Megan Phelps-Roper on defection, family rejection and making the riskiest podcast of our time

Megan Phelps-Roper still deals with the fallout from leaving a sect dubbed America’s ‘most hated’ family. That hasn’t stopped her from tackling our era’s most divisive social issue.

Megan Phelps-Roper was visiting New York when she learned on Twitter that her mother, sister and aunts were planning to stage a religious protest just a couple of blocks from where she was staying. It was 2016, and Phelps-Roper had not spoken to her family since she left the Westboro Baptist Church – founded by her grandfather Fred Phelps and often condemned as a hate group – four years previously.

When she left the church – which routinely vilifies gay people, Jews and Muslims, and has prayed for the deaths of American soldiers – Phelps-Roper, then aged 26, knew her closest relatives would cut her off. Over Zoom, the church spruiker turned critic tells Review in a small yet unwavering voice: “The assumption is you will never speak to them again. If you see each other in public, they pretend they don’t see you at all. It’s an incredibly painful and horrible situation.”

Nonetheless, several years after her 2012 defection, the then 30-year-old felt an overwhelming urge to share some pleasing personal news with her mother: “I had wanted to tell my mum that I was engaged for several months. I didn’t want to do it in a letter.” So she turned up at the Westboro protest in Manhattan and attempted to tell her mother about this happy turn of events.

It did not go well.

She recalls: “My mum looked completely shocked to see me there and two of my aunts started yelling at the top of their lungs – another horrifying situation. I did get to say to my mum what I wanted to say and it was very painful.”

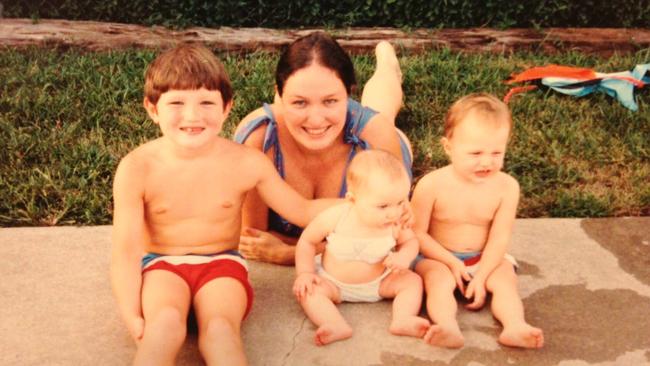

One of 11 siblings, Phelps-Roper was born into the sect and grew up in an insular church compound in Topeka, Kansas. Her childhood was a disorienting blend of the ordinary (attending local schools and reading the Harry Potter series) and the grotesque. She has written that “from the age of five, I protested with my parents, siblings and extended family on sidewalks across America – including outside the funerals of AIDS victims and American soldiers”.

This Christian cult – which has been the subject of three fly-on-the-wall documentaries by Louis Theroux – believes such deaths are God’s punishment for America’s acceptance of homosexuality and other sins.

Today, Phelps-Roper is 38 and a critically acclaimed author and podcaster who will be a headline speaker at Sydney’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas next month.

A law graduate, she is thoughtful, articulate and shy, often shifting her gaze sideways while speaking from the South Dakota home she shares with her lawyer husband Chad Fjelland and their two young children. Her dark curls cascade down her right shoulder, and she laughs knowingly as a neighbour looms into view on Zoom in her picture window, pushing a mower around his large green lawn.

She is a poised and polished speaker – her 2017 TED talk on being raised in and leaving Westboro has had 6.5 million views – yet at times you can glimpse the anguish behind her extraordinary self-possession. “It’s ongoing, I guess, is what I’m trying to say,” she says of the emotional fallout from her decision to quit the church with her sister Grace. “It might be easy to think: ‘Oh, it’s been 11 years, almost 12 years’, but it doesn’t go away, that desire. I love my family. I very much hope that one day they will be able to see (that).

“I still send them letters and gifts and not just messages of love, but also specific messages, trying to help them recognise the places where Westboro doctrines are hypocritical and unbiblical.”

Since venturing into the real world, the 21st-century prodigal daughter has worked on everything from school anti-bullying campaigns to legal agencies’ deradicalisation programs. This woman who once thought it a rare treat to go shopping without permission has given an address at Oxford University and in 2019 published a memoir of her life inside and beyond the church, Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope. The New York Times described Unfollow as “a nuanced portrait of the lure and pain of zealotry” while The Sunday Times said it was “a gripping story, beautifully told”.

Last year Phelps-Roper and her podcasting colleague Andy Mills scored an international scoop: Harry Potter author JK Rowling agreed to give them her first extended sit-down interview on her contentious views on gender and sex, and this evolved into the seven-episode podcast The Witch Trials of JK Rowling.

Initially, while researching The Witch Trials, Phelps-Roper felt the chances of Rowling agreeing to an interview were “incredibly remote”. When the Harry Potter author and outspoken feminist agreed to speak to her, “it was utter shock”. There was an element of serendipity about this: Rowling had received a signed copy of Phelps-Roper’s memoir as a Christmas gift in 2019.

At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Phelps-Roper will tackle the topic The Witch Trials: The Revelations and Unanswered Questions. As she notes in an essay accompanying the podcast, Rowling’s views – first expressed in a 2020 tweet mocking the phrase “people who menstruate” and in a subsequent essay – turned her, in the eyes of detractors, from a progressive saint into “a kind of Voldemort – the villain of villains of her own stories”.

Phelps-Roper writes: “TikTokers started a trend of covering her name on books and book jackets, and tore her books apart … The abhorrence of Rowling has at times been so intense that it’s led to the actual burning of her books. A recent novel even includes a scene where Rowling herself is killed in a fire … The head of the biggest Potter fan site in the world said she was ‘heartbroken’ and shared a guide on ‘cancelling’ Rowling, while others accused the author of ‘destroying her legacy’.”

In clear, crisp tones the Harry Potter author says in the podcast that writers who cared about fame or their legacy more than she does would have been mentally destroyed by the kind of abuse she has received.

It’s tempting to see parallels between Westboro’s persecution of Phelps-Roper after she defected and the attacks on Rowling from pro-trans activists and – in an earlier wave of attacks – from fundamentalist churches. As the podcast reports, some evangelical American churches believed Rowling’s wildly popular books made witchcraft appealing to children and were poisoning their minds. In the 1990s and early 2000s, some burned her novels and tried unsuccessfully, to have them banned from schools.

Phelps-Roper says that in the months after she left Westboro, church members doubled down on their use of homophobic signs. She had objected to these offensive signs, which declared “gay people can’t repent” and “gays are worthy of death”. Once she defected, these slogans “were suddenly everywhere. My cousin changed her profile picture on Twitter to be her holding those two signs screaming into the camera”.

For the next 18 months Phelps-Roper gave interviews and wrote letters to her family arguing their posters were “clearly unbiblical”. Finally, they produced a blog post that disavowed the signs. This was a small step but one “that was incredible to me because it was proof that they could be persuaded against their will, basically, that they could be wrong”, she says. Before this, she says, “we had these horrible, horrible signs saying things like ‘pray for more dead soldiers’ – those are no longer used. I know it is an incredibly low bar to say that they stopped praying for people to die, but you know, you’ve got to start somewhere.” She chuckles self-deprecatingly; evidence, perhaps, of the black humour she has relied on to survive a life of indoctrination and repudiation by those she was once closest to.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas describes the Witch Trials podcast as “divisive” and “one of the most thought-provoking podcast series of our time’’. Phelps-Roper was working as a researcher on it when Mills – a co-founder of The New York Times’s podcast The Daily who was also involved in the newspaper’s discredited 2018 podcast Caliphate – asked her to host it.

She admits she hesitated before accepting the offer: “Obviously you can’t look at this conversation around sex and gender over the last years and not see that so many people’s lives have been completely up-ended by choosing to engage, even in the smallest ways.’’

Then she remembered her first appearance at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas in Sydney in 2018, just three weeks after giving birth to her first baby, “and talking about the importance of good faith conversation; acknowledging that yes, it can be dangerous … but in a pluralistic society it is essential to find a way forward out of very difficult conflicts.” When she recalled that speech, “I felt like a coward that I hesitated at all.”

Despite its title, she says The Witch Trials of JK Rowling examines the contest between transgender and women’s rights from “all sides”. In this incendiary debate, she discovered that “people on all sides of the conflict saw themselves as victims of a witch-hunt”.

She adds carefully: “I do not believe that Rowling or anybody should be above criticism … I would never say, ever, that all the criticism against her has been unfair. But of course there are also extreme examples – things like death threats (against the author).” Moreover, while the podcast depicts attempts by pro-trans activists to shut down meetings by gender critical feminists, she is unaware of any attempts by feminists to suppress trans protests.

She and Mills have worked on a new podcast show called Reflector, which last month released two episodes, You Can’t Say That, Part One and Part Two, offering updates on the gender debate and interviews with Rowling’s transgender critics, some of whom apparently feel the original podcast was too sympathetic to the bestselling writer.

Phelps-Roper’s introductory essay to The Witch Trials asks a question many of us have wondered: Why has Rowling chosen to die on this hill? She says the answer lies in the Harry Potter author being a survivor of serious sexual assault and past domestic abuse and her upbringing as a feminist. “Then there’s the broader question of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly. She defends those liberties, even for people she vehemently disagrees with.”

One of the most polarising aspects of this debate is gender affirmation treatments – hormones, surgeries and puberty blockers – for minors. Trans activists say they are lifesaving, while countries including Britain, Finland and Sweden are taking a more conservative approach because of concerns the evidence base for such treatments is low.

In the podcast, Rowling says: “We are dealing with children, in my view, being persuaded that a solution for all distress is lifelong medicalisation. That is real-world harm … I genuinely think that we are watching one of the worst medical scandals in a century.”

Phelps-Roper adds: “It’s definitely not just JK Rowling’s view that the evidence view is very small. It’s something that’s widely acknowledged.” She says Britain’s highly influential Cass report also reached this conclusion while stopping short of supporting blanket bans on treating childhood gender dysphoria.

“The emerging consensus seems to be that more research and more caution is needed,” she says. Phelps-Roper says the podcast’s aim was to bridge an ideological divide and that she and her colleagues did “everything we could to help people understand one another in a conversation where emotions and fears on all sides have run very hot for a long time. I’m incredibly proud of what we made.”

L ouis Theroux called his 2007 BBC documentary about the Westboro Baptist Church The Most Hated Family in America. Given that the church then had a few dozen followers, most of them Fred Phelps’s relatives, this was clearly hyperbole.

Nonetheless, Theroux’s marketing strategy worked – the documentary was broadcast around the world and spawned two sequels. In the first sequel, Return of America’s Most Hated Family, Shirley Phelps, Megan’s mother, opens the door to the amiable host while wearing a red T-shirt that says: “Jews killed Jesus.”

Shirley flips through a collection of “cute” anti-gay and anti-Semitic protest placards made for small children – “mini-signs made for mini-hands” she calls them, her tone and manner as bright and chirpy as if she was rifling through a recipes drawer. She calls Barack Obama “the anti-Christ” and adds that when “rebels” – presumably including her daughters Megan and Grace – left the church, she felt “unburdened”. In contrast, in a subsequent 2019 interview with Theroux, she weeps over the fact several of her children have defected from Westboro.

One might assume that having your relatives labelled the US’s “most hated family” would upset the church’s members. However, Phelps-Roper, who has toured Australia with Theroux, says her family “absolutely loved that”. She was a 20-year-old university student when the British filmmaker came to her family compound to make his first documentary about them. “We didn’t care if he would mock us, we just wanted to essentially use his platform to publish our message,” she says.

As children, they were taught to focus on New Testament phrases about Jesus and Christians being persecuted and reviled. Her grandfather told her “we should wear it as a badge of honour, that we were hated”.

Counter-intuitive as it seems, she came to reject the church’s poisonous doctrines through Twitter, a platform best known for its vicious pile-ons and reductive rhetoric. (She also met her husband through these Twitter debates.) Because she grew up on a compound, “so much of the engagement that I had with outsiders was happening on the picket line. This was a place where there was a lot of yelling, sometimes physical attacks.” By engaging with Westboro’s critics over time on Twitter she started to see them “as human beings who are really trying to do the right thing”.

She also debated with people who tried to understand Westboro’s “dense theology” and pointed out contradictions in the sect’s beliefs. “The question that comes up quite quickly on the heels of that realisation is, ‘What else are we wrong about?’ ”

Her life on the other side of the compound was documented in Theroux’s third Westboro documentary, Surviving America’s Most Hated Family. Theroux was criticised for including a scene in which she breaks down when told her sisters are engaged, but she defended him, arguing that “he’s showing my family – who have cut me out of their lives … my candid reaction to this news”.

Interestingly, unlike other fundamentalist churches, Westboro had no issue with Rowling’s books. Phelps-Roper says “my dad, who was one of the church elders, brought home the first book (Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone). He read it and loved it.” He gave it to her and “we all were very avid readers of those books, avid readers generally, and we loved them. I remember telling Jo (Rowling) about standing on the picket line, balancing this huge book on my picket sign.”

She notes that her eldest child is now five, “the age now that I was when I started protesting, which is wild”. Looking back at who she was 11 or 12 years ago, is she shocked at how she has changed? “Absolutely,” she replies. “I could not have imagined any part of this. For years, I would get excited to go to the grocery store without permission.”

She is also amazed by “the fact I am married to a wonderful man and that I have these two incredible children; that I believe the things I believe; that I am able to love people now in a way that can be recognised as loving and not this sort of twisted version that I lived at Westboro for all those years”.

As for dangerous ideas, she says nuanced debate about difficult topics is under threat in our society. “It’s part of why we wanted to make the (podcast) series. It’s under threat in a number of ways; it’s not necessarily or even primarily from the government … It’s from self-censorship; it’s from people who are afraid to engage because of what will happen to them if they do.”

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is on at Carriageworks, Sydney, on August 24 and 25.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout