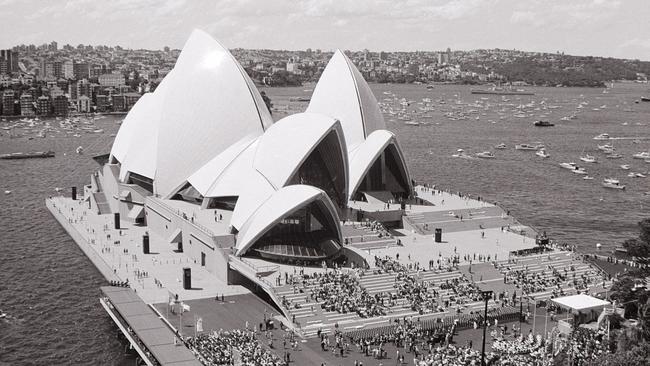

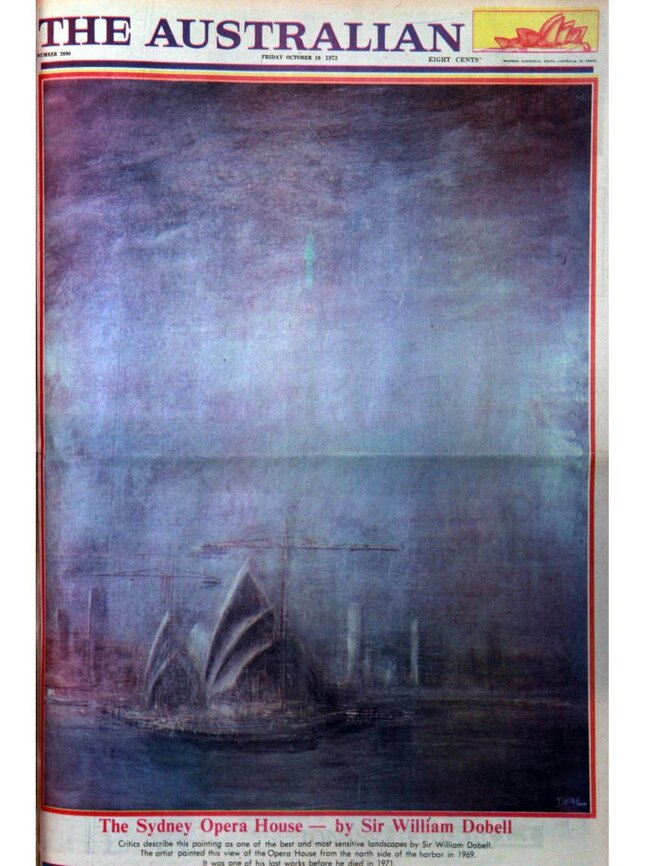

The day the Queen opened our ‘$100m shrine’

Massive crowds flocked to watch Queen Elizabeth open the Sydney Opera House in 1973, but there was one person missing: the building’s architect Joern Utzon. Or was his ghost a guest?

A MIRACLE: THEY GOT IT FINISHED

- By Stuart Gardiner. First published October 19, 1973

“Reflecting the mood of the sky by day, mirroring its glimmering lights on the water by night, the Sydney Opera House will perform its own exciting drama on the harbour.”

So said Joern Utzon, architect or seer, according to your point of view, in 1959. He added: “I am proud that my design was selected and am looking forward as much as you to seeing it take form.”

Fourteen years later, his wish has become a reality. And Utzon will be so conspicuous by his absence when the Queen opens the Opera House tomorrow that his spectre will surely drift above the curling sails.

It is difficult not to sound trite when describing the Opera House. It has been called the second Taj Mahal, equated with St Peter’s Basilica and the Palace of Versailles. Architects, engineers, writers, artists and poets have tried to capture its evocative sculpture.

It has been vilified and praised to the heavens; damned and exalted. Some worship it like a graven image. Primitive man would bow before it, and so would modern man if it wouldn’t crease his drip-dry trousers. People seem incapable of expressing their emotions about it except in terms of superlatives.

It has been a football for politicians to kick around; an election issue for 14 years; a great, gaunt, beautiful, incongruous, curvaceous, capricious mistress who has demanded too much of too many.

It has changed people’s lives. It has made men famous, Utzon for example, but other men too, like Ove Arup and Peter Hall.

Men have written books about it, yet the full story of 16 years construction and the expenditure of $100m will probably never be told. The professional jealousies and distrust, the human foibles, are hidden in the recesses of 1000 minds. Dinner-suited gentlemen will bow to each other tomorrow night with quiet decorum and a steely glint in their eyes will show they haven’t forgotten or forgiven.

Yes, there were arguments, crises, bitterness. But they got it finished, and in the end that is perhaps the biggest miracle and the greatest surprise of all.

Melbourne hates it, of course. The British are jealous of it. The Japanese cannot equal it, and both the British and the Japanese helped to build it. Brash Americans – who had a hand in it too – say they think it brash …

Sydney has paid $100m and bought a shrine.

WRITER WOULDN’T GET OUT OF BED FOR NOBEL ACCLAIM

- By Elizabeth Riddell. First published October 18, 1973

The Nobel prize-winner for Literature, 1973, has been cleaning the house all day and goes to bed at 9.30pm.

He is roused by a great banging on the door at 9.30pm and a demand for discourse.

Manoly Lascaris, who shares the house in a quiet street off Centennial Park, Sydney, went downstairs and staved off the invasion through a closed door while the dogs barked.

This is how Patrick White learns he has been awarded the prize. He has heard the usual rumours. There have been rumours every year since 1969, and even before. He learns to discount them. But now there is an official telegram. The Nobel prize committee does not alert its recipients, as is the case with honours from the monarch.

Some years earlier, White has the opportunity of refusing an honour from the Queen, as he has the opportunity of refusing an award of £5000 for the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

It is not in his mind to refuse the Nobel prize. He regards it as a legitimate reward for achievement.

People in search of an interview with White have to go to his house because he has an unlisted telephone number. He finds this convenient. He shares none of the urgency of some of his fellow writers about getting out there in front of the cameras and reporters and telling them all he feels about everything.

He is a shy, retiring and genuinely modest man and cares for publicity only if it will forward a cause such as stopping the Vietnam War, putting an end to censorship of the written word, or keeping a park for the people.

So he lets the press, TV and radio camp on his lawn and terrace and stays in bed.

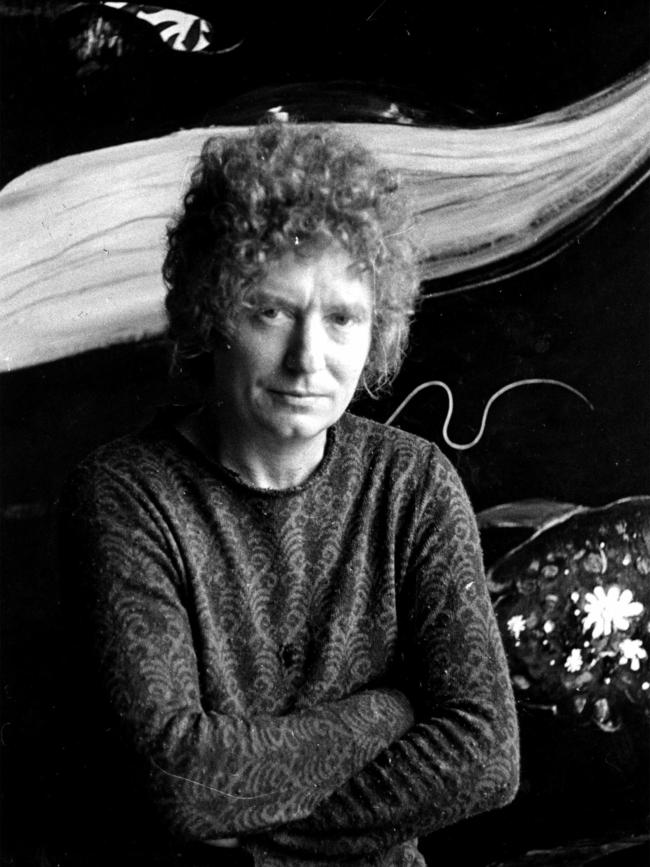

BRETT WHITELEY MAKES ART HISTORY - THEN GOES BUSH

- By Sandra McGrath. First published December 16, 1978

Having pulled off the art feat of the century on Friday, Brett Whiteley uttered a four-letter expletive and decided to go bush.

He had just become the first person to win the Archibald Award for portraiture ($3170), the Wynne Prize for landscape ($1000), and the Sulman Award ($1000) for genre painting.

It is the art hat-trick that will be remembered forever.

Whiteley’s Archibald entry titled, Art, Life and the other thing (self-portrait, Triptyche), is the most startling self-portrait ever done in this country. More than that, it extends the language of portraiture into new and exciting realms.

Whiteley gives the viewer three different self-images arranged into a medieval triptyche reference. On the right hand side of the central panel is a straightforward colour photograph of the artist’s face (Life?) set into a deep Perspex box.

The central panel shows a full length picture of the artist dressed in white overalls holding an ink pen. His face is painted in multiple images which is in contrast to the simplification of the background and the treatment of the body.

The pen is pointed toward a black and white drawing of Dobell’s Joshua Smith portrait – the disputed cause celebre of the 1944 Archibald. The historical footnote to the Joshua Smith sets up a series of references within references, which is provocative, as well as being typically Whiteley.

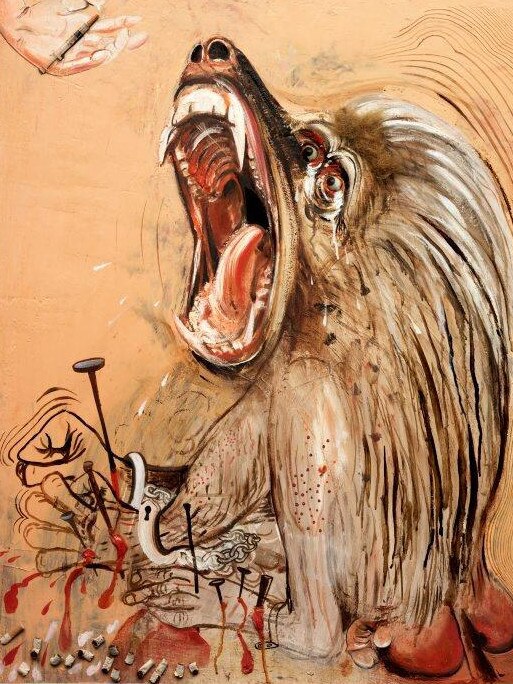

It is the third panel, however, to which the eye is drawn. In a powerful piece of drawing, Whiteley shows the image of a screaming baboon, his hands handcuffed amidst a scattering of cigarette butts, his arms pierced with nails, and bleeding. In the upper right-hand corner a hand holds out a hypodermic syringe. The message is blatant.

Whiteley on Friday night made the following comments on this self-portrait: “It is a very anti-dope statement.” (Referring to the baboon panel.)

“I wanted to try to describe the force of temptation or addiction. In many ways I painted the picture to make me quit having anything to do with dope. By painting the image, it was like dealing myself a card – something to look at that was so horrific that it would constantly remind me.

“For portraiture to survive, especially self-portraiture, there has to be a deepening quality of self-revelation. Portraiture shouldn’t be just paint on canvas. I see this self-portrait operating on many levels. First there is just a photographic image, then there is a subjective statement on art with the Joshua Smith references, and thirdly in the baboon image there is an attempt to paint a metaphor for an immensely strong force.

“How does one paint a powerful force, like jealousy, or rage? I guess the final message of the painting is trying to transcend all of this – the monkey being the most base – and trying to get out of the trap.

“In any case, the painting operates on personal levels. I have deliberately not made one pane Life or another Art or specifically designated ‘the other thing’. Some people may see the baboon as Life. You could say the monkey represented tortuous life, or that the monkey was art. The painting is trying to assault life on many levels, using three images.”

Of his other two wins there is also much to be said. Certainly the Wynne Award for landscape was richly deserved. Summer at Carcoar is one of Whiteley’s summarising works. It has everything. There is the familiar sweeping S curve of his beautiful river paintings, the delicious quality which we associate with his large works – in this case a burrowing field mouse, a patch of pansies, a crow, Italianate cypress trees – and the overall buttery yellows and wheat-coloured beiges which distinguish so much of his work.

The Sulman Prize which Whiteley won for a lyrical painting of a nude standing with her back to the viewer holding a mirror is also an environs picture.

Like the Archibald self-portrait, he has drawn into the composition the view from his house at Lavender Bay, a piece of his own property, a sculpture (his own), and a drawing.