Wilde ballet may challenge patrons as it breaks new ground

The Australian Ballet is breaking new ground with Oscar, a ballet about the flamboyant life and romantic loves of Oscar Wilde.

You can now listen to The Australian's articles. Give us your feedback.

In January 2022, David Hallberg flew to New York, one of the first trips he had made after becoming artistic director of the Australian Ballet during the pandemic the year before. The New York native had a laundry list of people to catch up with but top of that list was good friend and colleague Christopher Wheeldon. The pair had known each other for two decades, both working in the international dance scene and moving in similar social circles. Significantly, Wheeldon was the last person to choreograph a work on Hallberg, a former international superstar of the ballet world.

That work, The Two of Us (2020), to the music of Joni Mitchell, was filmed but never performed live, thanks to the pandemic; and Hallberg had unfinished business. But it was no longer about him. Instead, Hallberg was inviting Wheeldon to create a new narrative ballet on the dancers of the AB, his first commission in the new role. Wheeldon, one of the most sought-after choreographers in the classical ballet world, was only too happy to oblige.

That January afternoon the pair sat together in Wheeldon’s Upper West Side apartment and talked through various ideas and concepts but found themselves continually circling back to one: the first full-length classical ballet to explore the life and work of literary sensation Oscar Wilde.

Of course, these things never happen overnight and the British-born Wheeldon first had the small matter of a world premiere to attend to: his production MJ the Musical about the life and music of Michael Jackson. It opened on Broadway the following month, going on to tour America and the West End (it lands in Australia in February), earning four Tony Awards including best choreography. Hallberg was prepared to wait.

“Chris and I have been friends and colleagues for the better part of 20 years; the history is long and winding and he happens to be one of, if not the greatest storyteller in the ballet world, both choreographically and narratively,” Hallberg says. “I basically said to him it’s an exciting moment for the Australian Ballet, I’d just come in, I really want to tell a bold story, whatever that is, are you interested?”

AB audiences are no stranger to Wheeldon’s work, having enjoyed return seasons of his joyous, madcap production Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the sublime After the Rain and more recently the Broadway musical An American in Paris that Wheeldon directed and choreographed, another Tony Award-winner that showcased various dancers from the AB in the cast. But never has the company been treated to a Wheeldon work created specifically for them.

Both Hallberg and Wheeldon agreed the production had to be Oscar Wilde.

“Oscar’s stories are full of colour, full of beauty, full of imagination. That’s what you want in any narrative ballet. He was a man of complete wit and intellect, so there’s that side of who he was as an artist, which is great nourishment for balletic storytelling,” says Hallberg. “But on the other hand, Oscar lived a life that was really colourful, to say the least.”

Speaking to Review during his third trip to Australia to work with the dancers, Wheeldon recalls those early conversations in New York, particularly his interest in putting a gay love story on stage.

“We both bemoaned the fact there were very, very few if any full-length story ballets that had queer themes or centred around queer love stories. Of course, Oscar’s life was full of turmoil and did not end well at all, but there were moments of great beauty and poetry and devotion and romanticism and true love. All of which are lived experiences for me and for David,” Wheeldon says.

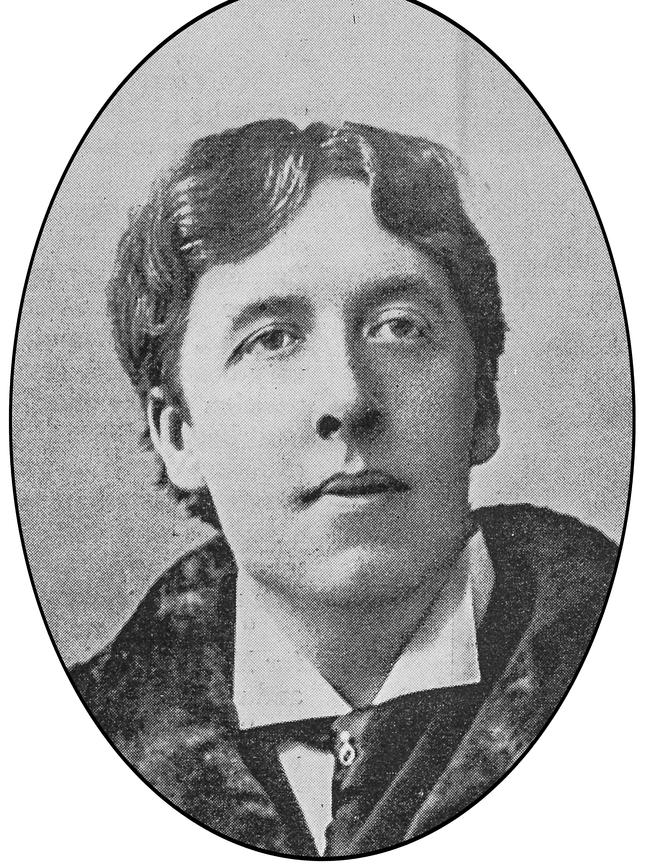

Today, more than 120 years after his death aged 46, Wilde is still celebrated as one of the world’s greatest satirists and storytellers. Born in Dublin in 1854, he was awarded scholarships to attend first Trinity College, Dublin and later Magdalen College, Oxford, where he became well regarded as a classical scholar, humourist and award-wining poet. He would go on to become outrageously, unapologetically flamboyant in both dress and behaviour, quickly catching the eye of London’s literary and societal circles. His dark fairytales and sharply observed, often bitingly funny social satires Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891, his only novel) earnt him a reputation as a gifted humourist, a reputation that endures to this day.

Just as his fame was at its peak however, Wilde – a married father of two – was convicted and sent to prison for homosexuality, a criminal offence at the time. He was released two years later in 1897 and spent his final three years in Paris, where he died suddenly of acute meningitis.

In shaping the story for Oscar, Wheeldon wanted to bring to life this great, complex character through Wilde’s own words, weaving the story of his life throughout. He began drafting a synopsis with friend and TV writer Alexander Wise, before continuing with his Alice and The Winter’s Tale collaborator, composer Joby Talbot. The pair hid themselves away in a hotel in the Italian Tyrol, writing madly, before Wheeldon sent Talbot off to begin composing the score for Oscar.

“Joby and I spent a wonderful three-day period staring at the mountains playing with the concept for the work,” Wheeldon says. “There’s so much drama, which can be great fun to choreograph, so much poetry and beauty that can be distilled to an essence for this work. Of course, there’s the love story, not just with the men in his life but with his wife and children, and how they were affected by Oscar’s relationships.”

Wheeldon firmly believes any biographical story needs something for the audience to hold on to, particularly with the life of Wilde, which audiences may not be familiar with, despite knowing and loving his published work.

“Anything biographical can present a whole lot of problems – biopics, bio-musicals – and Oscar’s work is so multi-faceted and full of paradox and complexity and light and dark and effervescence and wit and then the depravity. There are so many ways you could go that I felt like I needed anchors.”

This production, then, is anchored around the rise and fall of Wilde, woven around the portrayal of two of his most cherished works: the tragic fairytale The Nightingale and the Rose, and the haunting and still hauntingly relevant The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Wheeldon has had a long and storied career in classical ballet and musicals, initially as a dancer with The Royal Ballet from 1991 and later New York City Ballet. In 2001, he was named that company’s first resident choreographer, and he would go on to create productions for most of the major international ballet companies, including the Bolshoi Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet and Hamburg Ballet. Today he is artistic associate at the Royal Ballet and continues to create and stage works around the world.

But never in all his decades working with classical ballet has he seen a love story where the prince falls in love with a prince, not the princess. He and Hallberg believe it’s time, believe audiences are sophisticated enough to enjoy a love story as diverse and non-conformist as Wilde’s.

“In many other artforms the handling of (queer) themes has been much more progressive than it has in ballet. Just look at Netflix,” says Wheeldon. “The younger generation are far more accepting, queer culture is becoming more normalised in many ways but unfortunately it’s not enough and there are still battles to be fought. It is a part of life, as queer people we are born as queer people and our stories deserve to be represented in art in the same way that hetero stories are represented. So I think it’s time. We certainly don’t mean to offend in any way. I think it’s very much about how you handle these things, how they’re expressed theatrically, where the focus lies.”

When programming new works, and indeed a season in general, Hallberg is conscious of audience tastes and appetite for the new, and he too believes audiences are ready.

“What I can attribute it to (the lack of ballets depicting queer love stories) is a lack of courage, and fear. Fear of consequence, fear of alienation of our audience, fear of risk, and it’s sad to say this is even considered a risk,” Hallberg says. “I was never given the opportunity to fall in love with a man on stage. I certainly have fallen in love with men in my personal life (but) it was always this assumption from me as a gay man to just do the work – fall in love with Juliet, fall in love with Princess Aurora, fall in love with a swan who just happens to be a woman – and not say ‘this doesn’t feel natural for me’.”

Wheeldon was cautious when approaching some of the love scenes between Wilde and his lovers, conscious of not wanting the movement to leave any of the male dancers feeling uncomfortable.

“Even (though) they’re really quite a progressive company, I wanted to make sure I set the project up really well for them. Many of the dancers are straight men and I wanted them to know we were obviously going to be dealing with some very intimate moments in the story and if ever I was asking somebody to do something they didn’t want to do we’d just talk about it, and it wouldn’t mean they wouldn’t get to dance the role or be pushed out of the work. It was very much about open communication. And I have to say, I’ve had zero problems.”

The role will be shared between principal artist Callum Linnane and senior artist Jarryd Madden. In a moving interview on the company’s website, Madden reveals how humbled he feels performing the role of Wilde. “A lot of our closest friends are queer and so for the better part of their careers they’ve always had to fall in love with a gender they weren’t personally aligned to, so the fact that we get to live in their shoes for once in our professional career and experience what they’ve had to live through forever, that’s a really beautiful moment and I’m excited to do that in support of them,” says Madden, who is married to fellow principal Amy Harris. “It’s a kickass story anyway, so it’s exciting to tell this narrative.”

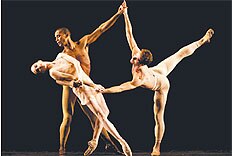

Wheeldon says it is also refreshing to create more complex parts for many of the male dancers, whose role traditionally is to support the ballerina and enable her star to shine.

“Another thing that’s quite important to me, and I think the men in the company appreciate this whether they’re gay or straight, is this is a ballet that focuses on male dancing and male partnerships. So much of ballet has historically focused on the ballerina, with the male dancer the cavalier behind her, so it’s nice to have a balance with the men for once.”

If any audience member should take umbrage, they merely need wait for the AB’s Christmas production, The Nutcracker, for more traditional fare.

Wheeldon has relished his first time working so closely with the AB, and is appreciative of their down-to-earth approach to work, and life.

“There is such an openness about Australians in general, I’ve always loved that about coming here,” he says.

“The dancers have been absolutely on board from day one. Part of that comes from the excitement of being involved in a new creation, especially one of this scale, but also it is the nature of the way the company works – they’re workers, and it’s just a delight.”

Unusually for Wheeldon, he finds himself approaching Oscar’s opening night with mixed feelings.

“I’ve had the most wonderful time. Usually at this point it’s full steam ahead and I’m thinking ‘Oh god, we’ve just got to get to opening night’. But there’s a part of me that’s dreading opening night because it means I’ll be taking off a couple of days later. You do forge very strong creative relationships with the dancers when you’re at this scale for so many weeks, and I love them, I really do.”

Oscarwill be performed at the Regent Theatre, Melbourne September 13-24 and the Sydney Opera House November 8-23. A ticketed livestream will be broadcast on November 19.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout