World’s deadliest disease: could it happen again

The 1918-19 flu epidemic killed more people than World War I. Could it happen again?

A succession of World War I centenaries have been commemorated during the past four years, but there has been much less attention paid to another equally important centenary. In 1918-19, an influenza pandemic swept the globe, killing an estimated 50 million to 100 million people, far more than had died in the preceding four years of war.

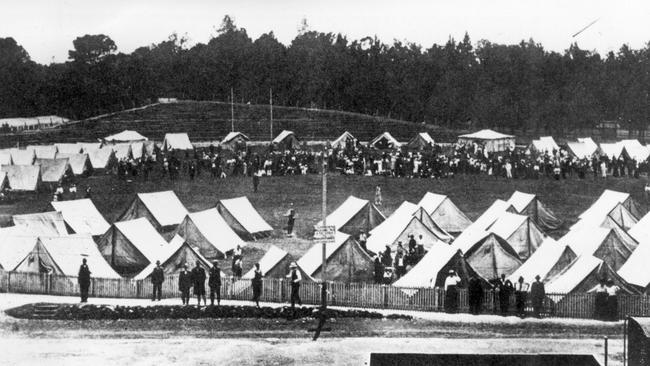

The pandemic reached Australia in early 1919 as servicemen and women returned from the battlefields of the northern hemisphere, bringing with them the most lethal influenza virus the world has known. The fatality rate here was lower than elsewhere, but 40 per cent of the population fell ill and an estimated 15,000 people died.

In Influenza: The Quest to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History, American emergency medicine researcher Jeremy Brown traces the dramatic history of that pandemic and subsequent outbreaks:

The story of the twentieth century can be told through its wars or its technological leaps — or through its flu pandemics. The outbreaks were irregular in timing, as with all of recorded flu history, but they were familiar in progression: a point of origin, a rapid spread, sickness and death, and a furious public debate about how to respond.

Influenza has long resisted our best efforts to understand it, largely because of its remarkable capacity to reinvent itself. The virus “throws a wrench into our elegant system of defences because it is a shape-shifter”, Brown writes, describing the constant transformations from genetic mutations or hybridisation between different human or animal strains.

Because we’re unlikely to encounter exactly the same influenza virus twice, our immune systems are permanently on the back foot. Antibodies to one year’s flu won’t help fight off the following year’s virus. For scientists designing vaccines, it’s a constant game of catch-up as they try to predict six months ahead which strains will dominate in an upcoming flu season.

Hanging over their research efforts is the ever-present fear of a future pandemic on the scale of 1918. Could it happen again?

In an attempt to answer that question, scientists have gone to heroic lengths to decode the secrets of the virus generally referred to simply as “1918”, including digging up bodies of its victims from the Arctic permafrost to extract and isolate the pathogen.

Despite such efforts, the 1918 virus continues, in true flu style, to resist our investigative efforts. We still don’t know, for example, why it was particularly lethal in healthy young adults.

One thing Brown does make clear in this thorough, engaging analysis of influenza is that we can’t afford to ignore the lessons of the century-old pandemic: “we have not done enough to place the 1918 pandemic in our collective consciousness … What changes our vigilance about a disease is our capacity as a society to understand its impact, what it has done in the past and how it might affect us in the present.”

In the fight against infectious disease, the mapping of outbreaks has long had an important part to play, which makes a historical atlas of disease a potentially fascinating book. In The Atlas of Disease, British journalist Sandra Hempel has gathered historical information about several infectious disease outbreaks, illustrated by maps showing their origins and spread.

The book includes the map of London’s 1854 cholera outbreak produced by physician John Snow. Through charting the houses where deaths had occurred, Snow was able to narrow the source of the outbreak to a particular water pump in Broad Street, Soho. His research demonstrated that cholera was a waterborne disease rather than being caused by the “miasmas” thought until that point to be responsible for most epidemic disease.

This is a handsomely produced book, but unfortunately the content is not as impressive as the production values. The rather plodding text is accompanied by maps that, although specially commissioned, are short on useful information. There is little explanatory detail and no signpost to data sources, making them little more than colourful illustrations.

Some of the maps are confusing if not downright misleading. One shows the spread of syphilis from 1492, when the Christopher Columbus expedition is believed to have brought the disease to Europe from the Americas. According to this map, the disease then spread to Australia in 1520, which seems improbable given the lack of European contact with the southern continent at that time. Another map appears to show the number of malaria cases in Australia in 2016 to be in the one to five million range. Australia and New Zealand are the only two Western countries shown to have such a high incidence of the disease. For the record, Australia experiences about 500 cases of malaria each year, most of them brought in by travellers. Given the lack of information provided in the book, the only explanation I could see was that the numbers for Australia and New Zealand might have been combined with those for Papua New Guinea, which has experienced an increase in malaria cases in recent years.

If so, that is a serious misrepresentation of the global burden of ill health. When a wealthy country such as Australia is shown as having a high incidence of malaria, it obscures the fact this is overwhelmingly a disease of the global poor and, as a result, one that has not been the target of the research effort it deserves.

Another health scourge that disproportionately affects those from less wealthy countries is air pollution, the subject of Gary Fuller’s The Invisible Killer. Fuller, a British air pollution researcher, makes it clear he considers pollution a justice issue, not just a technological or environmental one:

There are huge injustices at the heart of the air pollution problem. By using our air to dispose of their waste, polluters are destroying a shared resource and avoiding the full cost of their actions. They leave all of us who breathe poor air to pay the price through our health and taxes.

Air pollution was not widely recognised as a health problem until the 1950s, Fuller explains. In fact, for centuries smoke and fumes had been considered a healthy antidote to the miasmas considered responsible for outbreaks of disease.

In his book on influenza, Brown makes a similar point, noting how some English parents during the 1918 pandemic took their sick children not to hospital but to the local gasworks to inhale the fumes.

London’s notorious fogs — the “pea-soupers” immortalised in the tales of Sherlock Holmes — were caused by water droplets in the air combining with soot and sulphur emitted by the burning coal that powered the city’s industry and kept its citizens warm.

In the first half of the 20th century, the resulting smog was sometimes so bad that cinemas would be forced to close because the air pollution inside the movie theatre made it too difficult for patrons to see the screen.

What eventually galvanised action against London’s toxic air was the extreme smog of the winter of 1952, described by Fuller as “the UK’s greatest peacetime disaster”. So many deaths were reported after the peak pollution weekend that authorities initially assumed there must have been an outbreak of infectious disease, most likely influenza. Fuller’s book is dedicated to the estimated 12,000 people killed in that disaster.

The book traces attempts to mitigate the impact of air pollution since that time, with successes including removal of lead from petrol, improvements to engine design and moves away from solid fuel heaters, at least in the developed world.

It is also, though, a call to action. Fuller meticulously details ongoing and new threats to the quality of the air we breathe, arguing we still have a long way to go in addressing problems with particle pollution and the various gas pollutants linked to vehicle exhausts and oil refining.

Meanwhile, the rise of fracking is creating a new source of toxic ground-level ozone and particle pollution.

Although improving air quality remains a challenge in wealthy countries, the real battleground increasingly is in the developing world, particularly the rapidly industrialising nations of Asia.

World Health Organisation figures show more than 90 per cent of the world’s population is exposed to harmful levels of air pollution, leading to millions of premature deaths each year.

A justice issue indeed.

Jane McCredie is a writer with an interest in science and medicine.

Influenza: The Quest to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History

By Jeremy Brown. Text, 272pp, $32.99

The Atlas of Disease

By Sandra Hempel. White Lion Publishing, 224pp, $39.99 (HB)

The Invisible Killer

By Gary Fuller. Melville House, 224pp, $35

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout