Spotting tomorrow’s stars at NIDA

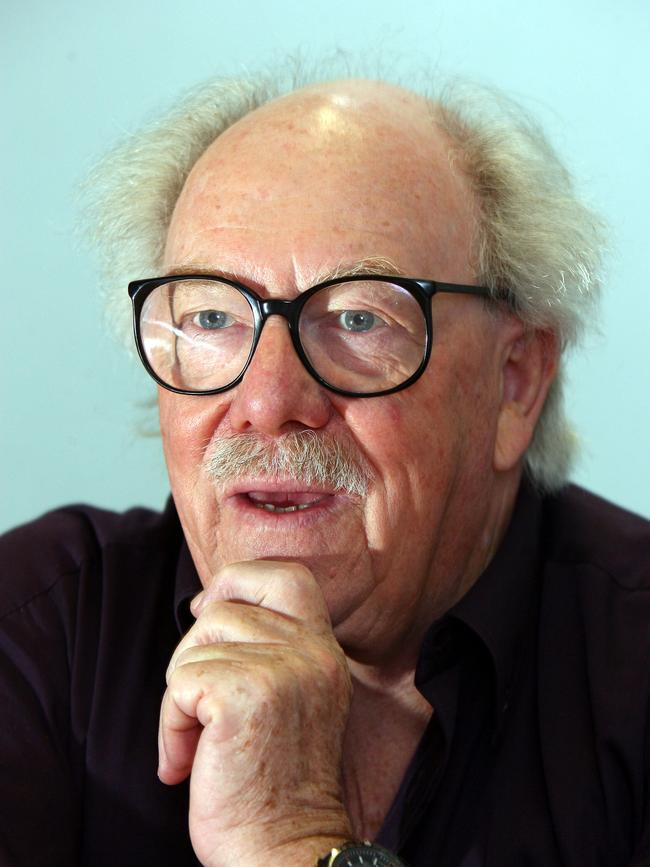

Cate Blanchett made it, Rachel Griffiths missed out. John Clark reflects on sitting through 20,000 auditions at the National Institute of Dramatic Art.

“What do you look for in auditions?” I was often asked. The simple answer was exceptional talent. At the National Institute of Dramatic Art there was never a fixed view of what an actor should look like or sound like, what theatre work they should have done or what academic qualifications they required. Talent comes in all shapes and sizes, from every kind of background, literate or dyslexic, large or small, beautiful or plain.

When a person walks out on stage and starts to walk, talk and think some other person’s words convincingly, you pay attention. If you are compelled to watch, to listen, to be drawn into their story, to share their experiences, you become aware of good acting. When somebody can repeat this magic with a different story and then with another, you know you have exceptional talent.

I was also asked, “Did the great actors stand out when they auditioned?” Maybe a few but, generally, no. The system was not foolproof. We failed to detect the exceptional talent of Rachel Griffiths, who auditioned in Melbourne with Cate Blanchett. Rachel has made an impressive international career and talks about her audition with grace and good humour.

The press have often pointed to Anthony LaPaglia as a powerful actor who slipped through the net. In fact, we admired his audition but he was too young at the time so we suggested he re-audition the following year. In the event he did not require NIDA’s assistance.

My predecessor, Tom Brown, offered a place to Gai Waterhouse but she declined, preferring to become a successful racehorse trainer. I still meet people in the profession and in my social life who tell me, “I auditioned for you many years ago, but … !”

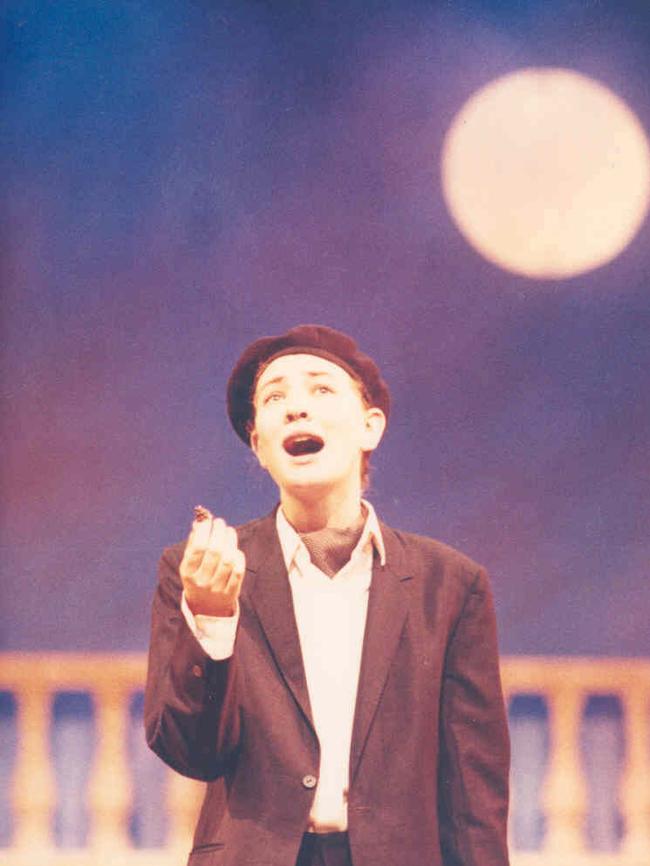

Even by the end of the course it was not possible to predict who would become stars. Some of our in-house predictions were right, others completely wrong. One 1991 review of a production of Twelfth Night declared, “There are no stars among this year’s graduates.” The cast included Essie Davis and Blanchett. There are too many fine graduates who have not managed to create their own luck in the industry and some we thought indifferent students have come into their own as soon as they escaped from NIDA.

Every November, as the teaching year ended, I was asked, “What are this year’s graduates like?” The answer was always the same: I’ll tell you in five years. We were content to leave the cultivation of stars to hard work, good fortune and time.

Despite our best efforts, auditions were not always trouble-free. Some of the mishaps were surprising.

In Sydney there was a girl who asked if she could use a couple of props in one speech. We replied, “Of course”, so she moved to the centre of the room with a large bag, opened it and extracted a brick, a hammer and a large cat with a dog’s lead around its neck. She placed the lead beneath one foot to secure the cat while she arranged the brick on the floor and took up the hammer in one hand. There was an appalled silence in the room that was finally broken when the terrified animal jerked free and, with the lead still attached, hissed and fizzed around the room and leapt out the window – probably to be scraped off the tyre of a passing motor vehicle in High Street.

I must have seen more than 20,000 auditions but sadly it is the worst, not the best, that stay in the memory. There were auditionees who could scarcely get the words out, while others were supremely confident. I asked one young lad which Shakespeare speech he was going to do. “Hamlet, Prince of Venice,” he said. Denmark, I corrected him. “Yeah, that’s the one … ‘To be or not to be …’.”

Sometimes the problems were more serious. One girl made a good attempt at a speech from Romeo and Juliet in which Juliet eagerly awaits Romeo’s arrival so he can “leap into these arms” and consummate their marriage, but she could not reveal Juliet’s excitement and impatience. A staff member asked her to relate the speech to her own experience, perhaps waiting for a boyfriend running late for a promised meeting. She did not respond either to this direction or to several others and ultimately was not offered a place.

Some months later we were advised by the South Australian anti-discrimination commissioner that a complaint had been lodged on the grounds that a young actor had been asked questions about her personal life that were not required of other applicants. The problem stemmed from a fundamental misunderstanding about our work in the theatre. An actor’s personal life is the raw material from which they fashion their performance – it cannot be left out of the process. Eventually the commissioner came to Sydney, with her solicitor, and demanded a private meeting with the offending staff member.

Anticipating this, I had the University of NSW solicitor and the entire acting staff standing by. When the commissioner arrived, I advised her that, as we all conducted auditions, if something untoward had occurred we wanted to learn from it. The commissioner reluctantly agreed.

John Clark began teaching at NIDA in 1960 and was director from 1969 to 2008. His memoir An Eye for Talent: A Life at NIDA is published today by Coach House Books (336pp, $40).