Seeing his land with the speed of light

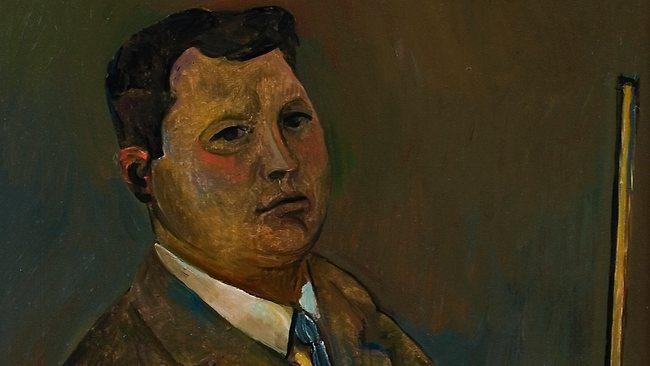

FRED Williams was an artist who would paint only in Australia, nowhere else, because he knew it well.

AT the media preview for Fred Williams: Landscapes of a Continent at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1977, Williams said: "I will never paint anywhere but in Australia because I know Australia . . . It would be impossible for me to paint anywhere else. I must be inside looking out, not outside looking in."

Here he was on his first visit to the US, having just turned 50, looking at his own exhibition at MoMA: the first solo show of an Australian artist at that institution that houses the works of some of the great European modernists he had admired over the years.

The exhibition included a substantial showing of his gouaches, emphasising his strengths as a painter in this medium.

Also on display in the museum for the first time was the installation of Henri Matisse's The swimming pool, 1952 (acquired by MoMA in 1975), a paper cut-out mural that had covered the walls of the artist's room in Nice. A museum brochure described Williams as "another artist who draws with colour". In his work, landscape was clearly a focus but abstract qualities were also evident to those who saw the gouaches for the first time.

The opening night was a special occasion. Robert Hughes, then writing for Time magazine, was there and subsequently made a short film of the exhibition.

True to form Williams did not especially enjoy the limelight of the media preview (preferring the works to speak for themselves), although several reports convey his excitement about the exhibition and underlying confidence at this point in his artistic life.

The American commentaries were engaged and enthusiastic. Thomas B. Hess, editor of the journal Art News and art critic, remarked: "There are allusions to 19th-century topological documents by explorers in some landscapes that come in stacked, horizontal bands, and everywhere is the explorer's wandering eye as he comes upon a vision as old as earth, as if seen for the first time."

Critic and art historian John Russell wrote in his weekly round-up of exhibitions in The New York Times that it was evident that Australian artists had "a treasure house of strange images and unforeseeable colour" to draw upon.

Several months after returning from New York, on October 25, 1977, Williams was eating pawpaw for breakfast in Weipa in tropical far-north Queensland. "[They are] grown here and they are quite perfect." It was here that he had his first really extensive view of the land from a light aircraft.

He had long conceptualised the viewpoint that this experience might afford. In the 1960s, in the front of one of his cuttings books, he had pasted a newspaper clipping of a light aircraft flying over a landscape with bushes dotted across the landscape below.

Such a flight had been planned in the past but for several reasons it never happened. Now, in 1977, he finally had the opportunity. The experience of flying low over the country was just as brilliant as Williams had always hoped it would be and he later painted innovative gouaches such as Weipa shoreline, 1977, in which a swathe of vibrant blue dominates the composition with a narrow strip of coast at the very top.

Among the most outstanding gouaches to come from Williams's visit to Cape York visit are Weipa I-IV, 1977. In these strip paintings the colours of the earth are given full resonance: reddish ochres veering to soft glowing pinks, dark to sandy browns and warm mustard yellows.

Williams was fascinated by geology and there was a special correlation between the strip format and the Weipa terrain. If his Queenscliff beachscapes painted six years earlier summed up the luminescence of the coastal experience, Weipa I-IV gave painted substance to the richly coloured earth of the far north, laying the groundwork for the Pilbara series later on.

In 1977, Williams also spent time working in the Victorian landscape, painting oils in the open, followed by studio versions of the same subjects. Among the most important of these was the aptly named Wild Dog Creek. Here Williams paints the landscape with great verve, interweaving thick and thin areas of paint, quick and slow brushmarks, at times in dots and dashes indicating small stones and plant life.

It is like his early paintings of trees that don't appear anchored in the soil, except now the thin trunks almost seem to be taking off, as though a gust of wind would sweep them and all the loose bits of surrounding bark into the ether.

Rather than attempting to paint running water in a literal way, the luminous creek becomes a focal point, a space for reflection. It is also a surreal element in the way that it is outlined to form a strange abstracted shape.

Williams enjoyed this strangeness and returned to the idea in his Waterfall polyptych, 1979, the magnum opus of the group of late waterfall paintings. He remarked that when painting the preliminary, smaller version of the waterfall outdoors at Lal Lal Falls near Ballarat, he had decided to do two paintings in the light of morning and two in the afternoon.

All were painted on the one day as the light changed. As he shifted vantage points, he became aware of the metamorphosis of shapes. These four canvases were taken back to his Hawthorn studio, "put aside for six months until the paint hardened". The drying time also gave him the opportunity to mull over his new discoveries.

On March 23, 1979, Williams worked hard all day in the studio. "I start early on the Lal Lal four-panel one. Work virtually without stopping for some eight hours. They are all partly on -- but not quite at full underpainting stage! A monumental effort was required from me here today . . . One of those days that I wish happened more often -- but I only have ideas like this through intense observation and work."

As the painting progressed he variously built up the surfaces and simplified forms, especially in the third and fourth panels, with a touch of "acid green at the bottom of the lake" in the last.

He was mindful of the interrelationships between the four parts, enjoying the interactions and fluctuations across the work in the dark shapes and the mutability of the surrounding luminous landscape of warm and cool colours.

These variations on the same subject have a symphonic quality of ebb and flow, of small notes leaping above the dominant register and of the powerful impact when the parts come together as one majestic whole.

Edited extract from the exhibition catalogue Fred Williams: Infinite Horizons. The exhibition is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, until November 6.