Anthony LaPaglia stars in Death of a Salesman in Melbourne

Every note rings true in Neil Armfield’s production of the Arthur Miller classic, with an exceptional cast led by Anthony LaPaglia.

In the decade and a half since his boys left school, Willy Loman has been in a race with obsolescence. A race with the junkyard. “Once in my life,” he roars, “I would like to own something outright before it’s broken!”

At 63, Willy is also in a race with the graveyard. The travelling salesman has lost his edge, lost his base salary – he’s eking out a living on dwindling commissions – lost his will to survive and, maybe, lost his mind. He has conversations with his dead brother and with youthful incarnations of his grown-up sons.

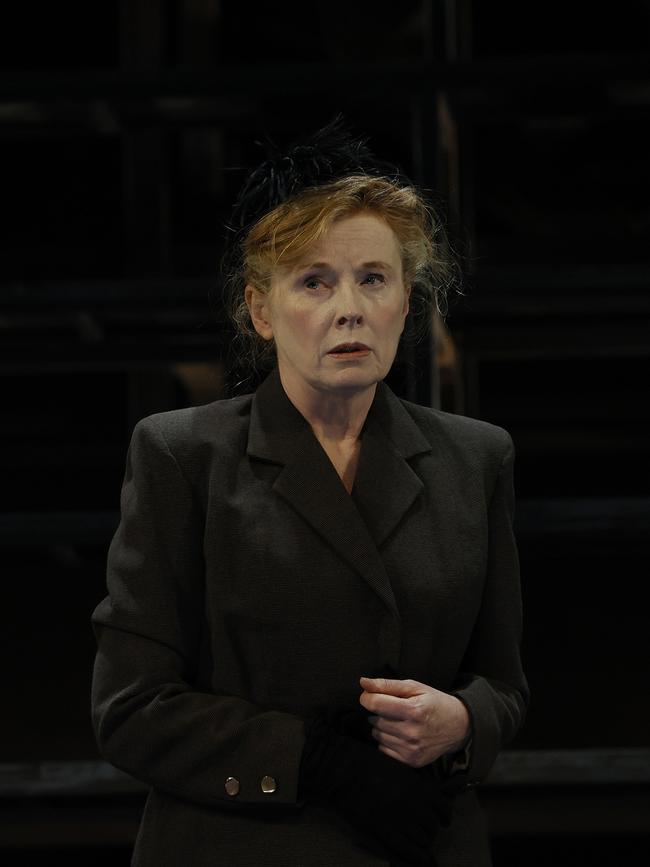

Willy (Anthony LaPaglia) presides over an empty nest with his infinitely patient wife, Linda (Alison Whyte). They have just one more payment to make on their 25-year mortgage. Then they’re free and clear. But Willy believes he is worth more to his family dead than alive.

Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman is regarded as a critique of the American Dream and an account of the psychological costs of post-war US capitalism. Real success, it seems, is as approachable as a mirage. Or it is, at least, for Willy and his sons, Biff and Happy, who had the misfortune of being popular and successful at school. Everything since the age of 17 has been a disappointment.

Biff (Josh Helman) flunked “math” and so missed out on multiple football scholarships. He is aimless and self-destructive, a “buck-an-hour” kleptomaniac. Kid brother Happy (Sean Keenan) – according to their long-suffering mum – is a philandering bum. In a shit-kicker job. They’re an unsympathetic lot. An Old Testament god might have snuffed them out. (Miller can’t be accused of romanticising the working classes.)

What shines through in Neil Armfield’s authentic, uncompromising, unrushed and unabridged production is just how formally ambitious Miller’s play is. The past and the present, the young and the old, the living and the dead all coexist. “Everything we are,” wrote Miller in his memoir, Timebends, “is at every moment alive in us.” The past is merely a “dimmer” version of the present.

The action takes place not in the family home, but on – and in front of – the bleachers of Ebbets Field, scene of young Biff’s triumphant tryouts. The tiered seating is like the crumbling scaffold of Willy’s dream: the skeleton of lost youth and lost hope. To offset the abstraction of the staging – and the artificiality of having the ensemble watching on – the acting is persuasive and impressively natural.

LaPaglia is more Fredric March (the first on-screen Willy) than Lee J. Cobb (the first onstage Willy) – more mad than modulated – but his volcanic Fred Flintstone grouchiness is buttressed by the agility, clarity and finesse of the actors around him.

Whyte is a devastating and devastated Linda. Richard Piper’s cameo as Willy’s adventurer brother, Ben, is impressively weighty. He’s like a slain warrior brought to Valhalla, still and authoritative. Helman, Keenan and Tom Stokes (as Bernard) show great range. Even the smallest roles are nailed.

It’s exceptionally rare for a period piece with American accents not to sound false and look stagey, but one could imagine this production being filmed and successfully screened in cinemas like a National Theatre Live production.

And, it must be said, it is almost miraculous that commercial theatre producers – without the safety net of a subscription audience – should tackle a large-cast play such as this so seriously, and so well. Armfield’s production is as satisfying as a good book, read start to finish in a single sitting.

Tickets: $69-$179. Bookings: 1300 795 012 or online. Duration: 3hr 20min including interval. To Oct 15.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout