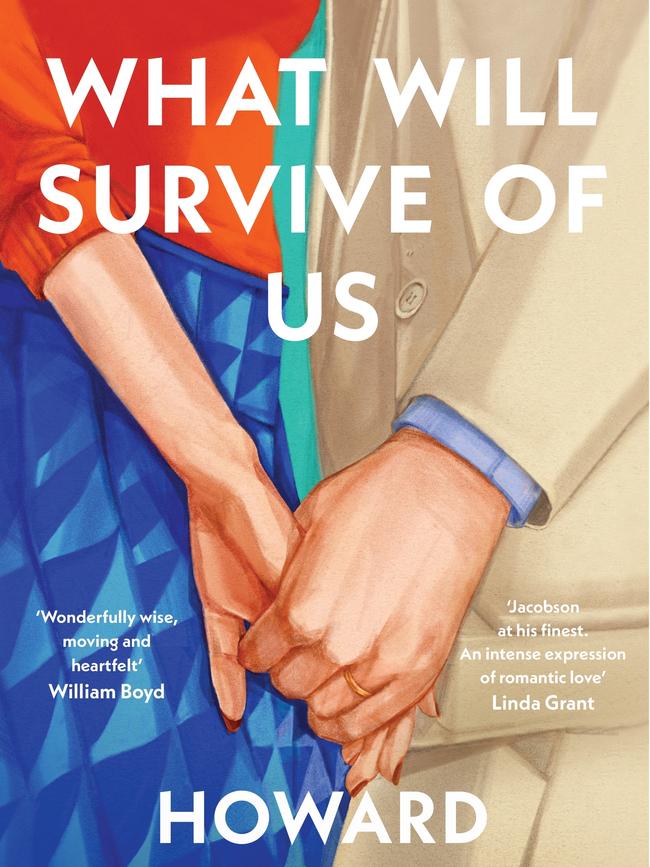

Which brings us to Jacobson’s latest novel, What Will Survive of Us. To be clear straight off: there are, as far as I can tell, no Jews in this novel (no ASHamed Jews; no half-ASHamed Jews; no Jews who think Israel is a central part of their identity as Jews; no Jews who feel that what is being increasingly asked of them, is to give up who they are, as well as who they have been all their lives.)

As a result, there is little of Jacobson’s Jewish voice in this novel by which I mean there is none of his unique English-Jewish humour which is not to say that the novel is humourless, not at all. At times it crackles along with a sort of sardonic, very English wit that is steeped in literary references, some of which I think I might have missed given there are so many.

This is a very English book. The title comes from the last line of the Philip Larkin poem, An Arundel Tomb, though Jacobson has left off the last word from the famous last line:

What will survive of us is love.

Which is intriguing because What Will Survive of Us is a love story that starts in middle age and moves rapidly – as time moves for most of us – into marriage and old age.

Sam Quaid is a playwright. Lily Redfern is a filmmaker – she makes documentaries about writers – and meets and falls in love with Quaid when she hires him to narrate the story of D.H Lawrence’s time in New Mexico. For Lily, it is, in Jacobson’s rendering, “Kerpow” at first sight.

Lily is in her late 40s. Sam is older but by how much is not clear. Both of them are married and for years, they conduct an adulterous relationship – it is much more than an affair – that, as they get older, changes and is reinvented and changes again. It includes a period of them playing sadomasochistic games and attending S&M clubs with an assortment of fetishes in London and Amsterdam and less likely places in the north of England. In some ways I found this the least convincing part of this fine book.

Sam and Lily are incredibly articulate. Their conversation, their verbal jousting, their talking of love and sorrow and betrayal and ageing, is full of wit and references and quotes from some of the greats of English literature.

These two are articulate in a way that in my experience, only a certain sort of English person articulates, people who were educated in Oxford or Cambridge and who carry within them, in their minds, like a reference library, the whole of the English literary canon.

Sam and Lily love each other in words.

Is there anything new to say about adulterous relationships one may ask? This is a big challenge even for a writer of Jacobson’s skill and verve. In the main, he meets the challenge. He is very good – and this is hard – at capturing the passing of time and with it, growing old.

Sam and Lily’s relationship changes over the decades in expected and unexpected ways. And their love for each other changes. Growing old changes what everything means, and has meant.

This is a book by a writer who has lost none of his wit and verve, who may himself be growing old, but who is still exploring the mysteries of love and whether it can last in some form, forever.

Michael Gawenda is the author, most recently, of My Life As A Jew (Scribe). He is a former editor of The Age, who lives in Melbourne, Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout