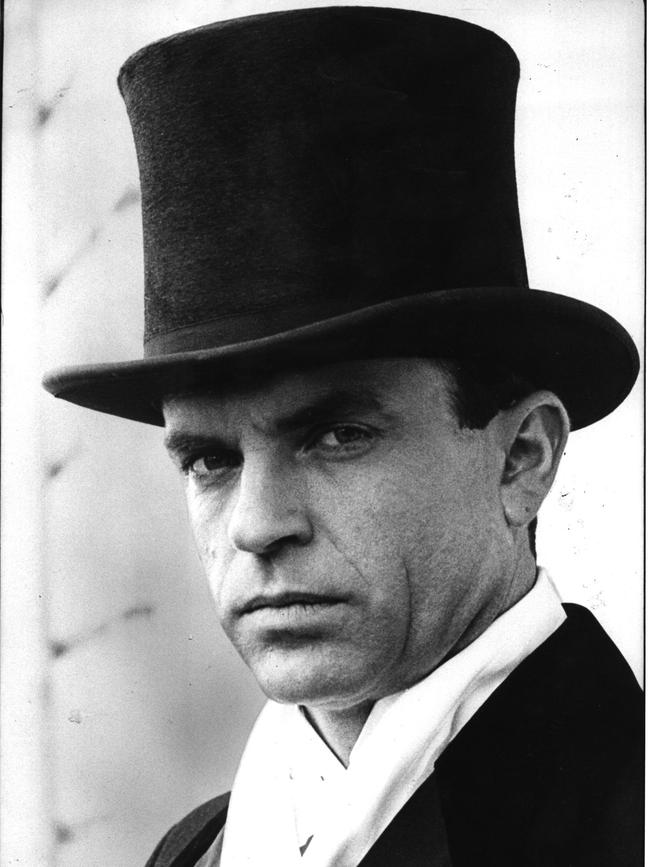

Sam Neill stars in Foxtel legal drama The Twelve

Sam Neill gets the measure of some of the great actors he’s known and worked with, from James Mason to Peter O’Toole and Mel Gibson.

Sam Neill is one of the best-known actors from this part of the world – he’s a Kiwi but he has an Australian base – and we’ve been watching him at least since he made My Brilliant Career with Judy Davis.

At the moment you can watch him as a wily and urbane barrister in The Twelve in which a jury has to weave its way through the complexities and smokescreens of a riveting thriller plot. Kate Mulvany is the accused, charged with killing a teenage girl whose body has never been found.

Neill can also be seen in yet another instalment of the Jurassic Park franchise – Jurassic World Dominion – the dinosaur shocker Steven Spielberg started decades ago.

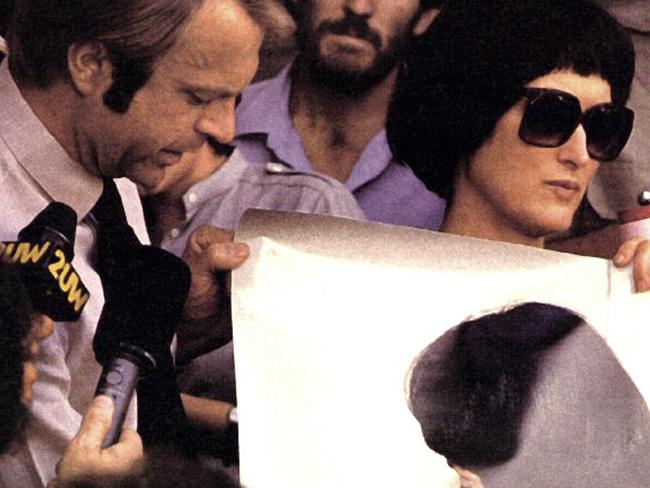

But we have seen Neill as everything from that dashing gentleman bushranger Captain Starlight in Robbery Under Arms to Michael Chamberlain in Evil Angels, Fred Schepisi’s film of John Bryson’s devastating demolition of Lindy Chamberlain’s murder conviction, opposite Meryl Streep as Lindy.

He was born in 1947 in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, but his father was a New Zealander of the toffiest kind. “He was,” Neill says, “very sort of British by disposition. He was Harrow and Sandhurst”, having attended one of England’s classiest schools and then the famous military academy.

In fact, Neill came from a long line of gentlemen soldiers, but tried to disguise his upbringing when the family moved to New Zealand.

“You arrive in New Zealand with a posh accent and that marks you out right away – not in a good way,” he says.

“I think the telling thing is, at the age of 11, my best friend and I, we changed names. I think that tells you a lot – actually adopting a sort of persona, in a sense, and there’s something performative about that. I think that’s where you see the origins of an actor.”

At school he did Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and he played the first tempter in TS Eliot’s verse play, Murder in the Cathedral, the one who talks to Thomas Becket, the archbishop soon to be martyred, about how “love in the orchard” can “send the sap shooting”.

He majored in English literature at university but says he could never have become an academic. He was too interested in doing plays and debating and going on political demonstrations at the height of the Vietnam War. He’s stayed a lefty of a mild-mannered kind. The one moment his voice booms with passion is when he talks about boat people.

“People are short of labour,” he thunders in what sounds like a great actor’s voice. “You can’t get a barista, you can’t get a nurse. The first person I’d give a visa to is someone who has (come by boat) – they are the people who want to contribute. They want to do right by their family, they want to do right by their country, and to throw them into jail is just completely nuts.”

At other times, Neill is very intent on setting the record straight, and is a bit tentative in a way that’s very likeable but is in great contrast to the easy urbanity of the QC he plays in The Twelve, and to his steely understatement as Reilly, Ace of Spies in the British TV series.

We’re ticking off the plays he did at university when he says, invoking the curse in the instant of avoiding it: “I played Macbeth in the Scottish play.” Could he rattle it off now if someone put a gun to his head?

“No, I just remember little snips and pieces, you know – ‘the crow makes wing to the rooky wood’.”

He was directed as Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream by the famous crime writer and director, Ngaio Marsh. “Dame Ngaio, in fact,” he says expressionlessly.

“I was just thinking about that the other day. She spent half the year in New Zealand and half the year in England. She was rather grand and posh, Ngaio, and she was a friend of Gielgud’s and all that lot. She directed us like plummy Poms and she was a fearsome woman, Ngaio. She always wore a beret and smoked a pipe.”

Neill caught the attention of another famous figure who had played everything from Humbert Humbert in Kubrick’s Lolita to co-starring with Judy Garland in A Star is Born. There is a legend of James Mason’s fascination with Neill, which presumably sprang from a sense that he was the same kind of actor. Here’s the story in Neill’s words.

“Well, James was inordinately kind to me. I was in Melbourne doing an ABC thing called Lucinda Brayford (from the Martin Boyd novel) with Wendy Hughes. And there was a call on the sound stage. No one ever calls you on a sound stage. And the assistant came up and said, ‘There’s a phone call for you’.

“Anyway, this voice said, ‘Hello, I’m James Mason, and my wife and I think you’re an interesting young actor, and I know a bit about you, but I think you should be working abroad so I’m sending you an air ticket. So when you’ve finished your job, whatever it is, please come to Europe, and stay with us and meet my agent in London’. And I said, ‘Thank you very much. How surprising and how very kind’.”

Neill says Mason wasn’t a model for him, even though “I was always much more taken by English actors than I was by American ones and, I suppose, you know, James was one of those”.

To his father’s relief, Neill worked for eight years for Film New Zealand before he came to Australia to make it as an actor. Mason came out of the blue.

“I went to Europe and I had a great week with them. They lived up the road from Charlie Chaplin, not far from Geneva, and I met his agent, and that agent took me up for a film and I ended up taking a role in the third Omen film. So all that happened rather rapidly and then I decided to settle in England and plug on with this” – he laughs slightly at the thought – “newly found career as an actor.”

So why didn’t the man with the highest possible Antipodean accent – accentless in terms of the tonier reaches of Australian and New Zealand English – go on the English stage, given that he had the polish of someone with English training?

He chuckles, almost bewildered at this. “I really wasn’t interested in being on the stage, I was just really interested in cinema. And the idea of having a six-month run in the West End filled me with dread, to be honest.

“Nor did America beckon, very attractively. I wasn’t interested in going to LA and living there. I went and had a look a couple of times but I didn’t really take to it. My life was always peripatetic but based in New Zealand and Australia. I was persuaded to take my family to LA for a while and we were there for a year or two, but the longer I was there the more determined I was not to bring up my children there.”

Geoffrey Rush describes Neill as a leading man.

“That leading man thing is something I pondered as well. I wouldn’t necessarily appoint myself with that title but there are actors that suit that description who can carry a film or a play and perhaps that’s what distinguishes some actors from, say, character actors. But it’s a big ask, isn’t it? To carry a film.”

He laughs and it’s difficult to know whether it’s self-doubt or the risk of sounding immodest.

“And I’ve never known if I had that capacity but I see it in others. I remember doing a little film with Mel Gibson and the first thing you could see was this guy was a leading man. He could carry a film effortlessly. And I think it’s something to do with the way you want to watch them, you don’t get tired of watching them. It’s that watchability.”

Although he sidesteps the description of himself as a leading man, he admits it the next moment. “In Reilly, Ace of Spies, I had to carry 12 hours of that and that’s a big ask for a leading man. And I was acting with British actors I’d admired. At that stage in your career you’re not entirely sure if you’re as good as them. What was great about the experience – and it was a relief for me – was that I wasn’t better than them, but I was as good as them.”

He’s acted with some of the biggest actors in the profession, such as Peter O’Toole. “Look, I’d known O’Toole since 1980 and I dearly loved him. But the thing I learnt from him more than anything wasn’t from anything he told me but just by watching him – and it’s so contrary to what young actors do these days, which is mostly mutter their lines, and the more indecipherable they are, the more realistic it’s supposed to be. Peter never wasted a word. It was a treat for him. There was no such thing as a throwaway line for him. Why throw away a line? Get the most (out) of every line. And that was really refreshing to watch.”

So the voice of the QC in The Twelve is his own voice, is it? His response is almost sardonic. “Oh well, perhaps it is,” he says. “I was more thinking of a couple of friends I have who are QCs in New Zealand and they have that kind of wry thing about them, as well as being what used to be called clubbable. And I had them in mind when I was addressing that role.”

Neill talks of how John Clarke taught him how to pass a symbolic logic exam in philosophy in a bare two hours, and how Bryan Brown calls him a “posh bodgie”. He is clearly haunted by his military background.

“I would have made a hopeless soldier but the idea of service interests me and I think there’s something in the blood,” he says.

“I also had Quaker forebears as well. There’s quite a bit of pacificism that runs the other way. So, you know, it’s not all one way.

“My grandfather, who became a major general, was a very highly decorated soldier and came from a Quaker family. When he told his father he was going to become a soldier, he said, ‘Charles, thou art a man of blood’ – that was his last word on it.”

He laughs again. “Look, I still idolise my father and he was on the right side of history. There he was, fighting fascism.”

Neill says he watched a lot of war films as a young boy. “The Dambusters. I can still whistle the tune,” he says, and cackles. Then he tells me that he’s just made season six of Peaky Blinders, where he plays a pretty ghastly Ulsterman.

“He’s the most horrific character, so four-dimensionally horrible that it’s just tremendous fun. I’ve played a few bad characters but there are a couple of things I try to give them. First, a slightly comic dimension,” he laughs with pleasure. “But the second thing is I try to feel sorry for them. They’re slightly damaged people. Something horrible has happened to them, they have their reasons. Every villain has his reasons.”

It’s a characteristically charitable perspective from this man born to a long line of soldiering folk who is in various ways more shy and more thoughtful than a lot of his histrionic brethren.

Neill is a paradox because he understands the ethics of the “perfect gentle knight”, in Chaucer’s phrase, but he is also impassioned about the superiority of women and the fate of the insulted and the injured, those who seek refuge.

He has a beautiful voice that registers every bit of unease or torpor almost as if he had no control over it – yet he is the most considerate of interviewees.

As an actor, he has a precise sense of the camera. You know the command and music of the voice, the handsomeness of the face. But he is such a reluctant leading man.

The Twelve is screening on Foxtel.