Which films earned a rare five stars from David Stratton?

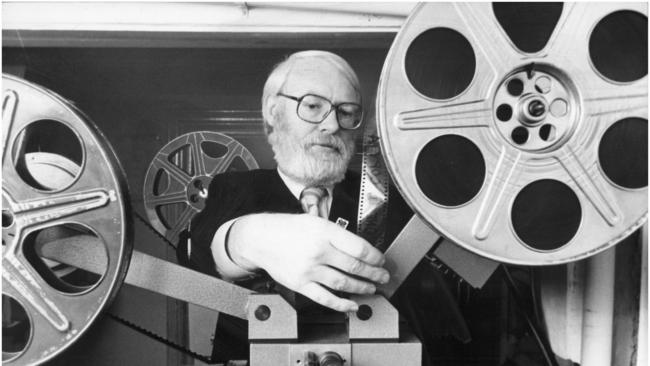

We look back over some of the films awarded a perfect score by the legendary film critic during his 33 years writing for The Weekend Australian.

We look back over some of the films awarded five stars by legendary film critic David Stratton during his 33 years writing for The Weekend Australian.

–

Apocalypse Now Redux (R)

Date reviewed: 10/11/2001

If Francis Ford Coppola had been able to shoot his epic Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now in northern Queensland, as he planned, it might have turned out very differently. In the mid 1970s, some of his collaborators scouted locations there for the proposed adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness. But the federal government in 1976 wasn’t sympathetic to Coppola’s anti-war project and, crucially, denied military co-operation. Instead, he filmed in The Philippines, which proved problematic and expensive.

The original 150-minute film was a qualified success; it had its share of unforgettable sequences — who can forget the dawn raid by Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) on a village, accompanied by the music of The Ride of the Valkyries? — but a strangely muted and unsatisfying conclusion. Over the years, Apocalypse Now has become, deservedly, a classic.

Now comes Apocalypse Now Redux, the eagerly awaited final version of the film, 53 minutes longer than the original. The result is a different experience. The bulk of the film is still there, of course, but the characters are fleshed out in more detail.

The film concerns the journey upriver of Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), sent to terminate with extreme prejudice rogue officer Kurtz (Marlon Brando) who has, it seems, been driven insane by his experiences and set himself up as a kind of tribal chieftain in the Cambodian hinterland. Willard travels upriver by boat, with a crew (Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Laurence Fishburne) unaware of his mission.

In Redux, a new sequence comes at the end of the raid on the village. Kilgore, a fanatical surfer, has agreed to help Willard only because one of his crew is a surfer of some renown; the sequence now ends with Willard and his crew stealing Kilgore’s surfboard and, later, hiding, while the furious officer hovers above in his chopper, howling abuse.

Also new is the forlorn sexual encounter with a bunch of stranded Playboy bunnies, trapped in an abandoned medical centre.

Then there’s the sequence in a remote plantation, where Willard and his men are welcomed by a Frenchman (Christian Marquand) who is able to place the conflict in the context of French colonial experiences in Indo-China and where Willard experiences a dreamlike romantic interlude with the beautiful Aurore Clement.

Perhaps best of all is an extra scene with Brando. In the previous version, all his scenes took place in darkness and shadow; now Kurtz is seen in daylight, surrounded by children — he assumes the mantle of a teacher as he reads an authentic article about the war from Time Magazine.

The new scenes, seamlessly integrated, result in a three-hour, 20-minute film, but the experience is considerably enhanced. And watching it as a new war is being fought by Americans imbues Coppola’s epic with ever greater resonance. Will the sons of the Vietnam warriors face similar demons hunting down the Taliban?

–

The Barbarian Invasions (Les invasions barbares) (MA)

Date reviewed: 10/04/2004

About 18 years ago, a French-Canadian film titled The Decline of the American Empire (Le Declin de l’empire americain) enjoyed a comparatively wide release. It was the breakthrough for Quebec director Denys Arcand, a brilliant satirist and wit who had been making probing films since the early 1960s about life in Canada’s most idiosyncratic province.

Despite the ironically epic title, Decline is an intimate comedy about a group of history professors who get together with their lovers (only one of them is married) for a dinner party rich in acid conversation about the battle of the sexes and the human condition generally. The leader of the group is Remy (Remy Girard), an ebullient, caustic left-winger married to Louise (Dorothee Berryman), though making little secret of the fact that he isn’t faithful to her. There is also the philandering Pierre (Pierre Curzi), the gay Claude (Yves Jacques) and Alain (Daniel Briere), the youngest. For 100 minutes distinguished by sparkling dialogue and engaging performances, the film examines these characters with insight and affection.

Arcand has only made one significant film since Decline, and that was the brilliant Jesus of Montreal (1989), but last year he produced a sequel to the earlier film, which he graced with an equally epic title, The Barbarian Invasions. An instant success in Quebec, it won two awards in Cannes and, a few weeks ago, an Oscar for best foreign language film — all accolades thoroughly deserved.

In the intervening years, Remy and Louise have finally divorced (really no surprise). But when Remy discovers he is suffering from terminal cancer, Louise is quick to make contact with their children — who are, as it happens, far from home. Their daughter is sailing on a yacht in the Pacific and their yuppie son Sebastian (played by a locally popular stand-up comedian, Stephane Rousseau) has been making a fortune in the London futures market and has a glam French fiancee, Gaelle (Marina Hands). Remy and his son haven’t spoken for a number of years — they couldn’t be more different, really, since Remy has always espoused socialism and Stephane seems set to make a million before he’s 40. But Stephane and Gaelle catch a plane to Montreal and soon Stephane is using all his capitalistic wiles to extract his ailing father from the horrors of an overcrowded public hospital (scenes that are very funny and painful).

Louise also summons all Remy’s former friends (played by the same actors as before) and a few former lovers. But what could have been a happy reunion is, of course, marred by the sad reason for the get-together. Though I found the fact that I still have the most vivid memories of The Decline of the American Empire added to my enjoyment of The Barbarian Invasions, I’m sure the new film can be enjoyed almost as much if you have no knowledge of its predecessor.

I have the impression that French-Canadians consider themselves a pretty unique bunch and yet, while watching Arcand’s film, I couldn’t help thinking that they share many more experiences with Australians than they do with Americans. Canadians have always been very aware of the fact that they share a border with their all-powerful neighbour and, as a result, they have a love-hate relationship with the Yanks even more intense than our own. This relationship gives the film a powerful subtext but Australian audiences will also instantly recognise the film’s other main concerns — an underfunded hospital system in which patients are forced to sleep in corridors, fear of terrorism, the decline in education standards and, yes, US domination.

The concerns are recognisable and so are the characters. These are flesh-and-blood human beings, sometimes amusing, sometimes afraid, sometimes wracked with grief. Arcand’s intelligent, witty, delicate film is a constant joy and for once the academy got it right — this foreign language film richly deserved its Oscar.

–

Brokeback Mountain (M)

Date reviewed: 28/01/2006

Ang Lee’s new film, which is quite simply one of the finest love stories brought to the screen, has been described as a movie about gay cowboys. This is despite the fact that the protagonists of this achingly sad story, Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) and Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) don’t see themselves that way.

``You know I ain’t queer,’’ mutters Ennis, to which Jack replies, ``Me neither.’’

There’s always been an unstated gay element in Hollywood westerns. Women play marginal roles in most of them — they’re either virginal schoolteachers or whores — unless they’re the gun-totin’ Annie Oakley type of female, in which case they’re on the butch side.

The best westerns have been about friendship between men: John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Red River, Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the members of The Wild Bunch. In the latter film, the look Ernest Borgnine gives William Holden just before they set out for their final gunfight speaks volumes. Andy Warhol tapped into this subtext for his 1968 film Lonesome Cowboys, which could be an alternative title to Brokeback Mountain.

Ennis and Jack meet in Wyoming in 1963 when they’re given the task of guarding a flock of sheep on Brokeback Mountain (so they’re not cowboys but sheepmen. Odd, isn’t it, that the ``boy’’ was applied to herders of cattle and ``men’’ to herders of sheep).

Ennis was orphaned when his parents’ car failed to take the only bend on a 70km stretch of road; Jack, a Texan, feels uncomfortable with his father and has tried rodeoing with mixed success. Their summer on Brokeback — lonely, isolated, frustrating — leads, one cold night, to the sharing of a tent and some drunken, unanticipated sex. It’s an event that changes both their lives.

The pristine screenplay by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana is faithful to Annie Proulx’s short story but expands 30 pages into a two-hour film. It never feels overextended.

Director Lee has packed a great amount into the running time. The years pass, the men marry, have children, live their lives — yet manage to meet now and again for what they euphemistically call fishing trips. It would have been easy for the film-makers to demonise these men who cheat on their wives or, alternatively, to turn the wives into hostile characters, inhibiting their men.

Lee does neither. He allows us to understand the friendship and love that Ennis and Jack have for one another and he also allows us to understand how their behaviour affects their women, who are beautifully played by Michelle Williams and Anne Hathaway.

The remarkably versatile Lee, whose past work includes Sense and Sensibility, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, The Ice Storm and the comic book adaptation Hulk, never puts a foot wrong. His collaboration with Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto results in breathtaking landscapes and cloud formations and scenes of shared intimacy; the plaintive guitar-led music score by Gustavo Santaolalla is equally evocative, and the songs that accompany the final credits — He Was a Friend of Mine by Bob Dylan, sung by Willie Nelson, and Rufus Wainwright’s Maker Makes — will leave a tear in your eye. The last two sequences of the film are two of the best scenes in American cinema in many years and, indeed, this may be the love story of its generation, to rival classics such as Gone with the Wind.

Ledger and Gyllenhaal deserve nothing but praise for their brave, sensitive portrayals of troubled souls, ordinary guys who discover love in a totally unexpected place, but who are unable to derive lasting happiness from what for them is an unforgettable moment.

Not everyone admires the film, of course. In America, some people have been outraged and a review by the Christian Film & Television Commission, which calls itself ``a ministry dedicated to redeeming the values of the mass media according to biblical principles’’, called the film ``twisted, laughable, frustrating and boring neo-Marxist homosexual propaganda’’. Make of that what you will.

–

No Country for Old Men (MA15+)

Date reviewed: 22/12/2007

`This country’s hard on people,’’ muses an old Texan, a former lawman, reflecting on his life. His son Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) is the third generation of sheriffs in this part of the west Texas-Mexico border country. With its timeless vistas and rock formations, this would be beautiful country if not for the abandoned and rusting cars that litter it, or for the ugly, violent men who inhabit it. Ed Tom reckons the decline began when young people stopped respecting their elders, when they stopped saying ``sir’’ and ``madam’’. But he acknowledges that ``you can’t stop what’s coming’’.

Ed Tom is the moral centre in this adaptation by Joel and Ethan Coen of Cormac McCarthy’s chilling novel No Country for Old Men. It is an extremely faithful version of the book that retains most of McCarthy’s language as well as being a close-to-perfect visualisation of his text. And lovers of the book will be pleased to hear that the Coens have not compromised the ending. They’ve turned a fine book into a great film, the best released here in 2007.

Basically, the theme is a simple one, familiar from many a past thriller. Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) is an ordinary guy, a Texas everyman who lives with his wife, Carla Jean (played impeccably by Scottish actor Kelly Macdonald) in a small house, nothing fancy. One night, out hunting deer, he stumbles on a massacre, the site of a gun battle between, presumably, rival drug gangs.

Among the bullet-riddled bodies is a suitcase containing $2 million. Llewelyn takes the money and this proves to be a very, very serious mistake. Not only is the sheriff after him but, far more threateningly, so is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a long-haired hitman who lives by his own skewed moral code and who, we discover at the outset, is implacably evil. Chigurh is unrelenting in his dealings with those unfortunate enough to cross his path, although he will on occasion allow a coin to be tossed to decide the fate of his latest victim.

As an exercise in suspense, No Country for Old Men has few peers. A sequence in which Llewelyn, in a hotel room, senses that his nemesis is outside the door is nerve-racking for the audience as well as for the protagonist. But the Coens, making their best film since Fargo (and there are similarities in the combination of ruthlessness and dark, dark humour), have created more than just a thriller: it probably sounds precious to suggest it, but the film is really about the state of the world, a metaphor for the way Western civilisation is heading at the beginning of the 21st century.

The central performances, including Woody Harrelson as an overconfident intermediary working for the owner of the missing money, are beyond praise, but what further distinguishes an already major film is the impeccable casting of the most minor characters: an assortment of hotel clerks, petrol station attendants, storekeepers and others (one of them played by an actor who reminded me a lot of Marjorie Main) add fresh dimension to the drama.

The highest praise is due to British cinematographer Roger Deakins (who also photographed Andrew Dominik’s superb The Assassination of Jesse James). His feel for this parched, dangerous countryside and the towns and small cities that dot the landscape makes an important contribution to the success of a remarkable film.

–

Samson and Delilah (MA15+)

Date reviewed: 02/05/2009

The often troubled Australian film industry, despite the occasional unwarranted attack by newspaper columnists, looks to be heading for a vintage year in 2009, with several soon-to-be-released films promising a great deal. For the moment, it’s a pleasure to welcome one of the films selected to represent Australia in Cannes this month, Samson and Delilah, which was written, photographed and directed by the talented Aboriginal filmmaker Warwick Thornton, and is a triumph for all concerned. This movie may well be heralded as something close to a masterpiece. Whether it will attract audiences to the box office, goodness knows, but box office results are not the mark of a great film; the most egregious Hollywood trash regularly finds its way to the top of the box office charts in this country and probably always will.

Thornton’s beautiful, tender, heartbreaking film explores a couple of teenagers who live in a tiny, isolated, community somewhere near Alice Springs, the sort of place white Australians never visit and can hardly imagine. Samson (Rowan McNamara) has no family. He lives in a miserable shack, sleeps in his clothes, and sniffs petrol or glue, whichever is more accessible. Occasionally, he fools around in an abandoned wheelchair. Outside his window, three men rehearse regularly with musical instruments and Samson clearly would like to join them, but they won’t let him, and one of them beats him up for no valid reason. Delilah (Marissa Gibson) lives with her aged and disabled grandmother (played by Gibson’s own grandmother, Mitjili Gibson), and helps her as painstakingly she creates the works of art she sells for a pittance to a middle man and which, we later discover, are retailed for thousands of dollars to tourists in Alice. The young people meet, but don’t talk to one another, at the general store.

Samson’s courtship of Delilah reflects his inarticulateness. He tries to get her to notice him by throwing a stone at her, or by leaving a message in graffiti. She is well aware of his presence, but when he boldly moves his mattress to her place, she removes it.

Her lack of interest isn’t shared by her grandmother, who seems, in her enigmatic way, to encourage the young couple.

The film follows the fortunes of the pair when they leave the settlement and try to find a more meaningful life in Alice, though it appears the best they can hope for there is to squat under a road bridge across the Todd River and survive by shoplifting. They are befriended by a homeless alcoholic, played by the director’s brother, Scott Thornton, who is strange and a little scary but who proves to be less scary than some of the other characters they encounter.

On one level, Samson and Delilah is a desperately sad film. It is heartbreaking to watch the stunted lives of these young Australians unfold in an environment where the future seems so terribly bleak. Yet the film is optimistic: Samson and (especially) Delilah are resilient, and even in the most confronting circumstances the film is suffused with a bleak sense of humour.

One of the most remarkable attributes of Samson and Delilah is the acting. Presumably both inexperienced, Gibson and McNamara give unforgettable portrayals that almost convince you they’re not acting at all but just being. Another impressive element is that Thornton is able to tell his story with a minimal use of dialogue. Samson speaks only one line in the entire film, and Delilah not much more. It’s a remarkably sophisticated achievement to unfold a story like this one almost entirely in visual terms. As a result there is a very strong sense of place, both in the dusty, almost deserted community and in the strangely hostile city of Alice, where tourists visibly shudder when a dishevelled Delilah attempts to sell them some of her paintings.

Thornton photographs the film with a handheld camera, but he’s talented enough not to indulge in the gratuitous queasiness affected by some of his more vaunted peers. The film’s music score, part of it also the work of the director, is of unusual importance to the success of the whole.

Anyone who cares about Australian cinema should see this film. I’d go further and suggest that anyone who cares about Australia should see it. Samson and Delilah is, quite simply, one of the finest films ever made in this country.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout