The hushed communion of a cloister of collared vicars hums through the walls of a former British school for infants. And if you listen closely you can hear the faint, but unmistakable, echo of ping pong balls ricocheting through this old building’s bones. Outside, a tempest named Storm Debi is raging. Rain and winds up to 100km/h are whipping the picturesque English seaside town of Brighton into a sort of dark and deluged dystopia, its famous pier sodden and bereft of tourists. The neon’s on but no one’s at home.

Yet here, nearby in the working studio of internationally renowned British artist David Shrigley, things are just as one might imagine they would be: calm, quiet, and just a little bit weird.

“Accept the pissing rain,” screams an apt, unfinished, painting on an easel in the corner of the space, which the artist shares with the Catholic Church and a table tennis community group. Towering boxes of filed items variously labelled “Pokey things” and “To be reminded of my failures” climb the walls of the studio. A small Duchamp-style mini-urinal is perched on a window ledge, and a tiny scrawl-on-paper nearby urges: “Try to be a good person”.

I carefully dodge a wayward tennis ball on the floor, and before I know it I’m perched on a stool, with the sleeve of my T-shirt pulled up to my shoulder.

Shrigley sits opposite with a felt-tip pen hovering, without a hint of tremor, above my tricep. “What are we doing, David?” asks his gallery assistant Hayley. Shrigley carefully presses pen to flesh. “We are doing a tattoo,” he says. “Tim’s tattoo.”

Over Shrigley’s shoulder, a wild capitalised scribble reads: “The artwork. It never turns out the way you want.” I flinch.

He pauses and brings his pale blue eyes briefly to mine.

“Don’t move.”

-

Until 2016, Shrigley says, he had never been certain of his place in the art world. It’s a startling statement for an internationally acclaimed artist who just three years earlier had been nominated for Britain’s most prestigious art award, The Turner Prize, and whose work is held in the collections of some of the world’s best known art institutions (MoMA, The Tate, and Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art among them). That’s not to mention his huge social media following; he has more than a million devotees on Instagram alone.

But the 55-year-old, best known for his satirically dark and whimsically sardonic illustrations – as well as for sculptures, paintings and books – had always felt like something of an outsider in the art establishment. Then he got a commission that changed everything: The Fourth Plinth project. The British arts initiative places for two years contemporary sculpture on an unused plinth in Trafalgar Square. Shrigley entered his design on whim. He thought they’d never choose it. They did. And on September 29, 2016, then London mayor Sadiq Khan unveiled what is now arguably Shrigley’s most famous work: Really Good.

When the 7m-high sleek black hand cast in bronze giving an exaggerated thumbs-up was erected in the heart of London, Shrigley felt he finally had broken through some sort of fourth wall.

“At the time, I kind of thought, ‘Well, I’m not really the kind of artist that gets these kinds of commissions – it seemed like a very much insider type thing. My impression was I was never quite included in the serious stuff.”

But Shrigley’s work was taken more seriously than he imagined. Really Good was a sensation in Britain, whose citizens just months earlier had voted yes to Brexit. Khan seized on the opportunity to interpret the work as a symbol of optimism against the backdrop of a soon-to-be post-Brexit Britain, its exaggerated thumb – mimicking in its own way the neighbouring Nelson’s Column – reaching to the sky as some sort of sanguine beacon. Others interpreted it as a sardonic nod to Britain’s decision to leave the EU.

So, David Shrigley, which was it: symbol of hope or grand pisstake?

Shrigley sips his coffee. “Well, originally I was talking about it in the context of Brexit,” he says. “I said also at the time as public artwork, it will have some self-fulfilling prophecy where it will make the world better. It was obviously a deeply ironic statement then.

“What I find really interesting is now I realise that this work is a positive intervention. It’s an artwork that’s both sarcastic and sincere, simultaneously.”

Shrigley, who in 2019 was awarded an OBE, says the work is open to interpretation. Apart from anything else, he proffers, far worse things than Brexit have happened in the time since it was created: wars in Gaza and Ukraine, climate change, and the small matter of a years-long global pandemic.

It’s fitting then, perhaps, that the work should have been shipped out from England and plonked in the centre of Melbourne, home of the world’s longest lockdown. Really Good now stands in the forecourt of the National Gallery of Victoria, marking the opening this weekend of the institution’s Triennial exhibition. The third iteration of director Tony Elwood’s three-yearly art extravaganza will be the largest on record. Running until April 27, the show’s line-up of artists includes Yoko Ono, Shelia Hicks, Tracey Emin, Maurizio Cattelan, Thomas J Price and Flora Yukhnovich, among others.

The NGV has shown Shrigley’s work before. In 2014, it held a retrospective of the artist’s illustrations, and Ellwood has praised Shrigley’s works “for their humour and ability to convey the most complex as well as trivial moments of human experience”.

How, then, does Shrigley interpret his own oeuvre?

“My work is really just a statement made by an individual,” he says. “It’s not a demonstration of objective drawing skills. It’s a demonstration of angst.”

Shrigley’s art, especially his works on paper, is not, by any means, technical drawing. His rudimentary illustrations of simple ideas – people or animals, in the main – are more often than not accompanied by a message, always typeset in the same slightly off-skew schoolboy capitalised lettering. The message can be poignant or emotionless; humorous or sad. See the figure in red painted awkwardly – claustrophobically – into a blue box, inside which are the words “Happy place”. A rooster crows the word “F..k”. A set of crayons beneath text: “I would like to write on your walls with my crayons. Is that okay?” Rain from a cloud falls into the eye of an anguished man looking skyward: “It won’t be like this forever.”

Shrigley amuses and engages like few artists. As English art critic Adrian Searle notes: “His work is very wrong and very bad in all sorts of ways. It is also ubiquitous and compelling. There are lots of artists who, furrowing their brows and trying to convince us of their seriousness, aren’t half as profound or compelling.”

So where does it all come from and why does it so resonate?

“The short answer is I don’t know,” Shrigley says. “I’m an introverted person, and that is borne out in my work, and I think perhaps people find that accessible. But I don’t look back. I am only interested in what I’m doing today, or better still, tomorrow. I am like a slug that leaves a trail of slime behind.”

Many of his fans see his art as therapy. There are multiple fan groups online dedicated to the emotional depths of his output.

And then there is the other more intriguing cult — one Shrigley says he understands even less than the resonance of his work with the tens of thousands of fans who engage with his art daily on Instagram and those who pay upwards of $200,000 for his work.

It’s those who seek a permanent Shrigley original – the tattoo brigade. Shrigley’s fans, according to his team’s own research, are young people – mostly women between 25 and 35. At book signings and events, fans approach him and ask for him to draw on their bodies, which they then have tattooed. So prevalent is the cult the artist now carries with him a sterile pen.

There is suffering for one’s art. But suffering for someone else’s? Shrigley has said the idea “freaks me out”. But his own website features a gallery of some of the results. There’s the word “TOE” written vertically down someone’s foot-bound digit; an arm with the word “leg” inside it; a man standing on a table urinating on to the floor; a Yorick skull so roughly drawn a child might have done it.

“I don’t get it,” Shrigley says, laughing softly. “I have no tattoos, and I do find it a bit of a weird thing. But then it’s interesting. There’s the idea you’re supposed to spend a lot of time making the graphic for a tattoo – people put a lot of thought into it. But if you draw it straight on, it’s interesting. It’s public art, I suppose.”

-

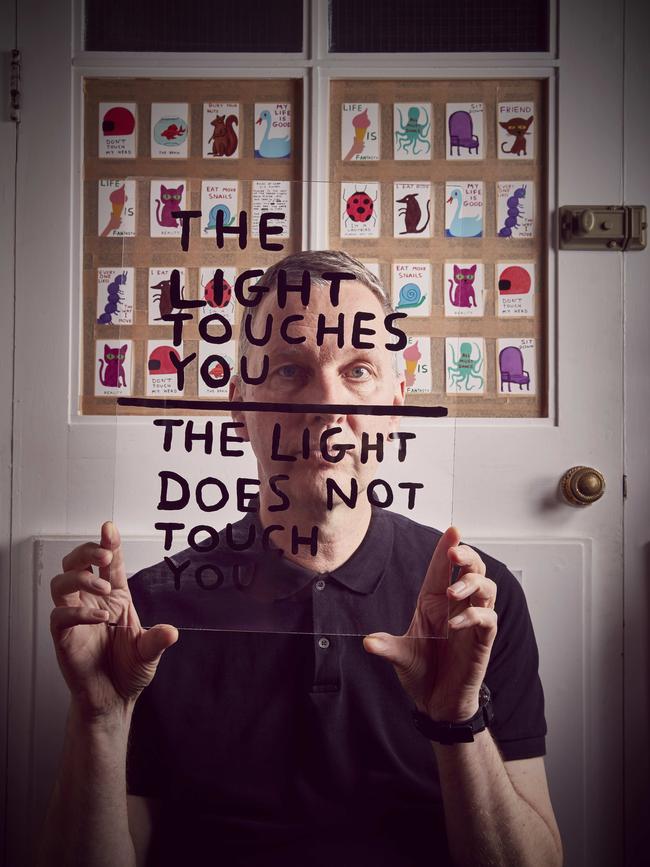

Shrigley is drawing a glass of water, about the size of a postage stamp, on my arm with that special sterile pen. It’s all for a laugh, really. I am interested, I tell him, to know what it is that compels his fans to have his designs drawn on them. The rain raps incessantly on a window across which are painted the words “The light touches you; The light doesn’t touch you”. There is a curious intimacy, a silent performative element – to the action. As Shrigley focuses on his freckled canvas, Hayley looks on suspiciously. “You’re going to get this tattooed, aren’t you?” she prods. “Why are you so nervous? I can take you right now if you want. The tattooists love when someone comes in with one of David’s works.” Why am I so nervous? I have no intention of having this made permanent. Shrigley passes me the glass of water.

-

David Shrigley is tall – 197cm – but he is no imposing presence. In fact, he seems almost to stoop deferentially when he speaks. His boyish good looks belie his years, and while he claims to be shy, he speaks at length with depth and insight about his practice and the world.

Devon, in southwest England, is Shrigley’s home, a place he shares with his wife Rita and their beloved miniature schnauzer Inka. His main studio is in Brighton. He was born in 1968 in Macclesfield, Cheshire, but grew up in Leicestershire. He studied at the Leicester Polytechnic and later at the Glasgow School of Art, where he scored a 2:2 – the lowest possible pass mark – on his final degree show. “I’ve learned to let that go,” he says of what he deemed at the time a great failure. (He has previously jokingly said the markers had failed to recognise his genius.) Shrigley moved to Glasgow when he left England for art school, and only returned to England a few years ago.

“Scotland is a very special place for me,” he says. “In fact, being back in England I feel almost like an outsider again.” He offers over the table a Tunnocks Tea Cake, a Scots chocolate delicacy. “These things are absolute heaven.” Old habits die hard.

Shrigley’s father was an electrical engineer and his mother was a computer programmer. They encouraged his art from an early age.

“I was the kid that you could leave alone with a piece of paper and pen, and I could occupy myself for hours,” he says. “The challenge as a middle-aged man is to understand the joy you had when you were five years old. Things now get in the way of joy – art education, and the art world, and theory of art criticism and art history. It gets in the way of the vision you have, which is for me the same thing at 50 as it was when I was five.”

So does he only make art when he feels joy? Shrigley laughs.

“I would never get anything done if that was the case. I work five days a week, eight hours a day. And if I’m busy, I work weekends. It doesn’t mean you can’t expect to be joyful every day. Sometimes it’s a slog, and sometimes you just want to stay asleep. But I’m a professional, finally, so I have to do it. I’m fortunate.”

During lockdown, in Devon, his fame seemed to hit a new apex. He decided to created an image a day for a year. Lockdown Drawings comprised, in the end, 400 black-and-white ink-on-paper illustrations. The works had a psychologically darker element to them. A set of fingers flicking the V reads: “Bollocks to you and to everyone and to everything.” A hand holds a joint, with the tag line: “Chill out, please. You’re doing my head in.”

“I liked lockdown,” he says. “And I learned a lot. I have a home in the countryside and so I could hang out with my wife and my dog. I’m still married. That’s good. The dog’s healthy. That’s good.

“I am an introvert, which means the fact I couldn’t go to the pub made me quite happy. Being able to go around and see my one friend in the village and smoke weed in the back garden was great. At the time I was quite ashamed to say that, because many people were having a hard time. But for me, it was good.”

Observers have noted Shrigley’s work – introspective, ironic, subversive – was ahead of its time: his work seems always to have reflected a lockdown mindset.

“It’s very much the same strand of thinking. The work always has the same sort of slightly nihilistic darkly comic perspective,” he says. “But it’s difficult for me to see. It’s just my voice. Making a record of life through drawing has always been a good therapy. It makes me feel better about the world.”

So, is Shrigley an optimist or a pessimist? Glass half full or empty?

“I would say that you have a choice. You can be optimistic. And I choose to be optimistic,” he says. “Whether I appear that way to other people, I don’t really know. But I think that making art is always positive.”

-

There’s movement at the cloister next door, and it seems a good time to ask if Shrigley is a god-fearing man.

“Well, I am from that background. My dad’s an evangelical Christian and my mum’s from the Church of England; my sister is training to be a priest in New Zealand,” he says.

“I’m a sympathiser but I don’t practise any of that stuff.”

Shrigley has published a number of books, most notably a self-help book called Get Your Shit Together, but his latest project is different. It involved acquiring thousands of copies of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, pulping and republishing them as George Orwell’s 1984. The Pulped Fiction project began when the artist saw an advertisement from a charity store in Swansea, beseeching people not to donate the book, which they could not give away let alone sell. Shrigley gathered 6000 copies of Brown’s tome, destroyed them and created 1250 copies of 1984 (the book is out of copyright, meaning Orwell’s work is in the public domain), featuring his signature capitalised font on the front cover.

The artist also helped brand a beer at his local pub. It’s called Toad Licker, and a can of the ale emblazoned with the words “Something Weird” sits, conspicuously opened, on the table in his studio. “Basically all of my profits from the beer go to the church community project and the table tennis club, the community food project and their community group,” he says. “They’re very good neighbours. We give them a little bit back. ”

Giving back is the central tenet of a second Shrigley work coming to the NGV. The Melbourne Tennis Ball Exchange will open there in January. It is an antipodean riff on his Mayfair Tennis Ball Exchange, a work that features a wall of 8000 new tennis balls and which invites audiences to trade new for old. The show opened in 2021 at his gallerist Stephen Friedman’s Mayfair shopfront. The work was inspired by his dog.

“Inka is obsessed with tennis balls, but has a really weird relationship with them in that she never brings them back. She will give it to me if I shout. But usually we have two tennis balls. One, she goes and gets; one she brings halfway back, drops and then looks at something else. So it’s just this idea of exchange. Animals don’t have possessions. They just have status. Material objects are irrelevant.”

Shrigley does not have children, and has over the years “collaborated” many times with his dog on artworks. “Perhaps, because of that, I consider the dog’s point of view more than other dog owners do,” he says.

There is a subversive element, too, to the project, Shrigley says. “It was in a fancy gallery in Mayfair, which is all about selling very expensive things. And I was like, ‘What if we don’t sell anything, but exchange things, because that’s still a form of commerce?’,” he says.

The exchange will open at the NGV in the same week as the Australian Open tennis championship begins in Melbourne. “Wouldn’t it be great if Andy Murray won,” says Shrigley with a smile. “I really like him.”

Murray, similarly, is a Shrigley fan. He reportedly owns an original work or two, and the pair recently appeared together in an in-conversation event. Shrigley can’t confirm whether the Scots player will participate in the exchange. “He may have other things to concentrate on in Melbourne at that time,” he says. “We can always hope.”

-

Almost 40 years into his practice, and at the top of his game, does Shrigley finally feel accepted by the establishment? He thinks for a moment. “I’ve reached a point in my life where I realise it doesn’t really matter,” he says. “I’m happy.”

The artist is putting the final lettering on my arm. Above the glass is the word HALF; below it FULL. Earlier, I had almost knocked the tumbler of water with my elbow, and – after discussing drawing a dog and or a seagull – we had decided this was as good an omen as any. Shrigley, satisfied, sits back and inspects his handiwork. “Half full. I like it.” The papier mache thumb model for Really Good, sitting on a shelf in the corner of the room, seems to salute in approval.

“Am I a glass half-full or glass half-empty kind of guy? I’m not sure,” I tell Shrigley. As a professional cynic, optimism can be hard to guage. Is this drawing a symbol of dark irony or fanciful optimism? The artist smiles. Maybe it’s both.

I thank Shrigley for his time, and nod to the vicars, who wish me luck, as I head back out into the squall. My umbrella surrenders to the elements, and I spy a tattoo parlour on a corner, a Georgian vision in black. Refuge from the storm.

I open its huge door, and enquire loudly whether there are any Shrigley fans here. A young female tattooist gushes in response. Staff there have personally inked some of his designs on customers.

“He’s so great,” she says, as she inspects the fresh drawing on my arm. “Would you like it done now?”

Permanence.

Do I want a hastily drawn glass of water on my arm forever? Probably not. But, then, maybe I do. Irony, optimism, cynicism, hope, humour. It’s all there the more I look at it, and I hear myself saying “Yes” to my first tattoo.

I’m led downstairs into a small mirrored room. Louis – a lifelong Brighton local with a fear of flying and a disaffected chihuahua who sits quietly in the middle of the room – turns up the stereo. His favourite band, Insomnium, blares.

“Finnish melodic death metal,” he says, flashing a wild smile that I realise may actually be slightly too wild for my liking. “This song is called Weather the Storm.”

Of course it is. Weather the Storm. Accept the pissing rain. Pokey things. I would like to write on your walls with my crayons. The artwork: it never turns out the way you want.

Glass half full? Go on then.

The tattoo gun buzzes. Last chance to pike out.

The dog glances up from its bed below and holds my gaze.

Needle presses flesh.

Don’t move.

Tim Douglas travelled to Brighton with the assistance of the National Gallery of Victoria.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout