Scenes from a marriage story: Hollywood’s war on love

From warring couples to family breakdown, the institution is taking a beating in film and TV.

Is it true that marriage is presented with a special sense of devastation in the recent film and television from our Covid-plagued world? It can certainly look like it.

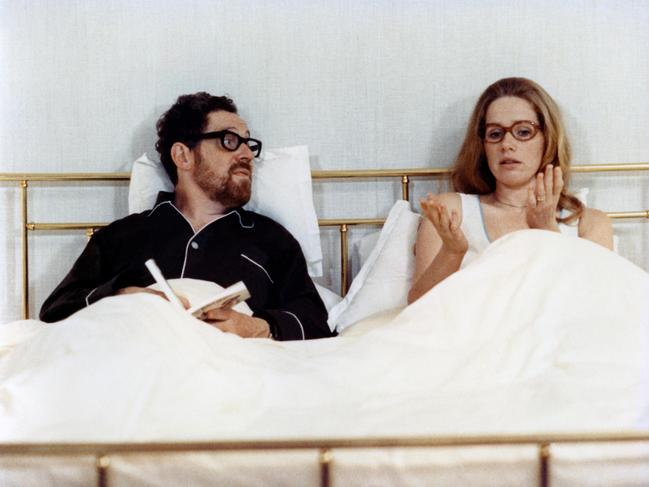

Bergman Island is about a couple who visit the island of the great Swedish director who depicted the storms and travails of matrimony, the heartbreak as well as the heartbeat of what brings people together and tears them apart. And Scenes From a Marriage, with Jessica Chastain and Oscar Isaac (screening on Binge and Foxtel Now), is an explicit remake of the extraordinary eight-hour epic – later cut to movie length – in which Liv Ullmann, one of Bergman’s long-time partners, and Erland Josephson, one of his principal actors, see what they can make of each other in a dark light when the marriage of true minds (in Shakespeare’s phrase) comes to admit all the impediments in the world and what seems to be love turns out not to be love, not any more.

Think of the newlyweds in the brilliant resort comedy The White Lotus – in which a young couple turn into a study of how poisonous a full-of-himself, spoiled young stud can be to a young woman who embraces marriage like a discipline she’s never learned the rules to. Connie Britton plays a masterful woman whose mousy husband (afflicted with a cancer scare) discovers that his beloved old dad was secretly gay.

Then there’s the marriage in the marvellous, deadly cold comedy, Physical, with Rose Byrne (on AppleTV+). Her husband is a would-be left-of-centre politician in Reaganite America and Byrne is left to perform all kinds of PR acrobatics while soliloquising about what a jerk he and all the potential rich donors are. Her one sensual release is secretly to roll around naked while devouring cheeseburgers by the score.

A fat fraction of the depiction of marriage on the streamers and cinema screens seems like the natural correlative of the plaguetime. In The Power of the Dog – even though the centre of Jane Campion’s film is Benedict Cumberbatch’s misanthropic cowboy – Kirsten Dunst plays a woman married to a plain and unromantic man, Jesse Plemons, and she turns to the bottle and can’t play the piano she used to love. The primary focus of the film (on Netflix) is on sexual repression in a man’s world, but marriage is presented as one of the distorting mirrors of doing otherwise.

And something comparable is true of Justin Kurzel’s Nitram (on Stan). The emphasis here – done with overwhelming power – is on the inner nightmare that leads to objective atrocity, with Caleb Landry Jones giving the performance of a lifetime. But the depiction of the marriage of his parents – played by Judy Davis and Anthony LaPaglia – is both bloodcurdling and extraordinary. He is all heartbreaking passivity while she uses her tongue on everybody like a razor: this is marriage and motherhood as scathing and terrible things.

Essie Davis is just as good, just as ghastly, as the woman who falls for Nitram and gives him not only the dream of Hollywood but endows him with all her worldly goods. If ever there was a parody marriage destined to end in massacre it is this doom-laden match, which begins with tinkled Gilbert and Sullivan.

A whole different piece of drama like Mare of Easttown (Binge, Foxtel Now) is a much more classical whodunit and is remarkable for the Dostoevskian depth it brings to characterisation. This is a world of marriages in dark entanglement, marriages that were or might have been, dead children, motherhood.

There’s also the light of deep attraction between Kate Winslet and Guy Pearce that suggests the optimism of a marriage to be. But this is very much a world of marriage and children; it encompasses brothers, it encompasses girl-on-girl romance (Australia’s Angourie Rice is brilliant as Winslet’s daughter) and Jean Smart is superb in her regret for the things done to the daughter by her mother.

Mare of Easttown is probably the most comprehensive image of life the streamers have given us, and while it is not a close-up of a single marriage it is forever shadowed and lightened by the marriages that have brought it into being.

Scenes From a Marriage is the other thing: the classic representation of marriage as destiny, tragedy and baleful entity that must be embraced or escaped even if the two aspects keep bumping into each other. Hagai Levi’s series (Binge and Foxtel Now) takes the great Bergman forebear as a precedent rather than ur-script to be followed through. You may remember the edits of the original Bergman version with Ullman and Josephson as well as the stage script that Australia’s Joanna Murray-Smith did for Trevor Nunn in London, and yet the Chastain-Isaac version is entirely its own piece.

Levi has brought to the story the same bareness, the same easy collapse into pits of intimacy and iniquity, the same wry sense, tragic beyond words, of two people who were made for each other, which is in turn a vision of the still blacker version of what they’ve made of each other. And in that sense it has the stupefying quality of Bergman’s original that makes you gasp in horror or in gratitude at having escaped the precipice.

Chastain is magnificent in her girlishness, in her imperiousness, in her ability to convey the temptation to endless seductive beguilement, and in her ultimate toughness and hardened sanity.

Isaac is every inch her match. It is the finest thing he has done: droll, urbane, long-breathed, constantly intent on a sanity that keeps slipping despite every move towards wisdom. It’s a wonderful, mature performance in a world where men are so often represented as boys.

Scenes from a Marriage is one of those occasions where America picks up the gauntlet of the grandest kind of European precedent and shows it can rise to it. Does this mean that Levi’s Scenes From a Marriage – and the complex wrestling with the great Swedish director’s ghost in Mia Hansen-Love’s Bergman Island, opening in cinemas on March 10 – only became possible because they coincided with the spectre of Covid?

Well, not quite. The streamers were already in place and in this precise area, think of Marriage Story, written and directed by Noah Baumbach, which we watched at the end of 2019 with Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver, when the idea of a pandemic was much more remote than the smell of bushfire smoke.

Marriage Story is not on par with Scenes From a Marriage but the original is one of its influences. Remember all that to-and-fro with the theatre company in New York? And then there was the brilliantly digressive structure with Laura Dern as the snaky lawyer who admires Scarlett, and Alan Alda as Adam Driver’s first lawyer who seems to be a bit of a clot. Eventually he comes to be represented by Ray Liotta, who is capable of the same sorts of forensic savagery as Dern.

There is a spectacular sense of legal conflict that gives Marriage Story a dramatic interest beyond the introspections and heartbreak of what the central couple go through, and there’s little doubt that Baumbach wanted the advantage that this extra dimension of dramatic amplitude would allow.

It is one of Driver’s better performances. The poignant scene where he confesses plangently to his hatred of Johansson is one of the finest things he’s done.

It’s also true that Johansson is at her most unmannered in Marriage Story. Something about the intimacy of the desolation represented here seems to have produced a performance much less cloak-trailing and much more closely observed. This is one of her best performances (in a more competitive field than Driver’s) and it’s fascinating that such an adult form of dramatic entertainment should have been sitting there just before Covid struck.

But that’s the point: Hollywood always knew there was more to drama than the kind of Oscar fodder that comes out of Sundance. So did Covid, with its manifest dangers of a heightened risk of mental illness and of people being locked up together lead to all this? Is this why Mia Wasikowska is in Bergman Island and Chastain is doing a Liv Ullmann in Scenes From a Marriage?

The answer is that Covid did not create but massively accommodated a heightened need for mainstream traditional drama and that’s somehow where we’re at.

Think of the great films about marriage and the enacted horror of marriage from the 1950s and ’60s. Think, in the first instance, of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in Mike Nichols’ film of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. There they were, the most famous husband-and-wife team of the day, tearing each other apart in the extraordinary drama of Martha – the loudmouthed hoyden who persecutes her mild professorial husband, George – and how the two of them play a “get the guest” game against a young couple, Sandy Dennis and George Segal. It has a lightning brilliance in the savagery and sparkle of its dialogue and it’s a monument to the way in which the intimacies of love sharpen the weapons of hatred. It has a tremendous power of articulation: a kind of “what oft was thought but ne’er so vile expressed” ghastliness.

What lies far in the back of Virginia Woolf? The fact that love is merely a madness? In political terms – very distantly – it’s the way in which contraception, the pill in particular, was separating marriage from the necessity and probability of having children. Taylor and Burton, who went through two impassioned and tumultuous marriages, never had a child together, which was no doubt a sorrow to both of them.

Think also of Marlon Brando in his “wifebeater” singlet screaming “Stella!” in the Elia Kazan film of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. Stanley and Stella are having a baby but the violence between Brando and Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois is extraordinary. Or think of Williams’ Suddenly Last Summer, and Sweet Bird of Youth. Nightmares like lobotomy, castration and cannibalism make the scenes from mere marriages look mild.

We’re back with streaming scenes from marriages and the particularity of families unhappy in their own way because we need more than bubblegum for teens, more than arty frolics for cineastes.

Marriage is the great dramatic subject: it always was and always will be.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout