The Australian film that changed cinema

This film’s purpose is original, daring and important: it is to ‘explain what Gallipoli means to Australia’s history and our understanding of ourselves’.

The Australian is turning 60 and we invite you to celebrate with us. Our first special series to mark the event is: Six Decades in Six Weeks, counting down to the 60th birthday of the masthead on July 15. Every day for the coming weeks we will bring you a selection of The Australian’s journalism of the past 60 years. Today we cover culture. See the full series here.

MASTERPIECE OF STORYTELLING THAT CHANGED AUSTRALIAN CINEMA

- By Evan Williams. First published August 8, 1981

So delighted was my first response to Peter Weir’s Gallipoli – though delight seems scarcely the word for a film so darkly suffused with this world’s pain – that even now, weeks after I had the privilege of seeing it, my inclination is still to doubt my judgment.

Was I unfairly influenced in its favour, or is it really the masterpiece it seems to be? It is true that one still feels a certain exaggeration and unnecessary loyalty to the local industry, a readiness to enthuse where modest praise is due. It’s true that I have a special admiration for Weir himself: and I suppose there was also – to put it no higher – a sense of simple relief that a film on which so many talents and reputations had been staked was not a self-evident disappointment. But, when all allowance is made for caution and partiality, one is driven to conclude that here, indeed, is a film of true nobility and greatness – as accomplished a work of art as our country has produced, a serene and poignant contemplation of our origin as a nation and the tragedy that shapes us.

Mr Weir is not simply concerned to make another powerful statement against war. Certainly, an abhorrence of war is implicit in the film’s conception, but the horror of its central events is barely touched on, let alone emphasised. Rarely has a war film been so discreet, even fastidious, in avoiding the details of bloodshed and carnage.

It is significant, I think, that the film does not deal with the first famous assault on Gallipoli – the tragedy we commemorate on Anzac Day itself – but with one of the several landings that came after. If Weir’s purpose had been merely to make a great battlefield epic – dwelling on death and spectacle and military incompetence – those first doomed assaults on the Turkish beaches would have been the film’s natural, and expected, theme. But, they are not. Weir’s purpose is more original, more daring and important: it is to explain what Gallipoli (and by that we mean the First World War) means to Australia’s history and our understanding of ourselves.

The film is an examination – to some extent a revelation – of enduring verities in our spirit and consciousness. It is a study, among other things, of idealism and folly, and the first serious attempt in an Australian film to come to grips with one of our formative traditions – the idea of mateship.

So far as it is possible for a work of entertainment to ask such question as “What is an Australian?” and “What has gone to make us as we are?”, Gallipoli provides some of the answers. The film’s abiding preoccupation is with waste and with loss – loss of face, the blighting and subversion of good and natural human instincts like courage and honour, above all, of course, the loss of life – specifically the destruction of a generation of the world’s manhood. I do not think the scale of this disaster – and especially the way it diminished and coarsened our own country’s history – will ever be fully grasped.

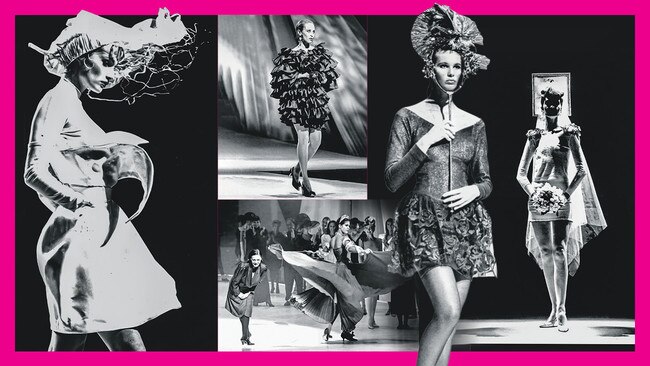

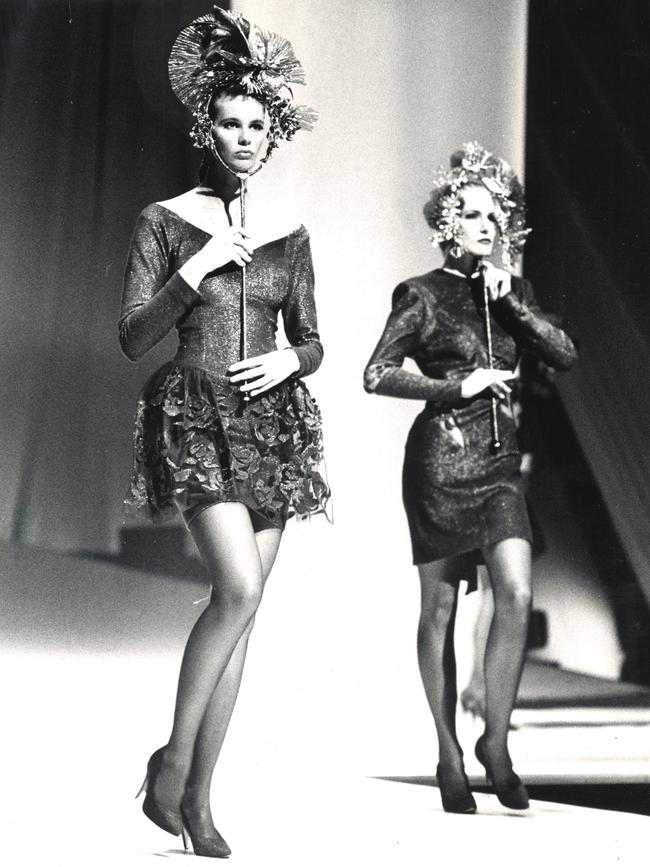

After an international fashion tribute to Australian wool, stafed for the Bicentennial celebrations at the Sydney Opera House, our columnist felt entitled to give his own critique

WOOL IS ALL OVER OUR EYES

- By Max Harris. First published February 13, 1988

Australia has given the muddled, seemingly rudderless fashion industry a new sense of function. It has been in a ritual rut and Australia has shown it the way to get out of it – by becoming a branch of the performance arts!

For a long time the fashion world has been floundering around trying to escape the tedious and outdated conventions of the walkway parade, and relying too heavily on the capacity of models to swivel and mince. For a decade they’ve tried to inject a bit of choreography, with a heavy reliance on disco jiggy-joggy.

In international television terms, Australia’s superb performance in applying the techniques and technology of performance theatre was the second occasion of its kind, but the first success. It will surely gall the French and the Americans.

Fashion as full-blood theatre first hit the headlines with the event inspired by Bob Geldof – Fashion Aid at the Royal Albert in London. It was a mess. The designers showed little sense of histrionic presentation: the lighting, score, timing and professionalism were scarcely Busby Berkeley.

The Opera House staging, mounting, timing, inter-cut clips and commentaries on the other hand were brilliant. The designers themselves gave thought to giving personal signature to their production numbers. Name designers are essentially exhibitionists who would like to run riot, but are limited by the fact that what they show is what they have to sell.

They have long lusted for audiences which don’t include a single buyer from Bloomingdales or Molton Brown. In Australia, they got what they dreamed of. That is, an escape from the limitations of the conventional genre in which they have to work.

The staging professionals in Australia also got it right. The entr’acte material was balletic in an old-fashioned way which provided diversions which ranged from Isadora Duncan at her most typical, corny examples of the tableau vivant which recalled Hermione Gingold and The Music Man, to some stylised choreography which I believe even Graeme Murphy would be proud to have claimed as his own.

The defects have been recorded, but I will be repetitious. It was embarrassing, and an amateurish indulgence of the cultural cringe, to engage poor old Parkie (Michael Parkinson) to talk through the event. It was a case of a cricket nut having an evening out bird-watching. And when his scripter (or was it an ad-lib?) had him dragging the Renoufs into his talky-talky, most adult Australians wanted to crawl under a living room cushion and hide.

The same feeling was aroused by the gasps and ecstasies, simulated for the plebs, about the Princess of Wales. Australia should be past royal rhapsodies. Here we have an honestly plain Sloane Ranger, with an over-long proboscis. We have a downcast coyness, induced by a need to get the couple of marbles in her head to rattle. We have a clotheshorse who exemplifies the sort of styles those with no sense of style choose to wear (as is the case with all the female royals). It would be a kindness to let her be. She is not doing anybody any harm (except designer Bruce Oldfield). The fainting TV commentators couldn’t even get her dress-length right. It was ankle-length, not calf-length.

The defect of a superbly mounted event was that Sydney can’t escape its parochial triviality, which it shares with Birdsville and Gang-Gang. Pity!

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout