Whitlam, Fraser, the Queen and the Dismissal: the truth

A new book on the 1975 Dismissal raises important questions about everyone involved.

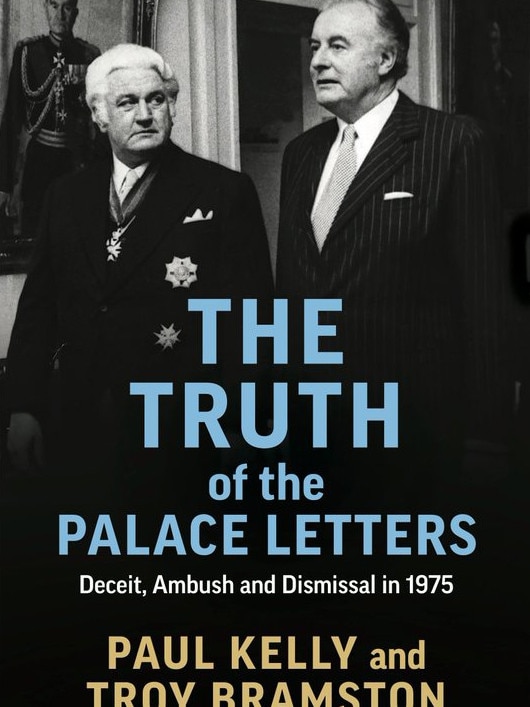

The Truth of the Palace Letters, a new book by senior journalists Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, shows that the gates of history are never closed, that it is always possible to find new perspectives on past events no matter how much coverage they have had.

The removal of the Whitlam government in 1975 and the events leading up to it are examined in the light of the so-called Palace letters, more than 1200 pages of material released by the Australian Archives earlier this year and centred on the correspondence between the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, and the Queen’s Private Secretary, Sir Martin Charteris.

On Kerr’s side, the frequency and length of these letters strongly suggest that the vice-regal role had gone to his head. The authors, each political correspondents at The Australian, have meticulously mined this and much other material to produce a graphic account of the most extraordinary time in Australian political history.

This book has a rich cast of villains from the drama of November 1975. It is important, however, to start with Malcolm Fraser who engineered this assault on the Australian political system by blocking the Budget in the Senate.

Fraser was one of the most unscrupulous characters in Australian political history and, as Paul Keating points out in the preface to the book, he was not prepared to wait the relatively short period to the next election, which the Liberals would certainly have won, given the self-destructive conduct over some years of a number of the Whitlam government’s ministers.

In later life Fraser became a darling of the politically correct class when he adopted some of their causes.

They seemed oblivious to his early career.

In his own bizarre memoirs the most unbelievable assertion was that, although he was minister for the army during the Vietnam period in the 1960s, he learned for the first time in 1995, when reading Robert McNamara’s own memoirs, that the US administration was involved in the coup that led to the deposing and assassination of the South Vietnamese prime minister, Ngo Dinh Diem, in 1963 – something that most schoolchildren would have known at the time.

The role of Sir Garfield Barwick in November 1975 was hardly surprising. He was implacably hostile to the government, not least because of the appointment of Lionel Murphy to the High Court and, although Chief Justice of the court, had no hesitation in stepping into the political arena and encouraging Kerr in his plans to remove the government.

More puzzling is the conduct of Sir Anthony Mason, as a judge of the High Court, who provided advice to Kerr for some months prior to November 11 and drafted a letter on November 9, which Kerr ultimately did not use, terminating the Prime Minister’s commission, for Kerr to hand to Whitlam.

On the afternoon of November 11, he was still advising Kerr as to how he should respond to Labor’s parliamentary response to the government’s removal. This was an extraordinary abuse of judicial office and remains almost inexplicable. It is noteworthy that Mason is never mentioned by Kerr in any of his letters to Charteris.

Then we come to the Governor-General himself who orchestrated the removal of the government, a removal that Fraser and his party had set in motion. The Palace Letters underline the extraordinary secrecy with which Kerr proceeded to ensure that nothing would go wrong with the plan that his side of the correspondence reveals him to have been clearly formulating.

This involved lulling Whitlam and some of his ministers into a false sense of security with an acting performance worthy of the stage.

This is not to deny that Kerr was in a difficult position but he was obliged to confront Whitlam with the possibility that an election might finally be necessary to resolve the impasse in the Senate.

This would not have been an attractive proposition, given Whitlam’s propensity for unpleasant behaviour, but, if Kerr had taken that course, he would have emerged from these events with his reputation enhanced instead of largely destroyed. If this had provoked his removal as Governor-General – a possible but very unlikely outcome – he would have become a noble victim rather than a foremost villain.

Instead, soon abandoned by those whom he had brought to power and seen as an embarrassment by the palace, he was allowed to resign before the end of his term and forced to spend most of his later years out of Australia in exile.

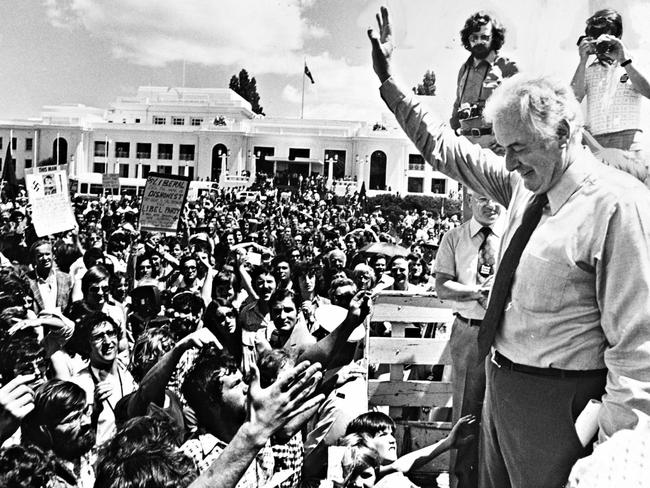

That leaves the Prime Minister, ostensibly the real victim in all of this.

But Fraser would not have had his manufactured excuse for blocking the Budget in the absence of the Loans Affair, an absurd and unsuccessful attempt to borrow large sums of money overseas in secret by a small group of ministers that included Whitlam himself.

Apart from the highly damaging publicity when the affair became public, one side effect was Kerr’s concern that he may have been involved in something illegal by signing some of the documents that authorised the loan negotiations. And what is one to make of Whitlam’s powers of observation and deduction when he saw Kerr every few days in the lead up to November 11 and noticed nothing unusual about his demeanour.

Hardly a rival to Sherlock Holmes here!

In addition to his concerns about the Loans Affair, which was not in fact illegal but otherwise indefensible, Kerr was almost certainly disturbed by Whitlam’s proposal that the banks should fund government salaries and debts until the Senate confrontation was resolved.

The banks obtained advice that raised serious doubts about the legality of the proposed arrangements and there is little doubt that these opinions were provided to Kerr before November 11, raising further concerns as to his own involvement in the government’s struggle to survive.

Whitlam’s proposal on November 11 for an election for half of the Senate triggered the removal of the government but, as the book points out, the prospects of such an election changing the complexion of the Senate and so affecting the blocking of the Budget were quite remote.

It is true that Kerr had carefully devised a plan for the dismissal of the government and would almost certainly have implemented it anyway within a short time but it was the futility of a half-Senate election that designated November 11 as the day for his decision.

One of the book’s avowed purposes is to absolve the Queen of any role in the removal of the government.

It certainly succeeds in that objective and makes the point that Charteris emphasised to Kerr that the use of the so-called reserve powers of the Governor-General, which extended to the dismissal of a government, were very much a last resort in any circumstances.

Nevertheless, it was certainly a curious situation in which the Queen and her advisers knew what was likely to happen in Canberra, if not exactly when, but no one in the Australian government had the same knowledge.

This is not to suggest that the Queen should have intervened in any way as the Australian Constitution makes it clear that the crisis could only be resolved in Canberra and not in London. But this in turn raises the question of what is the point in having the British monarch at the apex of Australia’s political system if he or she has no real role to play in that system.

Which leads to the next question – the subject of the failed referendum in 1999 – of whether the move to a republic should be revisited.

The referendum was lost because bloody-minded proponents of a popularly elected president preferred the status quo to the option of a president appointed by the federal parliament. But this position is now reversed. Many of those who originally supported the idea of a republic now prefer the status quo to the prospect of a president directly chosen by the electorate and so able to set himself or herself up as a rival to the prime minister.

As the book notes, the first task of the republican movement is to find a model that can reconcile these competing views. It is also a problem for the movement that some of its supporters want other major constitutional changes at the same time, such as a bill of rights or abolition of the states, and these unrealistic propositions only weaken the likelihood of obtaining the main objective.

Because the Senate still retains the power to block or reject a budget, it is theoretically possible that the events of November 1975 could re-occur, although for a number of reasons this seems unlikely. It is hard to imagine that any future chief justice would act as Barwick did or any High Court judge as Mason did.

And any future governor-general would certainly be given pause by the sad years that followed for Kerr after his decision to remove the government without warning. But, even if the great drama of November 1975 is never repeated, it will continue to provoke discussion and debate, as this new book will certainly do.

Michael Sexton’s books include Gough Whitlam: The Rise and Ruin of a Prime Minister.

Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston will discuss their book with political journalist Michelle Grattan at an event at Australian National University on November 12. Details: www.mup.com.au/events

On November 17, the authors will join the editor of The Australian, Michelle Gunn, for a free online event available to subscribers of The Australian. Details: www.theaustralianplus.com.au/events

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout