Women’s memoirs: Catherine Anderson, Katherine Boland, Nadine Williams, Robin Dalton

These books explore the rich adventurous lives of four women.

Four women, four rich, adventurous lives. Catherine Anderson has a big, bold story to tell in The End of All Our Exploring. Anderson fleetingly meets Angus McDonald, a noted Australian photojournalist, in McLeod Ganj, high up in the Himalayas near the home of the Dalai Lama and his exiled followers. She explains, “All I wanted was to live and breathe in India.”

Life is hard but stimulating and the scenery spectacular. Eventually she needs to extricate herself from a marriage with an illiterate, abusive ex-monk and leave. “I began to feel uncomfortable in a place that fed hungrily on the misfortune of an entire people — the Tibetans.”

Anderson’s memoir is less self-absorbed, more outward looking, more cerebral, more invested in the world around her, than the other books here. However, hers too encompasses travel, love, illness, loss, death, grief and ways of dealing with the aftermath.

Anderson has been chief of staff to author, Afghanistan expert and British MP and government minister Rory Stewart since 2010 and worked for him remotely during her time with McDonald. She is a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society and has written for The Guardian, Britain’s The Daily Telegraph, The Huffington Post and various travel magazines.

About five years after Anderson returns to England, McDonald contacts her via email. The two fall deeply in love, become engaged, realise they are both “third culture children” — products of peripatetic childhoods. They travel, have a few good months together and work towards combining their lives before McDonald is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

He returns to his family in Sydney for tests and treatment. Anderson joins him. About 100 pages are devoted to McDonald’s gruelling treatment. Anderson sits in on every medical appointment and attends to all of McDonald’s needs. She takes notes, researches diligently and questions everything and everyone.

What is meant by “so-called gold-standard treatments”? “Why subject him to treatment that proclaims itself to be the best option, when it most clearly is not? Why treat if there is no cure? … Why are those who consider rejecting chemotherapy dismissed as eccentric …?”

They switch doctors. They enjoy each other’s company, explore Sydney, read a lot and live as normal a life as possible with much family support.

McDonald goes into partial remission and they chance a trip to Myanmar. In 1994, McDonald retraced the footsteps of Australian explorer George Ernest Morrison from Shanghai to Rangoon (Yangon), a century after Morrison’s journey. Anderson intends to do this trek herself.

Their trip does not end well, though the local people are so kind and generous that in gratitude Anderson sets up the Angus McDonald Trust to deliver grassroots healthcare in Myanmar. She also compiles and edits McDonald’s photos for a book, India’s Disappearing Railways, and curates an exhibition of these photos that is shown in London, Sydney and Melbourne.

Anderson’s writing is vivid and sharp. Of a brightly painted hospital waiting room she writes: “It is depressing precisely because it is trying not to be.” Her book is a bracing, if sad, tour de force.

In Hippy Days Arabian Nights Katherine Boland transforms herself into a successful artist with many adventures following 30 years of hard work and a counterculture life around Bega in NSW. Boland is studying art when she and her partner, John, decide to opt for the utopian life in the 1970s. They clear land and build a mud-brick house on their 40ha plot, leading a subsistence existence while rearing a daughter.

This lifestyle includes much dope smoking, mostly by the men, and domestic violence within the growing community. John has an affair. Boland decides she has had enough and heads back to civilisation, her only sister and her art practice. On the night of her first exhibition in Melbourne, Boland falls headlong into an abusive relationship with the much older, “charismatic, cocaine-sniffing, Croatian architect Vicko”.

Later, aged 52, Boland arrives in Cairo to take up an artist’s residency. She locks eyes across a room with the handsome Egyptian translator, Gamal, exactly half her age and so begins a five-year exciting but predictably star-crossed affair. Eventually it all gets too difficult. Gamal is Muslim, his parents expect to choose his wife, the Arab Spring and its consequences interfere, visa applications to Australia become increasingly complex and values clash. The lovers meet, always in secret in Egypt, briefly elsewhere in resorts, but the “Arabian Nights” turn into bleak days.

The Hippy Days part of this book is more grounded and appealing than the Arabian Nights section, not least because not a great deal has been written about the idealistic self-reliance movement that Boland presents with clear eyes, though with a predilection for descriptors and cliches: “highly amused kookaburras”, “fresh and fragrant day”, “bone-chilling cold”, “like a newly-minted penny”, “grinning at me adoringly, John …” and so on. Boland crowd-funded the printing costs of her book, an increasingly popular method of making a publication viable.

Boland’s book and Nadine Williams’s Farewell My French Love are both compared on their back covers to Elizabeth Gilbert’s hugely successful Eat, Pray, Love. This may or may not commend the books to all readers.

Williams’s book also is hailed as “an accessible take on the enduring market for memoirs tackling grief”. The book offers rather more. Williams’s long career at Adelaide’s The Advertiser largely covered social and women’s issues, and these interests are evident in her memoir. However, it is essentially a frank and insightful account of trying to regain some balance after the death from cancer of her “great French love”, her third husband, Olivier. Williams is disoriented and can hardly recognise herself.

I try and grasp the fact that I had a life before Olivier, an identity as a prominent newspaper woman … Surely I had a gathering of life skills to cope with my adversity? … I am beginning to rue the fact that somewhere in the bliss of my marriage, I lost my sense of independence. I became joined at the hip with Olivier, and my feeling of wholeness included him. Emotional interdependence. I wrote about its dangers before I met him and I never intended it to happen to me. However, such intense togetherness was Olivier’s idea of a French marriage …

Jane, Williams’s lifelong friend, decides a trip to France is the required antidote. While interspersed with recollections about life and travel with Olivier and learning about food and cooking alongside him, the focus is on the restorative power of France.

Williams loves showing off her French, adores Paris, its architecture, charm, cafes, restaurants and boutiques (the book would make a useful travel guide). She is almost obsessed with French female royalty, especially Marie Antoinette and Empress Josephine, and the power they exerted. She muses on the overall status and role of French women and the “lineage of strong French feminists and writers” such as Simone Weil, Segolene Royal, Marguerite Duras and Simone de Beauvoir. “Whatever the reason, gender relations in France are a stratosphere away from Australian society.”

She indulges in fashion and shopping, writing defiantly: “Whether you approve or not, [Galeries] Lafayette is a fabulous women’s world of shopping, of retail therapy in Paris.” Jane disapproves, as she does of Williams’s love of food and of her size, at times petulantly leaving her friend to feast on her own while abstemiously indulging in an apple. There are rather too many vignettes of cafes, hotels, meals, up-and-down moods and tiresome squabbles between the two women.

After Jane’s departure Williams attends a French course and reconnects with some French women acquaintances. She realises her “new life in the company of women … has taken shape in Paris”; that she has gained “delicious freedom” and that she has “scrounged an identity as a widow, living well, alone in Paris [though] the trick will be to take that feeling home on the aircraft”.

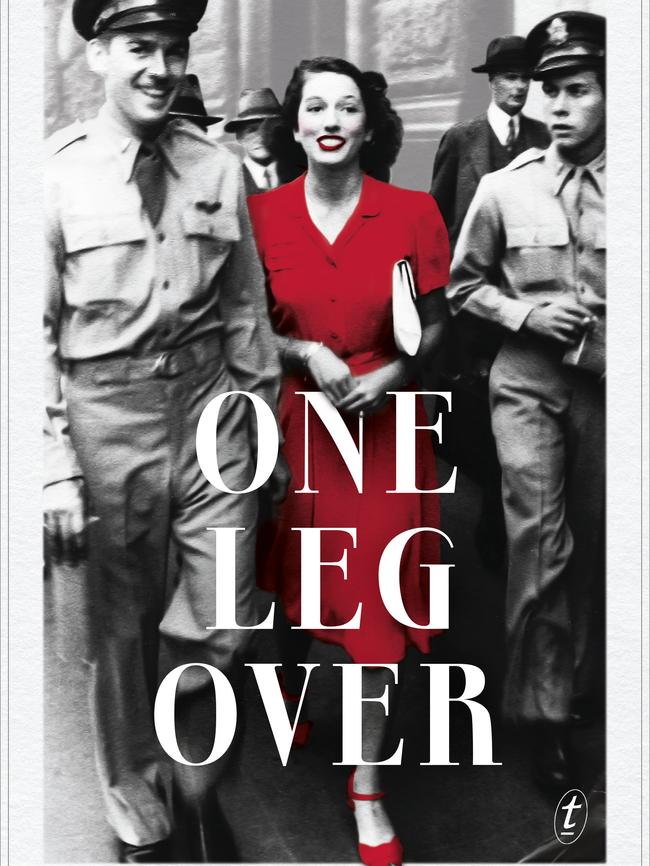

At 96, Robin Dalton is the grande dame here. She is deservedly famous for her work as a literary agent and later as a film producer. Among her stable of authors were Iris Murdoch, Tennessee Williams, Margaret Drabble, Edna O’Brien and Arthur Miller. She produced the film version of Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda. She intends to cover this period in her next memoir (we hope).

At 19, after a scandalous divorce from an older, abusive husband, Dalton became the first female civilian to fly out of Australia after World War II. This was possible only because Daddy knew the head of Qantas. One Leg Over details her hedonistic life among the postwar elite in a London of gloom and rations. Dalton drops dozens of names. Will readers recognise these? How does she remember them? She finds lovers, often more than one at a time. (She laments that these days young people are after sex, not love!)

She frequents exclusive fashion houses, fashionable restaurants, enjoys champagne, cocktails, travel and holidays, and works only sporadically. Funds are provided by family and occasionally by the dubious endeavours of friends. She writes: “Fun and freedom were more enticing than permanence.”

One great love was David, marquess of Milford Haven, a cousin of Prince Philip. As Dalton was divorced they could not marry but spent five years together though she had dalliances when he was elsewhere. There is a charming photo of the two at the Hotel du Reserve at Beaulieu.

Despite severe opposition, as he was a Catholic and she a divorcee, in 1953 Dalton married Emmet Dalton, a doctor, and they had two children. During this time Robin Dalton was offered a kind of ambassadorial cum spying role with Thailand that included exotic trips and much luxury. What this role masked is unclear. Tragically, after only a few years together, Emmet died of a congenital heart condition.

“I discovered that it is possible to grow up suddenly — to burst into adulthood — if you meet a twin soul whose strength beckons you into maturity.” Though Dalton is bereft, help materialises in many guises (“Writer Robert Ruark and his wife Ginny lent me their superb apartment in Park Lane”), including a nanny and sojourns in Italy and Australia.

For 29 years Dalton lived with “successful screenwriter, playwright and novelist” William Fairchild. She married him on their 30th anniversary together. She still lives in London and Biarritz. In an afterword, Dalton writes that in old age contentment is achieved through “the hot water bottle in bed at night and the hot bath in the morning”. “One leg over! — the day’s first and major obstacle is accomplished.” A brilliant title for a brilliant life where “being a woman has been the icing on the cake”.

Agnes Nieuwenhuizen is a reviewer and critic.

The End of All Our Exploring

By Catherine Anderson

Zabriskie Books, 278pp, $28.99

Hippy Days Arabian Nights

By Katherine Boland

Wild Dingo Press, 286pp, $29.95

Farewell My French Love

By Nadine Williams

Harlequin, 266pp, $29.99

One Leg Over

By Robin Dalton

Text Publishing, 197pp, $29.99