Writer polishes a goldfields gem for a modern audience

Australia’s first Chinese novel, from 1909 and long forgotten, gets a new life onstage - first in Brisbane in May and then at the Sydney Theatre Company in June.

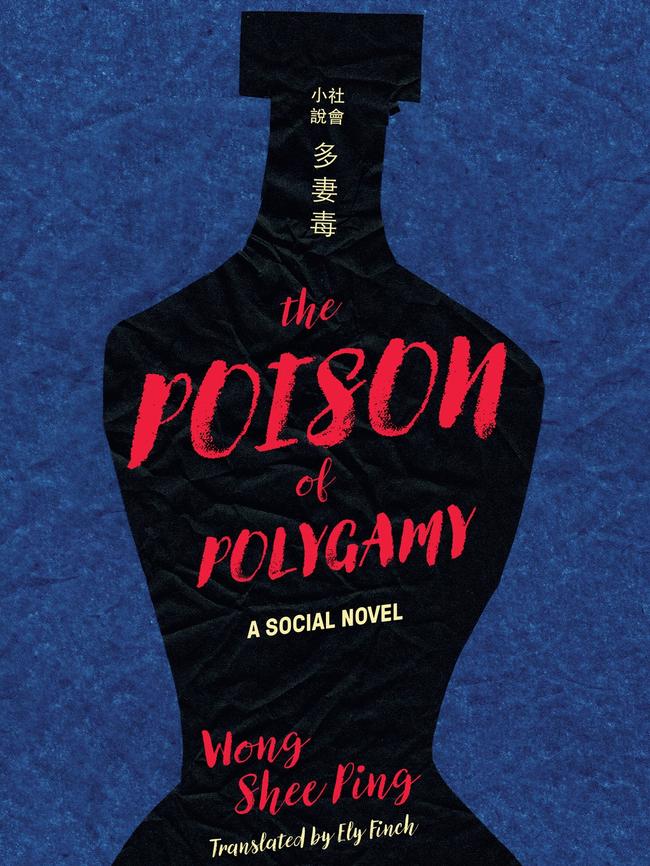

An astonishing story of Australian publishing began in 1909 when a Chinese-language newspaper in Melbourne, The Chinese Times, started running episodes of a serial novella called The Poison of Polygamy. It is the first known novel by a Chinese author in Australia – but until recently the writer’s identity was a mystery.

The Poison of Polygamy is a picaresque tale of life on the Victorian goldfields. Sleep-sick, a young man from Guangdong in southern China, leaves his home as he goes to seek his fortune in Australia. He has solemnly promised his wife, Ma, that he will be faithful but when he arrives in Victoria he falls for the seductive wiles of Tsiu Hei. It is described as a social novel, in which the narrator editorialises about the sin of marital faithlessness.

The story, which The Chinese Times published in 1909-10, is now being brought to the stage. Anchuli Felicia King, a writer of Thai descent who works in theatre and TV, has done the adaptation. It will have its premiere at La Boite in Brisbane in May and then transfer to Sydney Theatre Company in June.

“It’s a rollicking story, a deliciously dark, almost Dickensian novel with drugs and an odyssey into Australia’s goldfields, and an evil concubine,” King says. “It’s a great novel, and a remarkable piece of our cultural heritage that has languished in obscurity for a century and I think it deserves a wider audience. It’s a celebratory act to theatricalise it and bring more attention to it.”

King says The Poison of Polygamy is a kind of social parable, with the writer trying to convince the reader that contemporary Western, Christian values are better than the old Chinese ones.

“That’s a recurring theme throughout the novel, critiquing what were viewed as backward practices in China at this crucial juncture in Chinese history,” she says. “It’s a snapshot of early globalisation, really, and the imposition of a Western Christian morality on Qing dynasty China. What I find interesting as a contemporary reader is that we are still having the debate about polygamy, polyamory and monogamy, but in a very different social context.”

King was the Patrick White fellow at Sydney Theatre Company and looking for ideas for new plays when she came across an English translation of The Poison of Polygamy. The serialised novel was rediscovered in 2018 by historian Mei-fen Kuo; by the next year, translator Ely Finch had made an English-language version. King has been active in bringing Asian stories to the Australian stage in her plays, including White Pearl and Golden Shield.

When she read an article about The Poison of Polygamy, she knew she’d found a potential subject for a play. STC commissioned her to write the play and brought Courtney Stewart, a former associate director at STC, now artistic director at La Boite in Brisbane, on board as director. Rehearsals start next week.

The original story was published anonymously, but detective work led to the discovery that the editor of The Chinese Times, Wong Shee Ping, was also the story’s author.

Wong’s personal story is no less astonishing than that of his fictional creation. Born in Guangdong in about 1875, he was a member of the Kuomintang Chinese nationalist party and a minister in the Church of Christ. He had followed his father to the Ballarat goldfields when he was a young man and used his rhetorical skills for sermonising and rallying others to the cause of Chinese republicanism. King says Wong’s world view is evident in the pages of The Poison of Polygamy.

“He is deeply critical of what he views as a barbaric, polytheistic, Taoist China at the time, and everything in the novel is framed through that lens,” she says. “It’s meant to be a kind of social parable. There are all of these italicised passages where he ostensibly preaches his world view. In line with his politics, he was espousing Western Christian values to his Chinese readers. The novel is called The Poison of Polygamy because he is highly critical of what he views as this outdated practice of polygamy, which he regarded to be a sin.”

In adapting the adventures of Sleep-sick for the stage, King has invented the character of the Preacher as a narrator and framing device for the action to follow. The Preacher is not a stand-in for Wong, King says, but he allows her to give expression to some of Wong’s opinions.

“The challenge of adapting the novel is that I’m not speaking to the same audience that Wong Shee Ping is speaking to,” King says.

“Part of the framing device of my adaptation is a preacher-narrator who is speaking to us from his eternal purgatory, and that allows me to be in conversation with the politics and the social world-view of the novel, and sometimes to problematise it.

“One of the things I am interested in is the thorny history of Chinese-Australians as settlers, and the corruption and exploitation of the land for greed, and where Chinese-Australians fit into that narrative, which is a pretty uncomfortable piece of history. This novel is so much about the goldfields experience, and I felt compelled to feed more of the history into my adaptation.”

The story was published during the dying days of the Qing dynasty in China and the early years of Australian Federation. King has weaved into her adaptation contemporary historical references, including the racism experienced by Chinese migrants that was formalised in the White Australia Policy.

“I felt compelled to weave some of that history into my adaptation more than it is present in the novel,” King says. “Wong Shee Ping is very much speaking to his contemporaries, who were aware of the treatment they were experiencing. And in some ways, in the novel, he glamorises the Europeans and how the Chinese go along with them. But, of course, Chinese settlers faced enormous systemic violent racism, and it was enshrined in law. A lot of the history of that period, including the Boxer Rebellion and the legislation that was passed against Chinese migrants, I have tried to weave into my adaptation.”

Stewart has chosen the play to open her inaugural season as artistic director at La Boite. She is a fourth-generation Chinese-Australian and, like King, is keen to bring stories to the stage that represent modern Australia.

“I love the fact that it’s the first novel to depict the Chinese-Australian experience,” she says.

“Chinese people have been in this country for a really long time, so I was interested in looking at how we tell the story of the Chinese diaspora of then, told by the Chinese diaspora of now.

“It’s so exciting when you have a brand-new Australian work that’s epic, that’s ambitious, that’s a saga, that travels across time, space and geography. I love it when writers take agency over having big ambition. I’m very passionate about expanding the Australian canon and we need works of scale to do that.”

Stewart is staging the play in the round and with a cast of eight. Some of the actors double their roles so that, for example, Shan-Ree Tan appears as Sleep-sick and as the Preacher. The cast also features Merlynn Tong as Ma and Kimie Tsukakoshi as Tsiu Hei.

“Our entire cast are incredibly virtuosic and are able to switch and change between the different characters seamlessly, to deliver a great ride for the audience,” Stewart says.

“(The play is) very episodic in nature, which is to be expected because the novel was serialised and published chapter by chapter in a newspaper, and Anchuli has kept that episodic feel to the work. So it moves very quickly, it’s quite pacey. We have decided to present it in the round, which opens up a lot more opportunity to lean into the theatre-making of it.”

King lives her life out of a suitcase, travelling between Los Angeles, New York, London and Australia and working on various projects including TV shows for HBO in the US, AMC in the UK and Amazon Prime in Australia.

She is currently in a writers’ room in New York with the makers of a new TV series, Billion Dollar Whale, whose producers include Beau Willimon (House of Cards) and King’s mentor, Tony award-winner David Henry Hwang. The story is based on a book about fugitive Malaysian financier Jho Low.

Asked whether she prefers working in live theatre or for the screen, King says she finds both are rewarding in different ways.

“In TV, we are sitting together for 10 or 20 weeks, a group of writers, and we all come up with a story together, and then we go away and write. Whereas in the theatre, you are writing on your own, and then you get to bring it to life with a bunch of other people. The lonely part of the process is inverted. But at the end of the day, both are still super-collaborative.”

As she prepares for the premiere of The Poison of Polygamy, King can claim another kind of attraction of the heart. “I think I’m artistically polygamous,” she says.

The Poison of Polygamy is at La Boite Theatre, Brisbane, May 8-27, and Wharf 1 Theatre, Sydney, June 8-July 15.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout