Taylor who? Tasmania’s Mona Foma wows crowds in wild scenes

Queens of the Stone Age, Paul Kelly and Courtney Barnett kicked off the opening weekend of the Museum of Old and New Art’s annual summer arts festival. And, now in its 16th iteration, Brian Ritchie’s jovial jamboree was full a surprises.

Taylor Swift wasn’t there. No one was expecting her in Hobart, mind you. But, still, there was no Taylor. After all the acres of newsprint and reels and videos and TikToks and commentary dedicated to the first record-breaking Australian concerts in Melbourne by the world’s biggest pop star, it might be tempting to leave a review of any other cultural event at just that: Taylor was not there. The end.

But if the prevailing narrative last weekend was that it was only Melbourne having a good time, someone forgot to tell the Tasmanian capital.

At the opening night of Mona Foma, the Museum of Old and New Art’s long-running summer arts and music festival, the institution’s lawns positively were being trampled by a record crowd of its own.

The reason? A guitar-slinging American blond singer (calm down. Taylor wasn’t there, remember?): Josh Homme and his band Queens of the Stone Age.

At the same time 96,000 people were filling a sports stadium in Melbourne to see the tour-de-force Swift in action, a capacity crowd of 2500 no-less-dedicated music fans made the journey down the Derwent River to David Walsh’s sex and death museum to see QOTSA, the acclaimed five-piece desert rock group and the biggest drawcard of director Brian Ritchie’s three-week, two-city event.

The Californian rockers’ long-awaited return Australia, and to the Apple Isle, kicked off with their best-known song, No One Knows, an assault of distorted guitar and syncopated rhythm, before the band settled into hard-driving favourites including Smooth Sailing and the cheeky Make It Wit Chu.

Under a blanket of stars as one of Hobart’s hottest days of the past 12 months approached a steamy denouement, Homme took in the moment and gestured to the gleaming river.

“Look at where you live,” he exclaimed to a standing-room-only audience. “You lucky f..king bastards.” The band, which the previous night had performed a beautifully intimate semi-acoustic charity gig in MONA’s Nolan Gallery, finished its two-hour marathon set with crowd favourite Song for the Dead and a promise to return. “We will come here any time David Walsh asks us,” Homme exclaimed.

The MONA founder, who watched on from the balcony of his The Source restaurant, would do well to hold Homme to that.

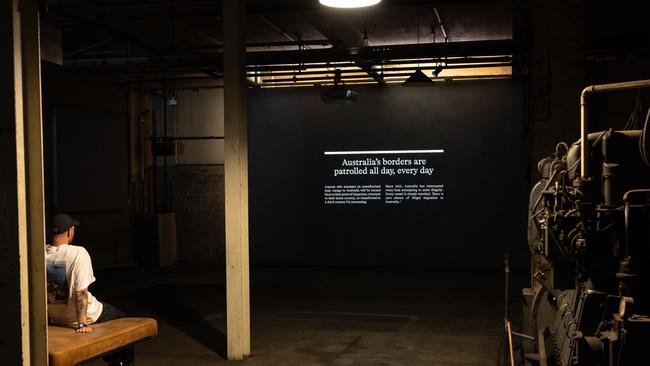

Back in the city at Penny Clive’s ever-engaging Detached gallery in the old Hobart Mercury building, Emeka Ogboh’s video work Boats was running on a continuous loop.

The Nigerian-born, Berlin-based artist’s immersive installation features montages of historical Australian newsprint on the theme of migration, from Federation, through Arthur Calwell and the White Australia policy, and on to the current political dialogue.

Pertinently, the room in which the work is displayed at Detached is the site of the original Mercury newspaper presses. The antiquated machinery sits heavily in the corner of the space, its cogs and parts thick with the redolence (if only perhaps for journalists of a certain vintage) of ink and grease, but also of a silent, uncompromising power.

Ogboh’s work is complemented by a gin collaboration with a local distiller and MONA chef, Vince Trim. The African-inspired alcohol is packaged in newsprint featuring mostly incendiary headlines about migration, interspersed with traditional Nigerian nsibidi symbols.

Ogboh says the work was inspired by former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott’s proclamation his government would turn back refugees who arrived on Australia’s shores under the notorious shibboleth “Stop the boats”.

Germanely, the day Ogboh’s work premiered in Hobart, a boat carrying asylum-seekers from Pakistan and Bangladesh arrived at Beagle Bay, near Broome in northern Western Australia; the following day, another group was located nearby.

“Anthony Albanese, Peter Dutton’s war of words after boat arrival”, screamed one news outlet’s headline. This writer returned to the gallery in the wake of the news. A fellow viewer stood in front of the video, its historic proclamations of White Australia and “boat people” piercing the darkness around her, and cried audibly.

At the nearby Odeon theatre, the overarching theme of the opening weekend – storytelling – was further revealing itself.

Darren Hanlon, that great, deep, foppish gent of Australian songwriting, started slowly but ultimately wowed the crowd with his collaborator, percussionist and composer Bree van Ryk, and the assured backing of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra. Halley’s Comet, 1986, was a sweet jaunt through the collective cosmic consciousness while van Ryk’s Light for the First Time, an orchestral composition for her daughter, was an emotional high point.

In the same space the following evening a younger generation’s (song)writerly hero, Courtney Barnett, held the audience in her grip.

The 36-year-old Melbourne singer-songwriter and multiple ARIA winner opened on a mesmerising instrumental with collaborator Stella Mozgawa, set to a film of Barnett bushwalking that unfurled behind the pair on stage.

The second half of Barnett’s set was dedicated to what the artist does best: playing guitar (sans band) and telling tales. Notable tunes were Depreston, simultaneously a paean to the notion of home and a funereal reflection on the housing crisis; and Breathing In, a true story about anaphylaxis and social anxiety.

On Sunday, a relatively small band of revellers – perhaps the only Hobartians not at the beach on an blazing 30C day – gathered at the MONA lawns to lay down their worries at the altar of acclaimed world music stars Ajak Kwai, Jarabi Band, Kgomotso Sekhu and Sui Zhen, repping their not-for-profit label Music in Exile in an eclectic display of rhythm, soul and meditative song.

This is Ritchie’s 16th Mona Foma. He remains the country’s longest serving festival chief. The event has matured significantly under his leadership, and in 2024 its position as one of the most dynamic programmers of especially music in the country is assured.

This coming weekend the festival hosts Scottish post-punk demigods Mogwai, while the festival’s March 2 shift to Launceston’s Cataract Gorge will be spearheaded by TISM (This Is Serious, Mum), that merry band of balaclava-clad intellectuals who so brilliantly terrorised the Australian music scene in the 1990s.

Broadly, the 2024 program has a less radical bent than in previous years. There were two outliers, however, at the weekend in Arka Kinari, a kaleidoscopic cinema and live music spectacle, ostensibly about climate change, set on a 70-tonne sailing ship at Franklin Wharf, and Justin Shoulder’s solo performance at the Theatre Royal titled Anito, an exploration of the so-called Skyworld, “a Queer Filipinx Future Folkloric space of storytelling”.

By any measure, though, Mona Foma remains that surest of things. It’s occasionally weird, invariably surprising, and at its heart remain two solid foundations – the magnetic power of MONA and inspired music programming, the latter connected in no small way to Ritchie’s day job as the bass player for globally renowned rock band Violent Femmes.

With respect to the former, a constant stream of visitors made their way through the institution’s two excellent major visual arts exhibitions: the religious Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World; and Hrafntinna (Obsidian), an immersive sound and light installation by Sigur Ros musician Jonsi inspired by the 2021 eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano in his Icelandic homeland.

As MONA’s winter sister festival Dark Mofo takes its curious hiatus this year – a minute’s silence please, for oldly minted Dark director Chris Twite, whose maiden event was put on ice before it even began – might Mona Foma also be looking for ways to shake things up, as may be the wont of a festival and a funder-museum largely, but not entirely, free of the strictures of the public purse? Time will tell.

What was clear was the Hobart sky, and as the weather cooled on Sunday evening and the weekend drew to a close, there was only one man to take us into that good night. Paul Kelly, the godfather of gravy, took the stage at the Odeon with his band, including nephew Dan Kelly and singer Jess Hitchcock, and performed to a sold-out house.

In a 90-minute set, Kelly performed songs from his compilation album Time, including a tender rendition of From Little Things Big Things Grow, about the Wave Hill Walkoff, and the lilting and beautiful Time and Tide, written with the singer’s Kimberley kin Alan Pigram. Hitchcock’s vocals were an agreeable and powerful complement to the troubadour’s musicianship and storytelling nous.

Kelly raised the roof with ravishing versions of Deeper Water and How to Make Gravy before gracing the stage for a rapturous encore in Leaps and Bounds. There might have been a metaphor in that title for Ritchie and his festival, which has indeed come a long way since 2009, but so too was there a subconscious nod to She Who Was Not There. Sang Kelly:

I’m high on the hill

Looking over the bridge

To the MCG …

That’s where she was, of course. The phenomenon that is Taylor Swift was at the G, playing her third critically acclaimed mega-show in three days to those Melburnians blessed with ticketed good fortune.

And while the world was looking over, Australia’s greatest singer-songwriter was standing in a full house in Hobart, smile as wide as the Derwent Bridge and guitar (a Taylor, incidentally) slung over his shoulder, telling the stories of this place, in a place that understood.

Tim Douglas travelled to Hobart with the assistance of Mona Foma.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout