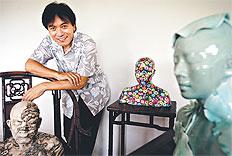

The Face: Ah Xian

AH Xian giggles into his green tea as he describes how he once recruited himself as a guinea pig and ended up in casualty with chemical burns.

AH Xian giggles into his green tea as he describes how he once recruited himself as a guinea pig and ended up in casualty with chemical burns.

It was the early 1990s. The Sydney-based Chinese sculptor was home alone when he decided to make a cast of his torso, using dishwashing liquid to insulate his skin from theplaster.

But as the cast began to set, the dishwashing liquid started to burn Ah Xian's chest. To his horror, the self-taught sculptor found he could barely move. "I couldn't even sit up," he says, now able to laugh at his painful predicament.

"You were cooked!" quips his wife, Mali, who had returned from a day out and resorted to knives and scissors -- "whatever I could find" -- to liberate her husband. Although Ah Xian's burns required hospital treatment, he insists that "luckily, they weren't too serious". Since then, he says dryly, "protection has been the first priority" when anyone poses for his casts.

Ah Xian's misadventure was part of a homespun experiment aimed at making decorated busts from casts of real bodies, a technique that eventually brought the sculptor life-changing success. "My whole living turned around overnight. It was very quick, sudden," he says in his slow, deliberate English. "I didn't expect it ... I never thought that one day I could live fully on my art."

Today, Ah Xian, who spent eight dispiriting years working as a house painter and five years fighting for asylum, can do just that. His luminous busts and full-body sculptures, created in partnership with artisans in China, command prices of up to $200,000.

They have been snapped up by the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, the Queensland Art Gallery, Sydney's Powerhouse Museum and the Art Gallery of South Australia. In 2002, a cross-section of his works was shown at New York's Asia Society Galleries, while a solo exhibition has been touring Germany and the Netherlands since 2007.

In 2001, he won the NGA's inaugural National Sculpture Prize for his life-sized sculpture, Human human -- lotus, rendered in cloisonne enamel. "To me, it was like winning Lotto," the artist says of snaffling the $50,000 prize for this work, which took three attempts and one year toperfect.

Drawn to traditional Chinese media such as porcelain and lacquer, he has recently turned to bronze. From next week, his series of 36 bronze busts, titled Metaphysica, will be on display at Brisbane's Gallery of Modern Art. This installation is part of a sprawling exhibition, Three Decades: The Contemporary Chinese Collection, which for the first time draws together the Queensland Art Gallery's extensive collection of modern Chinese art, the only one of its kind in the country. (GoMA is the QAG's second site.)

Three Decades will feature 50 artists and 146works encompassing sculpture, video, paintings and photography. These works were produced during the past 30 years, an extraordinarily fertile period for visual artists from the world's communist superpower.

Metaphysica comprises a colony of busts with bizarre objects on their heads: a bright red fish, a teapot, a pagoda. Ah Xian picked up these ornaments, believed to betoken good luck or health, at markets in China. "My idea is that people will believe in anything and when you put them all together, it seems senselesss or meaningless," he explains. He says he approached this work with a sense of playfulness; a lightness of spirit that was often absent from his early attempts to remake his life here.

From 1990 to 1998 he worked as a house painter in Sydney. The father of two could handle the physical demands of this work. "The difficulties were more on the mental side," he admits, confessing he has always had a melancholy streak. "I always wanted to do my own works. On the other hand, I had to work to earn a living to support my family. That was torture for me. Something that you love to do and desire to do, but no time, no ability, no money."

With extraordinary determination, he taught himself sculpture by reading books, in English, with the help of a dictionary. It was hard going. "Slowly, I learned," he says.

He also endured "five years of uncertainty" as his claim for asylum ground through various tribunals and bureaucracies. He had come to Australia as a visiting artist in 1990 and applied for asylum. Months before, in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre, prime minister Bob Hawke had allowed thousands of Chinese students living here temporarily to stay on. But Ah Xian's application for asylum was rejected: he was not a student.

Yet artists and writers in China had been targeted by anti-liberalisation police throughout the '80s. Ah Xian recalls spending a night in police custody in that decade for painting nudes, then considered a form of Western mind-pollution. "It was a warning," he says simply. Despite the risks, he kept painting nudes.

Finally, with the support of sinologist and writer Linda Jaivin and former cultural counsellor at the Australian embassy in Beijing, Nick Jose, he won the right to live in Australia in 1995. He is philosophical about that difficult time: "My belief is that whatever you've lived through, whatever you're faced with, is necessary. So what happened happened for a reason ... There is nothing to complain about."

Now 48, this shy, slight man, who rarely maintains eye contact, says being here has afforded him a decent living standard, peace of mind and sufficient distance from China to stimulate a renewed interest in Chinese culture.

Critics and collectors have been mesmerised by the strange beauty of his busts, which fuse a classical Western art form with Eastern decorative traditions. The sculptures' smooth skulls and closed eyes imbue them with a meditative, Buddha-like quality. Yet their tranquility is subtly disrupted by the traditional Chinese designs and motifs -- dragons, lily pads, trees, craggy mountains -- that snake around necks, cover mouths and eyes, glide over foreheads.

In Ah Xian's modest bungalow, perched high on a ridge in Sydney's southern suburbs, one bust has been exiled to a dusty corner and a baseball cap has been slung over its head. On a crowded mantlepiece is an exquisitely delicate sculpture of his daughter's hand, and on a stairwell sits a serene rendering of his wife's headand torso; Mali seems lost in her own interior world.

Ah Xian says he keeps such sculptures close by, in spite of their potential market value, because "I love them too much. It's a common expression, but they're just like my children."

Although he thinks of Australia as home, he splits his time between his homeland and adopted country; he makes the sculptures in China, and organises his work life from Sydney. His porcelain busts are painted under the artist's supervision by craftspeople from Jingdezhen, the traditional centre of China's porcelain trade.

When we meet, he is about to return to Beijing. As the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre approaches, it's a sensitive time to be going back. "The issue is still sensitive and the (Chinese) Government seems quite nervous and is trying to prevent people from commemorating the event," he says. Still, when asked whether there is more freedom of expression in China today than in 1989, he is emphatic: "For sure, a lot more. I would say the Chinese Government has changed a lot ... Now artists can do anything, even some things Western artists cannot do." Some artists in China, he observes, have used real corpses, including babies' corpses, in installations: a case, he says, of freedom of expression going too far.

Some critics have interpreted the Chinese designs on Ah Xian's busts as a comment on how one never escapes one's roots. For others, the busts illustrate the tension between East and West and reclaim Asian art forms often dismissed as craft.

Still others argue that with their closed eyes and mouths, Ah Xian's sculptures point to China's lack of democratic freedom. Ah Xian, however, plays down any political connotations, insisting his busts are primarily objects of beauty. Then again, he is happy for critics to draw their own conclusions. Sipping his tea, he says enigmatically: "Good art works are always very broad, wide open to interpretation."

Three Decades: The Contemporary Chinese Collection, Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, March 28-June 28.