William Yang on being seen and heard: ‘There’s huge slabs of gayness through the exhibition’

Photographer William Yang’s work is a moving insight into his life as a gay, Chinese Australian.

Photographer William Yang, 77, is approaching his new survey exhibition with an element of surprise. “I’m pleased they,” he says referring to Queensland Art Gallery, “didn’t baulk at ‘gay’ because there’s huge slabs of gayness through the exhibition. I’m very happy they have embraced gay.”

Any concerns Yang harboured can be traced back to his first solo exhibition, Sydneyphiles, held in Sydney at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1977. It documented the emerging gay scene in the city and featured several male nudes, including an image of two men spooning on the floor at a party. “I knew these two people and they knew me,” Yang said many years later at a talk at the AGNSW. “When I first showed this photo at that exhibition, it never occurred to me to ask them permission if I could show it because I didn’t expect any trouble – and no trouble came.

“The mood at the time was this: people thought throughout history our community has been invisible. This may not be pretty,” he told the audience, pointing at the picture, “but we recognise it and we accept it. We want our stories told.”

Not everyone welcomed the work. Yang was told teachers had warned their students not to see the show.

Even though his work today is held in most state art galleries in the country, Yang says “I think that probably my career has suffered, whether it’s conscious or unconscious. I think that institutions – probably there’s a risk factor that (institutions) might not want to do a big gay exhibition.

“I’ve felt that through my 50-year career, certainly in the beginning. From my very first exhibition, Sydneyphiles, there were murmurs I heard that they didn’t think institutions should be showing gay photos.”

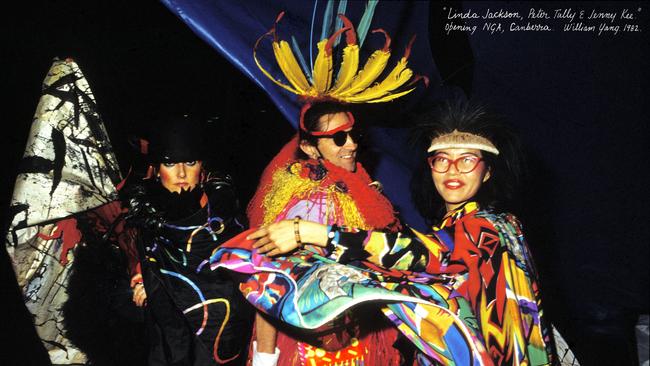

The third-generation Chinese Australian is renowned for his intimate documentary style; with a bright smile and sense of calm he effortlessly puts subjects at ease. When he moved to Sydney from Brisbane in 1969 he couldn’t make ends meet as a playwright so turned his hand to photography, moving about Sydney’s social and cultural scene capturing everyone from writer Patrick White to artist Brett Whiteley, actor Cate Blanchett and fashion duo Linda Jackson and Jenny Kee. Jackson says Yang’s work speaks “really loudly to you, even though he’s not the loudest person in the room”. “There was something about his aura, his way, that could capture those moments. Sometimes it seemed like he wasn’t even taking a photo. It wasn’t like we were all sitting there posing away, we were all free.”

Yang, who came out in the 70s, turned his lens on the LGBTIQ+ subculture, documenting the parties, Mardi Gras parades and the tragic AIDS crisis which devastated the community in the 1980s.

Rosie Hays, curator of William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen, says when it came to selecting the works “it was really important to be able to tell stories from marginalised communities, in particular William thinking out his Chinese identity and stories from the Chinese Australian community and also the LGBTIQ+ community as well.”

By showing Yang’s personal viewpoint of the AIDS crisis alongside the documentation of the Mardi Gras, says Hays, “you have these two beautiful sides of the coin; joy and playfulness and this raucous sense of self-expression alongside very considered personal accounts of community, struggle, pride and identity”.

The gallery also commissioned Yang to create a monologue performance, titled In Search of Home, in which he will tell his story of growing up a gay Chinese Australian in conservative Queensland, in the Atherton Tablelands. It is set to be a poignant piece given that when Yang left Brisbane he had not yet come out as gay, or Chinese, for that matter.

***

“Ching Chong Chinaman, born in a jar, christened in a teapot, ha, ha, ha!” Six-year-old Yang had no idea what this meant when a child at school chanted it to him, although he could tell from the wretch’s expression it was an insult.

“So I went home to my mother and I said to her, ‘Mum, I’m not Chinese, am I?’ And she looked at me very sternly. And she said, ‘Yes, you are’. And her tone was hard. And I knew in that moment, that being Chinese was like a terrible curse. And I could not rely on my mother for help.”

Yang recalls this formative memory, one he has recounted many times, at the Chinese Garden of Friendship in Sydney’s Darling Harbour, an inner-city oasis designed around a large tranquil pond in which koi jostle at the surface. It was here, on the bridge over the water, that people would gather in the 90s to watch Yang and his friends from the Asian Lesbian and Gay Pride group perform in one of the pavilions for the Chinese New Year Parties that were held as part of Mardi Gras. A photo of two Asian men wearing coats of mail and a woman in bunny ears – you can see the reflection of Yang’s camera in her metallic brassiere – was taken before one of these performances in 1999 for the Year of the Rabbit.

“When you come out, the very act of coming out is a political act, I think, because you’re visible,” says Yang against the bubble of a water feature in the background.

“I felt that being a gay person, my sexuality had been suppressed. And then when I ‘came out’ as Chinese, I felt that my ethnicity had been suppressed. And so I embraced my Chinese heritage. And I did works about it.”

One of those works was Sadness, a 1990 photographic series that was later made into a film by Tony Ayres. By this time Yang had taken to showing his photos as slide shows to which he would talk, and writing little stories on them in cursive. Ayres took Yang’s presentation and layered upon it footage of the photographer travelling back to his childhood home to investigate his roots. It’s a story of grief and intergenerational trauma. It’s a story of murder.

***

Yang’s aunt Bessie (his mother’s sister) was only 16 when she married William Fang Nguyen, a rich Chinese landholder. Bessie’s whole family left the Northern Territory to live under Fang Nguyen’s roof “Chinese style” in Mourilyan, North Queensland. Nguyen, who some said was arrogant, didn’t get along with one of his employees, a white Russian by the name of Peter Danelchenko and, during an argument in 1922, the Russian shot him.

“The outrage was that at a trial the jury found that the white Russian was not guilty because he had only killed a Chinaman. That was the sentiment,” Yang says. “I feel that the legacy of that story came down to me and my mother didn’t want to have anything to do with anything that was Chinese. She wanted us to be more Australian.”

Seventy years after the murder, Yang travelled up to North Queensland to visit the site of the murder and piece together what had happened. At Innisfail courthouse he found a police sketch of the murder scene, the outline of his uncle’s body on the floorplan, and the documents his uncle was holding when he was shot. Yang wrote beneath his photograph of the papers: Oh my god! His blood was still on the documents, a kind of brown, crystallized stain.

The process of reclaiming his Chinese identity also led him to visit his mother’s hometown in the city of Toisan but he didn’t find the feeling he was searching for because the place was so remote and his family connections had been lost. It was actually at the steelworks in Baotou in Mongolia, where he travelled with a photographer friend, that he had his most identifying moment.

Yang was invited to sign the visitor book in the common room for the VIPs. While others scribbled slogans, he treated the book like a diary and wrote a meaningful passage about how good it was to be back in China. A woman there read the entry and told him: “It’s true. The blood of China runs in your veins.”

Looking back on that moment, Yang smiles. “People talk about going back to China and finding that they’re Chinese. Amy Tan talks about it. She became Chinese the minute she set foot in China. It didn’t happen like that to me, but in that workers’ common room that was like my moment.”

The most moving series in the exhibition features his friend Allan, a man Yang dated in 1980. Allan agreed to let Yang photograph him as his body succumbed to AIDS and as writer Benjamin Law writes in the catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition, “I defy you not to struggle with tears”.

There are also strong reminders of what the community was dealing with in Yang’s photographs of Mardi Gras such as a 1993 photo of two men with the words scrawled on their torsos: ACTION = LIFE, SILENCE = DEATH. “Mardi Gras was very important in the era of AIDS, so people could express themselves and it was like a communal gathering in solidarity,” Yang says. “That’s probably one of its chief functions back then, solidarity of the community.”

The parade today, of course, is a more commercial affair with everyone from banks to mobile phone companies taking part.

“It’ll never be like it was in the 80s, the golden era,” says Yang, although it’s still very vibrant and “has a lot of young people and a lot of energy”.

We happen to visit the garden on the Monday after the parade weekend. Back in the 80s Yang would stay out all night taking pictures at the party and wouldn’t be back home in Bondi until after dawn. This year he watched the parade on television because he was busy preparing for his survey show. Plus, if he had attended the event he’d have a problem on his hands.

“Suddenly I’d have a huge volume of photographs and then I’d have to edit them and post them,” he says, referring to his Facebook page. “I can’t help myself.”

William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen is showing at Queensland Art Gallery from March 27 until August 22. Yang will perform In Search of Home at GOMA, Brisbane, at 11am on March 27.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout