World War II child evacuees sent bush recalled in Ann Howard’s book

The stories of Australian children sent inland during the panic of World War II make for fascinating reading.

Of the many hidden histories of World War II, the story of the voluntary evacuation of children in Australia remains one of the most poignant and fascinating. Ann Howard, author of this scrupulously researched and usefully indexed book, was herself a child evacuee from European hostilities. She was removed to what was regarded as the relative safety of the antipodes.

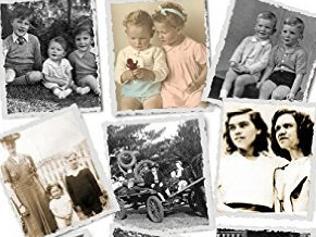

Howard interviewed more than 100 Australians, many of whom provided photographic evidence along with oral histories. She vividly details what poet Les Murray describes in his foreword as “the largest upheaval since white settlement”.

In this sense, the title. A Carefree War. is partly ironic. It wasn’t all soft drinks and skittles. Australia in 1942 was a place of panic. When the seemingly impregnable British fortress of Singapore fell on February 15, we seemed to be undefended. Just four days later came the largest attack on Australia by a foreign nation, the devastating Japanese air raids on Darwin.

Although much information about the bombing of Darwin was censored at the time, this did not apply to the sinking by a Japanese midget submarine, in Sydney Harbour, of HMAS Kuttabul on May 31, 1942, with 21 navy personnel on board. Coupled with scares about Japanese attacks on suburban Sydney, all of this had a devastating impact on civilian morale, especially in coastal Australia.

Gripped by fear and anxiety, many Australian families worried for the safety of their children. As Howard explains, thousands of young children and babies were sent inland to stay with friends and family. For some child evacuees, it was years before they returned home.

Of all the many helpful illustrations in Howard’s compelling history, to this reviewer two stand out. The first is a 1942 photograph of distinguished Australian historian Bev Kingston as an infant, playing outside her family’s air raid shelter at their home in seaside Manly. As it happens, Kingston is Howard’s university mentor and she strongly encouraged her historical research on this topic.

In a chapter titled Keep Calm and Carry On, Kingston wryly recalls their air raid shelter: “Mum wouldn’t go into it, because she said there were spiders. So we put a mattress over the dining room table and sat underneath!”

The second outstanding illustration is a reproduction of a page from TheAustralian Women’s Weekly of January 17, 1941. Headlined “This problem of sending your child away”, it features moving photos of young evacuees.

Howard cites another article from the AWW of December 27, 1941: “In every coastal city in Australia one question has run like a refrain through the news and rumours of war: ‘What are we going to do about the children?’ ”

Indeed ever since Europe had felt the horrors of aerial warfare, it was the plight of children that aroused the most indignation.

When Australia seemed in imminent danger, especially of a possible invasion by the Japanese, hundreds and thousands of parents were preoccupied with the safety of their children.

Many of these parents were women looking after children on their own while their husbands were away from home, fighting. Howard’s interconnected series of stories about Australian child evacuees are often heart-rending but also humorous.

To take just a few stories from Sydney, we have Andrew Kyle, dispatched to a farm at Oberon, NSW, replete with rabbits, and Cecily Atton and her sister, who were sent to stay with their aunts and uncles in Narrabri, NSW.

Anthony Healy remembers that critical year of panic when his dad was in the army and his mother was a working as a cleaner. In mid-1942 he was sent from their home in inner-city Redfern to live in the bush near Orange. Redfern’s Eveleigh Workshops, close to where they lived, were regarded as a likely enemy target.

John Squires recalls that as a 10-year-old, accompanied by his six-year-old brother, he was dispatched by his mother from Paddington to what they regarded as “remote” Muswellbrook — which in fact was less than 120km away. But, Squires explains, “as the Japs didn’t invade, we came back home after three months, in time to survive the shelling, such as it was, of the eastern suburbs later in 1942”. This refers the events of June 8, 1942, when a Japanese submarine shelled Rose Bay, Woollahra and Bellevue Hill, with no loss of life and little property damage.

Ross Fitzgerald is emeritus professor of history and politics at Griffith University.

A Carefree War: The Hidden History of Australian WWII Child Evacuees

By Ann Howard

Big Sky Publishing, 216pp, $24.95