Richard Chamberlain, star of Dr Kildare, dies at 90

Chamberlain became an instant favourite with teenage girls as the compassionate physician on the TV series that aired from 1961 to 1966.

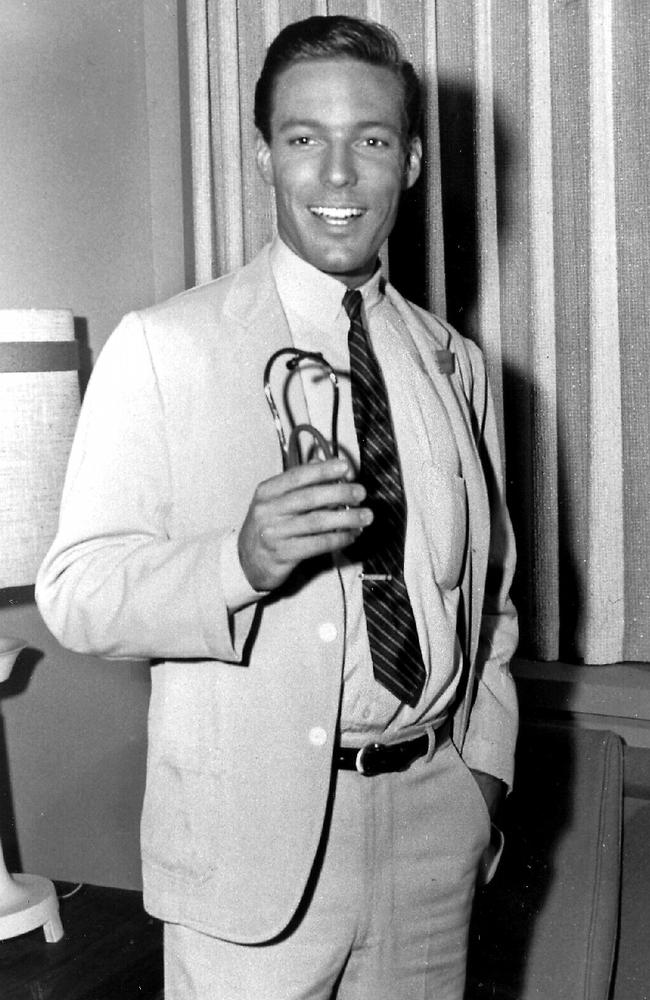

Richard Chamberlain was in his mid-20s and had little acting experience when MGM cast him as Dr James Kildare, the earnest young intern with the polished bedside manner, in the medical series that became one of American television’s biggest successes of the 1960s.

Tall, slim and good-looking, Chamberlain was turned into a heart-throb overnight by Dr Kildare. The studio proudly declared that the 12,000 letters he was receiving a week – almost exclusively from female fans – was a record and more than Clark Gable had received at his peak.

Chamberlain’s boyish innocence as Dr Kildare was offset by his gruff superior, played by veteran Canadian actor Raymond Massey. The series ran for six seasons, notching up almost 200 episodes, and although it turned him from a bit-part actor into an international star, Chamberlain found it hard to escape its shadow.

The role, he felt, typecast him as bland and lightweight, his success based more on his looks than on the depth of his acting. When the series ended in 1966 his relief was palpable and, turning his back on the Hollywood studios, he announced his intention to concentrate on the stage in an attempt to establish himself as a serious actor.

However, his fears that the public was not ready to let him move on seemed justified when his Broadway debut in a 1966 musical adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, with Mary Tyler Moore, was an unmitigated disaster. The show closed before it opened after a handful of ill-received previews.

“Turned out to be the biggest flop that ever hit Broadway,” he noted ruefully. He assuaged his disappointment by acting in stock company productions of The Philadelphia Story and Noel Coward’s Private Lives and touring in West Side Story.

He then found refuge in Britain, where he spent many years in the late 60s and early 70s in an effort to put Dr Kildare behind him and expand his horizons. He impressed as Ralph Touchett in BBC television’s 1968 adaptation of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, a performance he later discussed with Queen Elizabeth II when introduced to her at a film premiere. “Oh yes, we watched that,” she told him before adding: “Well, not all of it.”

He supported Julie Christie in Richard Lester’s film Petulia and was a tortured Tchaikovsky in Ken Russell’s extravagant but tasteless The Music Lovers alongside Glenda Jackson, and after intensive voice coaching was ready to take on Shakespeare, playing Hamlet at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. “Anyone who comes to this production to scoff at the sight of a popular American television actor, Richard Chamberlain, playing Hamlet will be in for a deep disappointment,” a review in The Times pronounced.

There were further heavyweight stage appearances including a revival of Christopher Fry’s verse comedy, The Lady’s Not for Burning, at the Chichester Festival, and he played Aramis in Richard Lester’s 1973 film The Three Musketeers and reprised the role in its sequel the next year.

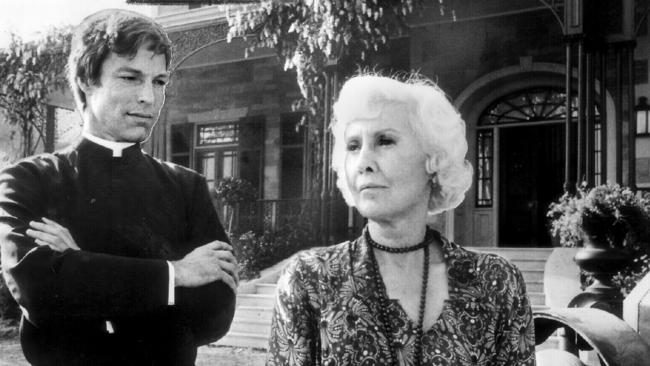

His return to Hollywood came in 1974 disaster film The Towering Inferno but he built on his new serious image by playing the Prince of Denmark on US TV and taking the title role in Jonathan Miller’s stage production of Richard II. He also triumphantly made his full Broadway debut in Tennessee Williams’s The Night of the Iguana in 1975. With his reinvention complete, he went on to become the king of the TV miniseries. Among the more notable was Centennial (1978), based on James Michener’s novel, and Shogun (1980), from James Clavell’s novel, a handsome journey through 16th-century Japan in which Chamberlain played an English sea captain who is captured and brought before a war lord. However, both were upstaged, at least in Britain, by The Thorn Birds, based on Colleen McCullough’s story of an Australian Catholic priest, Father Ralph, played by Chamberlain, who abandons his vow of celibacy for an affair with a young woman, played by Rachel Ward, who gives birth to his son.

The Thorn Birds was a high point in Chamberlain’s later career and won him a Golden Globe as best actor, his third such award after similar citations for Dr Kildare and Shogun.

For decades Chamberlain was reticent about his private life. Fearing that coming out as gay would alienate his mostly female fans and damage his career, he simply refused to respond to the rumours. Even after he was outed by French women’s magazine Nous Deux in 1989, he maintained his silence until the publication of his memoir Shattered Love in 2003, when he confirmed that he was gay.

“When I grew up, being gay, being a sissy or anything like that was verboten. I disliked myself intensely and became ‘Perfect Richard, All-American Boy’ as a place to hide,” he said. “Over a long period of time, living as if you were someone else is no fun”, but coming out “was like an angel had put her hand on my head and said, ‘all that negative stuff is over’ ”.

It transpired that he had been in a relationship in the early 70s with actor Wesley Eure, almost 20 years his junior, and in 1977 had begun a long-term relationship with Martin Rabbett, another much younger actor. They appeared together in the 1986 film Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold and set up home together in Honolulu, where Chamberlain took up painting seascapes. He moved back to Los Angeles in 2010 when he and Rabbett separated but they remained close friends.

George Richard Chamberlain was born in 1934 in Beverly Hills, California, the second son of Elsa (nee von Benzon) and Charles Chamberlain, a salesman.

His interest in acting was piqued at Pomona College, where he took a degree in art, and he was on the point of signing with Paramount Pictures in 1956 when he was drafted into the army and posted to Korea, where he spent 16 months as an infantry company clerk and detested every minute of it. On his discharge he took classes at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music and Drama, paying for his studies by working variously as a chauffeur, supermarket clerk and construction worker.

In 1959 he landed his first screen role with a bit part in an episode of TV western Gunsmoke.

When MGM put him under contract, the first role he was assigned was Dr Kildare and it led to a parallel singing career. He had a top 10 hit with Theme from Dr Kildare (Three Stars Will Shine Tonight) in 1962 and enjoyed further hits with Love Me Tender and All I Have to Do is Dream.

In later life he continued to enjoy the stage as much as the screen, in 1987 appearing in the first revival on Broadway of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit since its premiere in 1941. He also appeared as King Arthur in the touring version of Monty Python’s Spamalot.

Liberated by no longer having to keep his sexuality a secret, he went on as an out and proud gay man in his 70s to play several gay characters in TV episodes of Will and Grace, Brothers and Sisters, and Desperate Housewives, and in the 2007 film I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry.

The Times

Dam observations with Dr Kildare

BY ALAN HOWE

Late in February 1985, I found myself in Harare on a last-minute holiday before returning to Australia after five years in London on The Times.

I had, days earlier, signed on to be news editor of The Australian. I stayed with a friend’s brother in the city. We drove around for a few weeks in a borrowed car and had adventures I can hardly believe we survived. Shot at. Jailed briefly in Zambia as spies. And other frightening episodes that still raise the hairs on the back of my neck.

As my fortnight in Africa drew to a close, I stayed in Zimbabwe’s capital hoping nothing else would happen. I had just a few days left. I went to the Zimbabwe parliament to see former Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith in action. He was still a member. I stood in a queue for some time but when I got to the door I was refused entry because I didn’t have a tie.

Coincidentally, days earlier, fleeing a car of locals who had shadowed my movements for days, I drove for kilometres to the Masvingo Zimbabwe Sun hotel, which, I believe, had been Cecil Rhodes’s house at one point.

I drove with relief into the compound, itself far from any humanity. At the door there I was greeted by a young bloke in a crumpled shirt and jacket. I told him that I would like to have dinner and perhaps to stay for the night. I could stay the night but dinner was not on the cards. I didn’t have a tie.

The place was empty. Mine was the only car in the carpark, such as it was. But rules were rules.

Did I mention that it rained heavily almost every day I was in Zimbabwe? Anyway, with 72 hours to go, I heard on the radio that a dam outside Harare that had been years in the making was about to overflow and that the spillway would be a perhaps spectacular scene. Why not?

I drove there and was soon among the thatched huts of village life in Africa. I had crude instructions and they got me there, eventually.

As I turned down the little bush track to the dam, but still some kilometres away, I chanced upon three casually but well dressed Westerners walking in the same direction. Hearing my car engine, they went into single file to let me pass. Intrigued by who they might be, I looked back as I passed and stopped suddenly. I jumped out. “You are Dr Kildare!” I said to the bloke in the middle, forgetting at that moment that his name was Richard Chamberlain. “My mum loves you.” He told me he was in there shooting a remake of King Solomon’s Mines, that I am assured was a dud.

A day later he was there again in the Monomotapa Bar in Harare. I said g’day, but he was with a group of Americans and I let him be. I was struck, though, by the beautiful blonde at his side. And so passed my only opportunity of meeting Sharon Stone.