Why Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s story is being retold

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s family is seeking to entrench the Indigenous superstar’s legacy with a new posthumous album.

When he was at the height of his fame and touring Europe, Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu liked to phone home. With an expression that lies somewhere between a grin and a grimace, Gurrumul’s close friend and long-time collaborator, Michael Hohnen, remembers the “pretty massive” mobile phone bills the late singer would rack up.

No matter how fancy his hotel, or how cosmopolitan the city he was visiting, the Gumatj man, who was born blind and grew up on Elcho Island (Galiwin’ku) off the Arnhem Land coast, liked to fall asleep listening to a soundtrack of ceremonies and funerals occurring in real time back home.

Hohnen, the co-founder of Skinnyfish Music, recalls how “that was before FaceTime or any of that in France. It was a nightmare trying to get a SIM that didn’t cost two dollars or three dollars a minute … He’d go to sleep with it (his phone) on, because there was always ceremony in the background. Funerals going for days, and he just listened to the funerals and the singing of hundreds of different songs.

“So he would just have that phone on in his hotel room the whole time. And in France, if you think that’s $3 a minute – it was recoupable from our touring costs but it was pretty massive. It’s funny now, looking back on it.’’

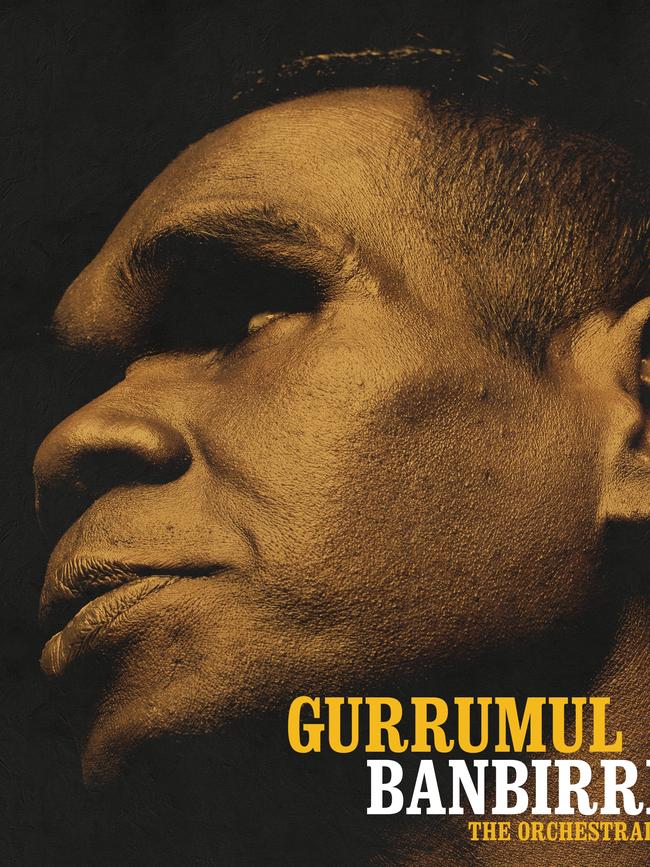

Hohnen is speaking to Review about the unlikely, self-taught superstar who died in 2017, aged just 46, at an industry preview of Banbirrngu – The Orchestral Sessions, a recently released posthumous album of Gurrumul’s music. As its title suggests, Banbirrngu features orchestral re-workings of some of the singer’s most loved songs, including Bapa, an achingly tender tribute to his father, and the six-minute Wiyathul, a hauntingly ethereal song about longing for place.

Visiting Sydney’s Forbes Street Studios on traffic-choked William Street with Hohnen is Don Wininba Ganambarr, a Yolngu cultural leader from Elcho Island who is married to Gurrumul’s sister, Jennifer Djapu Yunupingu. Ganambarr spent several days (at a cost of $5000) making his way from his remote island home to the NSW capital for the industry launch and this interview.

Gurrumul’s brother-in-law is dressed in a just-purchased University of California hoodie because he finds Sydney’s warm spring weather chilly. He carries responsibility for cultural and family matters on the maternal side of Gurrumul’s family and he co-directed the posthumous touring stage show, Bunggul, in which dancers, songmen and a didgeridoo player from Elcho Island performed to a recital of the singer’s Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow) album. The critically celebrated production toured to Sydney, Perth, Adelaide and Melbourne from 2020 to 2023.

Although it is often taboo to use the names of deceased Indigenous people, Ganambarr says that during his lifetime, Gurrumul “was always concentrating on Yolngu music, to bring that music to wider Australia. That is why, when he died, the family said, ‘We may as well use his name’.’’

The elder says it is not fully appreciated that Gurrumul’s songs are not merely about walking along a beach or having the wind in your hair. “Some of the songs go back thousands of years,’’ he says. Through Banbirrngu: The Orchestral Sessions, “the music lives on. The family have been asking for this.’’

Asked to share a funny memory about his brother-in-law, Ganambarr tells of the time the singer asked for some fresh-caught fish. His features softening into a wry grin, the cultural leader says: “The funniest moment I had with Gurrumul, I was eating a fish, a Trevally. Gurrumul said, ‘Can you leave me some fish?’ So I gave him some fish. And he said, ‘Can you take all the bones out?’ And I said, ‘Hey Gurrumul, can you feel the bones then take the bones out, then eat?’ ”

Gurrumul insisted all the bones be removed for him, and recounting this anecdote, Ganambarr cracks up. “He even used to say ‘You’re not killing me!’ ”

Banbirrngu is produced by Hohnen who, for years, played double bass onstage alongside the singer. The album is arranged by Finnish-Australian composer Erkki Veltheim, who also toured with Gurrumul, who famously played his guitar upside down.

The album was recorded by the Prague Metropolitan Orchestra under the baton of conductor Jan Chalupecky. Released by Decca, it comprises 10 songs ranging from the titular track, a meditation on how life and the environment intersect, to Baru (Crocodile), which draws parallels between the fearsome reptile returning to her nest and the Gumatj people returning to their traditions.

Ganambarr says the album’s new version of Amazing Grace, backed by lush orchestration, speaks to how Gurrumul attended church as a little boy, where he learned harmonies. The elder says: “He used to sing in church every Sunday. He used to go with his parents to the church.’’

According to Hohnen, Gurrumul made his The Gospel Album (2015) as “a dedication, but also a thank you to all of those older women who brought him up. The men taught him the traditional manikay, serious Gumatj songs, and a lot of his aunties, his mother, who would always ring us on tour, all of those people gave him the gospel side of the world.’’

It is hoped the new album will bring Gurrumul’s music to a wider audience, especially Gen Z music fans who might not be familiar with that peerless high tenor voice, which seems at once fragile and assured, and is so filled with longing and tenderness it can make hard men cry.

Although Gurrumul’s solo career (2008-2017) was brief, Rolling Stone called him “Australia’s most important voice”. Sean Warner, president and CEO of Warner Music, which is releasing the new album, said: “I don’t think he would have realised the cultural significance his music has had.’’

Warner says Gurrumul’s songs, sung mostly in his Yolngu languages, connected Australians and fans around the world “to the original cultures of this land’’ in a new way.

Posthumous albums are sometimes criticised as inorganic marketing indulgences; empty money-making exercises dreamt up by recording companies or artists’ estates. But Hohnen says that, almost eight years on since Gurrumul’s death, his significance as a standard bearer of Yolngu culture is underappreciated.

He says: “Many of Gurrumul’s family see his contributions to the world as something representative of them. It’s often been communicated to us that they did not want to see Gurrumul’s name lost or forgotten.

“Years ago, Gurrumul and I were working on a whole range of different options before he became too sick to complete them. These included different versions of old songs and some songs that had never really been noticed. His voice and repertoire are still so powerful, and now they can be rediscovered in a fresh light.’’

Pointing out that the new album “offers just a glimpse of the new material we have to present’’, Hohnen suggests there are more posthumous albums to come.

In the late 1980s and 1990s Gurrumul started his musical career with Yothu Yindi and the Saltwater Band, rarely performing upfront. Hohnen could see the potential of his extraordinary voice, yet when he first suggested that Gurrumul record a solo album, the singer resisted.

Finally, Gurrumul’s self-titled debut album, Gurrumul, was released in 2008 to a chorus of international praise. It went triple platinum and sold 500,000 copies.

As the Aria-award winner brought Yolngu songlines to mainstream audiences, he performed for Pope John Paul II, Barack Obama and Queen Elizabeth II and counted Elton John, Sting, Quincy Jones and Stevie Wonder among his fans. Interestingly, Hohnen says this traditional man may have been brought up in a remote community, but he was unsurprised by his global success: “Deep down, he knew he had special talents.’’

Hohnen recalls that Gurrumul used to dissolve into laughter when radio and TV announcers overseas struggled to pronounce his name. Sometimes, when doing media interviews, including live TV and radio interviews, he simply maintained an enigmatic silence, rather than answer questions, so Hohnen was often obliged to act as his spokesman.

The singer shared stages with other leading Australian performers including Missy Higgins and Paul Kelly. The latter recorded a version of Amazing Grace with him in 2015 and writes in a note to coincide with Banbirrngu’s release: “Whenever he sang, you could feel a change come over the audience, a descending hush of rapt attention’’.

Gurrumul recorded four albums during his solo career, and his experimental posthumous album Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow) reached number one on the ARIA charts in 2018.

It’s often said that his astonishingly pure voice stops people in their tracks. For Ganambarr, listening to the latest album – the third posthumous work following Djarimirri and 2021’s The Gurrumul Story – was highly emotional. “I know exactly what words he is using to sing Baru (Crocodile),’’ he says. “When I hear it, I can feel it. Hear him touch my heart. I can think back where the country is from, where he is singing to. It touches people like me.’’

Asked why Banbirrngu was recorded with the Prague Metropolitan Orchestra, Hohnen says: “Practically, it was really quite easy to do. It was probably mega expensive to try to do it with some big orchestra here. But also, Erkki is a European. His roots are in European culture, and I think this gives it a different, European focus. You listen to old movies where they have a classic sort of sound … If you listen to the orchestrations they do sound like an older-style orchestra, which I quite liked.’’

Gurrumul’s death in his mid-40s was cruelly premature. Do his friends and family still miss him? Ganambarr says simply “we (the family) do; I do’’, while Hohnen admits to a sense of not knowing what you’ve got until it’s gone. “It’s hard being so close to someone, and when they’re blind, you’re actually responsible for them,’’ he says. “He loved relying on other people rather than being autonomous. So you’ve got that connection and that responsibility, and then suddenly it’s gone. And this is really hard to describe.

“You know when, say, your parents are really annoying because they’re always making you do things you don’t really want to do, and then you lose them, and you go, ‘I really miss that’. It was the same with him.’’

The singer suffered from hepatitis B and kidney and liver disease for many years. Hohnen recalls that “when he started to get really sick – he got sick over 10 years – I missed his full strength and energy and spirit. Even though it created a lot of work, the work was rewarding. And it’s that old-fashioned thing about if you work hard, it’s really rewarding. So I suppose that element I really miss as well.’’

Gurrumul died in a Darwin hospital but spent his final days living at a so-called “long grassers” camp in the city that was filled with itinerant drinkers. Hohnen says while “there are a lot of people with serious addiction (in the Northern Territory), he wasn’t anything like that. Because he (usually) lived remote, alcohol wasn’t really a problem, unless you come into town. It’s not like a 24-hour sort of prevalence.”

The musician and producer says Gurrumul smoked and had a “terrible diet” but that it was hepatitis B, which he acquired as a teenager, that meant his health was “so deeply compromised’’. He adds: “The health system in the bush leaves a lot to be desired and a lot more can be done to resource remote communities with the same sort of health system that we have in the cities.’’

While in Darwin, towards the end of his life, Gurrumul missed some of his dialysis appointments – he reportedly hated having such treatment. Hohnen observes that locating such essential services in larger remote communities “is something that in the future might help a lot of people’’.

Both Ganambarr and Hohnen agree that when producing the new album, a careful balance needed to be struck between preserving the singularity of Gurrumul’s voice with the bigger, lusher sound of the Prague orchestra. The elder says: “I like the balance, how he used to sing and every time I was listening I was really touched by the sound of the orchestra.’’

Hohnen, who is now working with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra on a project to record Indigenous songs from that state, says: “I think the glistening, glossy, sensitive quality is what we’re trying to achieve. And that’s what I feel we’ve got. It feels like it adds this layer of depth and quality to what was there before. I love what was there before, but … we’re always thinking about how we can present something in a different way.’’

Interestingly, Hohnen admits he wasn’t completely happy with Gurrumul’s third album, a recording of a concert with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra that later became the ARIA Award-winning album, Gurrumul: His Life and Music (2013). Some fans apparently thought the orchestra at times overwhelmed Gurrumul’s voice. “We were just trying it live then,’’ says Hohnen. “But really, it wasn’t an amazing representation. I think here (the latest album) is a much more, for me, quality representation of the intent of what we started back then.’’

While the producer tried to convince Gurrumul that people loved his “stripped back” concerts that emphasised his voice, the singer loved having big backing bands. “He was always saying, ‘I want to have more people behind me.’ When we used to go out in the early days it was double bass, guitar and him,” Hohnen says.

“He used to say ‘Can I have more backing behind me?’ I’ve seen a couple of videos of him playing with an orchestra and you see this sly smile, as if, you know, ‘I’ve got 60 people behind me and I’m kind of in control’. I loved watching that, but I was trying to say all the time, ‘stripped back is what people love, right?’ But he was always going, ‘No, no. I need more. I need more backing behind me, drums or whatever’.’’

So, from beyond the grave, has Gurrumul won that battle of wills, with this new orchestral album? Hohnen laughs. “Yes, in one way,” he says.

Gurrumul Banbirrngu: The Orchestral Sessions is out now